John Cage famously said that musicians in the post-war world had to learn from visual artists, while poet Frank O’Hara called himself the balayeur des artistes, or sweeper-up after artists. What is it that fascinates artists about those in other fields, drawing them across the lines, to listen, to watch and sometimes to engage in the cross-pollination of working together? Artists see something of themselves and something different in these other artists; they realise there is a unique opportunity there for expansion.

Sometimes groups of artists in different fields gather together to live and work. Particular constellations that compel us by their hybridity can clarify aspects of the individual artists’ personalities and needs. Interactions can take the form of collaborations, published criticism, attempts to promote one another’s work, or simply learning from conversation and example. The modern idea of hybridity goes back at least as far as Baudelaire, who was a classic example of the poet-critic. Since his time, his has been a standard to live up to.

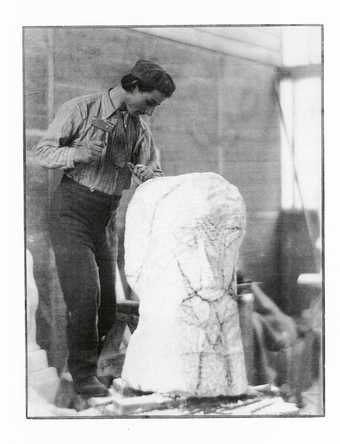

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska carving Hieratic Head of Ezra Pound c.1914

Photo: Walter Benington. Courtesy Benington Archive

In fact, this has been a tradition that has its roots in Paris. Apollinaire, Picasso and Gertrude Stein were at the centre of a group that became immortal as much for its interactions – including an alleged theft of the Mona Lisa from the Louvre, for which Apollinaire and Picasso were briefly arrested – as for each artist’s towering individual achievements. The French tradition included theatre pieces, such as Parade, a joint venture by Picasso, Cocteau, Satie, Massine and Diaghilev, as well as many collaborative books and films. For the Surrealists, crossing over aesthetically was an embodiment of their belief in crossing over psychologically – both involve relinquishing conscious control.

The School of Paris gave way to the New York School, and while the first generation New York painters were not known for collaborations, they were hugely influential and set the tone for other artists, as Cage noted. The New York School poets pursued an informality in their compositions influenced by the Abstract Expressionist painters; they were equally informed by French writers and in some ways can be seen as an offshoot of the French tradition. The Baudelairean poet-critic returned in the poets Frank O’Hara, John Ashbery and James Schuyler, and collaboration was a life-blood for their friend Kenneth Koch, artists Jim Dine, Alex Katz, Larry Rivers and others.

In five lesser-known examples that I include here, we can see that encounters between poetry and the visual arts are, if not the rule, then definitely not the exception. Through their work we may get hints of what brought these artists together in the first place. I have been able to detect the following arc: classic modernists drew on each other’s energies to reinforce their own monolithic ambitions; post-war artists were much more eclectic in choices of friends, styles and media; artists working today seem to have retreated to the relatively safe domain of the book, though imbuing it with relentlessly experimental fantasy.

In the years leading up to the First World War, Blaise Cendrars had the idea of writing a big poem, and he succeeded, with La Prose du Transsibérien et de la petite Jehanne de France. Similar to Apollinaire’s Cubist poems, in which punctuation is jettisoned and ideas allowed to flow backwards and forwards ambiguously in their syntactical settings, La Prose is a tour de force of energetic motion – the train ride from Europe to Asia, with its wilful disruptions of time and place, forging a powerful metaphor for the artist’s desire to be free from bourgeois limitations. With its contemporary language and images and freedom from literary reference, Cendrars’s poetry, it can be argued, is even more modern than Apollinaire’s. He believed La Prose would find its appropriate home in a visual setting, and therefore contacted Sonia Delaunay, a Russian émigré living in Paris, whose work had an appropriate openness. Delaunay later recalled her reaction to the poet’s idea: ‘I proposed that we create a book that, unfolded, would be two metres high. I sought inspiration in the text for colour harmonies that would parallel the poem’s unfolding. We chose characters of different fonts and sizes, a revolutionary procedure at the time.’ Together they produced the printed edition of the poem with Delaunay’s pochoir counterpart. The publishers (Les Hommes nouveaux, a journal and press founded by Cendrars and Emile Szytta) called it the first livre simultané, meaning one saw the whole thing at a glance, like a painting or billboard, a comparison Cendrars himself underscored. La Prose was published in 1913 and had the desired result. Presented in Paris, Berlin, London, New York, Moscow and St Petersburg, it brought Cendrars the acclaim he desired. As the critic Marjorie Perloff notes: ‘It became not only a poem but an event, a happening.’

