In 1980 Richard Long exhibited at the newly opened Anthony d’Offay Gallery in Dering Street, London. The show was mixed-media: maps and photographs recorded a Water Circle Walk made between four lochs in the Scottish Highlands; terse text notes detailed Two Straight Twelve Mile Walks on Dartmoor; and across the floor of the gallery stretched Somerset Willow Line, hundreds of barkless willow batons laid out in the form of a section of path, 16½ metres long and two metres wide. An allusion, in part, to the Sweet Track – the causeway of bound coppice poles that was built around 3800 BC in order to give safe passage across the swampy Somerset Levels.

Richard Long

A Night of Rain Sleeping Place An 8 Day Mountain Walk in Sobaeksan Korea Spring 1993

Courtesy Kunstverein Hannover © the artist

Unexpectedly, the d’Offay show was accompanied by a ‘Statement’ from Long. Unexpectedly – because Long had previously kept silent on the subject of his own work, preferring to exhibit it unglossed. Printed at the Curwen Press, it appeared on a single sheet of card, folded into three panels. Its title was ‘Five, six, pick up sticks, seven, eight, lay them straight’, and the text consisted of 44 sentences, laid out on the page almost as the stanzas of a poem. The simplicity and repetitions of his language (as seen in the fragments below), combined with the mise en page, gave the document a peculiar atmosphere: part Ten Commandments, part nursery rhyme –

I like the simplicity of walking,

the simplicity of stones.

I like common means given

the simple twist of art.

I choose lines and circles because they do the job.

My art is about working in the wide world,

wherever, on the surface of the earth.

My work is not urban, nor is it romantic.

It is the laying down of modern ideas

in the only practical places to take them.

You might be able to hear the rasp of annoyance in that last section. For Long had been provoked to issue his statement out of irritation – irritation at the persistent mischaracterisation of his work as ‘romantic’, and irritation at finding himself repeatedly placed in a tradition of reverie- minded walker-philosophers that started with Rousseau and marched through Wordsworth, Coleridge, Borrow and Thoreau. This was an attempt to clarify his methods and his ambitions.

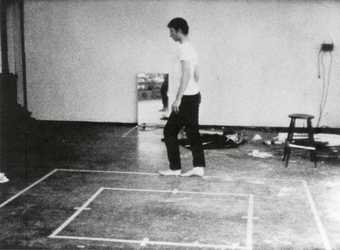

Richard Long

Walking Man and Plaster Path (at the West of England College of Art, Bristol) 1965

Image courtesy the artist

Long’s impatience seems to me quite understandable: romantic walking is so clearly a false genealogy for his art. The British version of this tradition is filled with pedestrians (William Hazlitt, Robert Louis Stevenson, Edward Thomas) who wish to stride back into a true sense of themselves. They foot forwards into the metaphysical wind of the world, letting it scour away the sour accretions of life – and they end their walks stripped back to their ideal natures. By contrast, American romantic roadsters (Henry David Thoreau, Ralph Waldo Emerson, John Muir) are more anticipatory: they imagine the walk as a way to find a new self, rather than to retrieve a lost one. British walkers recover, American walkers discover – and both traditions celebrate a self-consciousness on the part of the walker. They cherish the walker as thinker, and the walker as talker.

Either way, these walkers have very little in common with Long, who has always been far less interested in reflection than in motion, and less in mind than in body. His art practises, in fact, an almost immodest discretion with regard to the ego. The marks he has left behind in landscapes – rock-rows, snow-drawings, trails of crushed grass, circles of slate-blades – appear to be the scrupulously anonymised traces of an unspecific human body moving through space and time. That said, to describe his work as egoless isn’t to declare it devoid of personal content. And one of the most intriguing aspects of his art is how subtly it registers and re-expresses aspects of his childhood. Michael Craig-Martin, reviewing the d’Offay show for the Burlington Magazine, noticed this: ‘The art is rooted in his home territory and his childhood experience.’ Long later confirmed Craig-Martin’s intuition. ‘I feel I carry my childhood with me in lots of aspects of my work’, he remarked. ‘Why stop skimming stones when you grow up?’

Richard Long standing in the viewing place of 'England 1967' at Ashton Park, Bristol 1967

Photo: Martin Long

Why indeed? It’s a lovely question – innocently seen and innocently phrased. And Long has never stopped skimming stones, artistically speaking. His hundreds of circles – made around the world in stone, sand, wood, grass and footprints – can be imagined as the ripples of these skimmed stones. To my mind, his work is best understood as a set of persistently childish acts: the outcomes of a brilliantly unadulterated being-in-the-world. The word kindergarten was coined in 1840 by the German educationalist Friedrich Froebel (1