The choices artists make are revealing. Why did Pound in 1908, at the age of 23, move from the US to London? He had a masters degree in romance philology and had been teaching at Wabash College in Indiana. Dead broke, he barely supported himself as a writer. Clearly, he had a strong desire to be around other artists, and visual artists played an important role in shaping his aesthetic. Pound may have seen in the visual arts a more public level of success than that achieved by most poets. Like Cendrars, he wanted to become more visible. In London, he met artists he thought were world-class, and enlisted them in his quest to create history. The energy of the Italian Futurists exerted great influence on Pound and his new cohorts, painter Wyndham Lewis and sculptor Henri Gaudier-Brzeska. A movement would be helpful. Trying to get away from Symbolism, which Pound found too flowery, not concrete enough, he helped to form the Imagist literary movement, beginning in 1912. Like Cendrars and Delaunay, he wanted images that could be perceived at a glance. As he wrote: ‘ “Image” is that which presents an intellectual and emotional complex in an instant of time.’ In 1913, a year after the first Futurist exhibition in London, Pound coined the term Vorticism for the work Wyndham Lewis was making – and later organised Vorticist exhibitions in London (1915) and New York (1917). The vehicle would be Lewis’s journal Blast, which Pound helped to edit. The First World War interrupted Blast’s publication, but Pound continued his active role. Reading his and Lewis’s letters to one another, one can follow Pound’s efforts to sell Lewis’s works to the American collector John Quinn and to get Lewis’s novel Tarr published. Their correspondence is frequent, businesslike and also intimate, dealing as much with the reception of their aesthetic stances as with prospects for publication or sales.

Gaudier-Brzeska was a dynamic figure in Pound’s circle, writing a Vorticist manifesto and producing an exuberant body of sculpture and drawing. His most ambitious work is the Hieratic Head of Ezra Pound 1914, made from a piece of marble Pound procured for him, in which the simplified shapes of the poet’s brow and features hark back to earlier depictions of gods. The influence and desire work both ways: the poet emulated artists, and the artists were inspired by the poet. After Gaudier-Brzeska was killed in action in 1915, Pound not only acted as his executor, but also composed a memoir of his friend.

Pound’s influence was enormous, and three young poets in São Paulo, Brazil, in the early 1950s, took his example in a particular direction: they became the inventors of Concrete Poetry. One of Pound’s discoveries had been his interpretation of the Chinese ideogram as a vehicle capable of instant poetic expression. Another was his division of poetry into logopoeia, melopeoia and phanopoeia, roughly translatable as sense, music and image. Augusto de Campos, Haroldo de Campos and Décio Pignatari took these cues, creating a body of work that continues to resonate today in the practice of many Brazilian and American poets. The name they gave to what they did – Concrete Poetry – was adopted in Europe and the United States as a term that could encompass work by both poets and visual artists that had a condensed literary and visual impact. Significantly, they were in contact with contemporary Brazilian artists, such as Hélio Oiticica, who were experimenting with similar ideas. Augusto de Campos has spoken of his work as a poetry of refusals, of limitations, similar to the limitations placed on their art by Brazilian Concrete artists of the 1950s. First published in 1958 in the journal Noigandres, the Pilot Plan For Concrete Poetry makes the following claims: ‘Concrete poetry takes account of graphic space as a structural agent… in the visual arts (spatial by definition) time intervenes (Mondrian and his Boogie Woogie series, Max Bill, Albers and perceptive ambiguity, concrete art in general).’ Interestingly, they conclude by calling their work ‘absolute realism’, in contrast to an art of expression. The form should ideally be identical to the content.

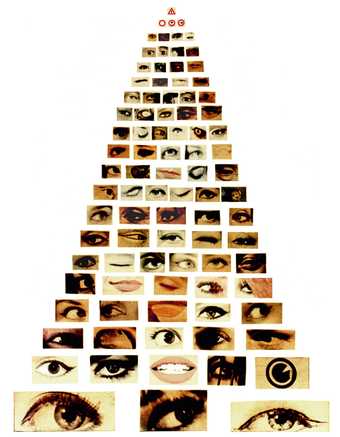

Augusto de Campos went on to produce ‘Popcrete Poems’, as he calls them, in which no words at all are used, but the images are so strictly chosen and sequenced that they function like letters or words, or, in fact, like modern ideograms. In other visual poems, he thickly layers text, sometimes in closely related colours, making it difficult to decipher the meanings. The Brazilian Concrete poets reflect a decidedly urban experience. Like Cendrars and Delaunay and the Imagist Pound, they often create works that can be seen at a glance and have the communicative power of billboards. Most of the time, when poets and visual artists are able to be in close proximity, it is because they have chosen to live in urban centres. Sometimes they find more rural settings in which to meet. Black Mountain College in North Carolina became one such centre from the 1930s through the 1950s. The experimental institution made the arts central to the teaching; there were collaborative theatre performances, including the first ‘happening’, led by Cage and Merce Cunningham. There was also an emphasis on book publication and joint projects involving artists and poets. The poet Charles Olson, Black Mountain’s last rector, forced poets to look at visual art and artists to read poetry. Cy Twombly, who studied at Black Mountain, asked Olson to write a preface for an exhibition he had in 1952. Olson recognised Twombly’s emerging talent; he grappled with the work, final blurting: ‘The dug up stone figures, the thrown down glyphs, the old sorrels in sheep dirt in caves, the flaking iron – there are his paintings.’ Olson got poet Robert Creeley, then living in Majorca, to edit the Black Mountain Review, in which poets commented on artists’ work. The magazine became highly influential in the poetry world, giving rise to the Black Mountain School of Poetry.

Through Pound, Creeley had met the French artist René Laubies, who first translated Pound into French. Creeley collaborated with Laubies and became a life-long devotee of visual art and artists, engaging in many collaborations. Unlike Pound, however, his choices of artistic partners ranged far and wide, including figurative as well as abstract artists, the fugitive as well as the fundamental. Creeley has written of his early days: ‘Possibly I hadn’t as yet realised that a number of American painters had already made the shift I was myself so anxious to accomplish, that they had, in fact, already begun to move away from the insistently pictorial… to a manifest directly of the energy inherent in the materials.’ In New York, he gravitated to the famed Cedar Tavern, where the painters congregated. As Creeley noted: ‘Possibly the attraction the artists had for people like myself… has to do with that lovely, usefully uncluttered directness of perception and act we found in so many of them. I sat for hours on end listening to Franz Kline… fascinated by literally all that he had to say.’

While Creeley admired the painters’ directness, his poems do not reveal an obviously visual debt to the painters. Charles Olson did hope to open for poetry a psychological immediacy predicated on a visual impact derived from that of modern visual artists. His influential essay, Projective Verse, has as one of its main principles the conception of the page as a ground. Mallarmé had much earlier, in his poem Un coup de dés jamais n’abolira le hasard, opened up the poetic page in terms of word placement and typography; Olson added the imperative that poetic creation take place on the page, much as the Abstract Expressionists’ creation took place on the canvas. He also proposed that the visual layout of a poem reflect the breathing and rests desired by the writer.

Creeley went on to maintain important ties with artists; his collaborations with around 30 of them were on view in the 1999 exhibition ‘In Company: Robert Creeley’s Collaborations’. Among those he worked with were Georg Baselitz, Francesco Clemente, Jim Dine, Bobbie Louise Hawkins, Alex Katz, R B Kitaj, Marisol, Susan Rothenberg and Robert Therrien. Creeley embraced the arts, particularly visual arts and music, connecting to many others he saw as trying to break from aesthetic and social restrictions he felt straitjacketed by in the 1950s, resulting in an everexpanding world of fellow-travellers he defined as an all-important “company”.

In the late 1950s to the late 1960s, Wallace Berman found his own company, much of it overlapping with Creeley’s. Berman would be considered a fugitive artist, eschewing the path of gallery and museum exhibitions of his work and laying much emphasis on art as a significant factor in lived relationships. Like Creeley’s, Berman’s company was diverse, a shifting world of poets, artists and musicians on the West Coast of the United States, moving between Los Angeles and San Francisco. Within that world, Berman was central, attracting the likes of William Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg, Dennis Hopper, Walter Hopps, Philip Lamantia, Henry Miller, David Meltzer, Dean Stockwell and John Wieners, and lesser-known people, some of them cult figures or drifters who burned out young, others, such as Bruce Conner, Jack Smith, or Jess, eccentric talents who have carved out places in art history. Berman made his voice heard primarily through his publication Semina (1955–64): sheafs of poems and images he printed himself and mailed out to a select audience (you could not subscribe or buy it anywhere). Hybridity was prized by Berman’s circle. There was the feeling that an artistic statement could be made in whatever medium the artist chose – literary, visual, musical, cinematographic.

Augusto de Campo

Eye for Eye 1964

Popcrete poem (collage on paper)

Courtesy Vincent Katz © Augusto de Campo

Today’s interactions between poets and visual artists take place less in the amorphous space of personal relationships, as they did with the Semina gang, and more often within the specified confines of a book. Often, poet and artist do not even know each other before agreeing to share space between the covers. A good example of this kind of action is French publisher Gervais Jassaud, who has been making small editions of books as Collectif Génération since 1969, often working with hybrid figures. His publications begin with a text by a contemporary author, many times a poet. Jassaud then ponders an armature that can appropriately enfold the text, with a hand-made design by a visual artist. Each project has its own solutions, with specific ways of opening and folding and display of text. He will often create several versions of a book – the same words embellished by different artists. Poet and critic Barry Schwabsky, whose poem Hidden Figure was published by Jassaud with work by Jessica Stockholder and, separately, with art by Katharina Grosse, has noted: ‘Collaboration depends on a complicity that goes well beyond the sympathy that a critic may have for a given artist’s work.’ Schwabsky’s complicity is far from Pound’s desire to find a partner with whom to do battle against the world; it is also distinct from Creeley’s and Berman’s wide-ranging personae. Schwabsky, in fact, did not know Stockholder before their book project began.

The idea that one person can control the means of production and distribution brings Jassaud’s projects close to the way poets think and work. After all, most poetry is published by poet-run small presses. Ruth Lingen, who has made artists’ books since the 1970s, sometimes using texts by poets, works in a similar fashion. Her books make themselves felt as physical objects: written, hand-set, designed, printed and bound by Lingen. She has also worked with Stockholder on a book collaboration with a poet: Led Almost By My Tie, with text by Jeremy Sigler. The mesmerising variety of textures and materials on which the poem is printed is as important to the experience of the publication as the poet’s words.

Jassaud and Lingen are creating venues where poets and visual artists can come face to face. These share something with Berman’s Semina, in that by their nature they have a limited audience, yet the exclamatory force of their materials and presentation ensures their impact will be felt repeatedly for years to come. Only time will tell how significant today’s reinvention of the book will be. Like John Cage and the New York School poets, today’s poets take life-force from the liquids and solids of works of art. Unlike Cendrars and Pound, they do not seek the visual arts as vehicles to greater success. Rather, they find in visual artists a common desire to emulate an art form other than their own. That desire to come together is powerful because it works both ways, and here we are able to learn, in a way we could not from earlier artists, what the similarities are between poetry and the visual arts.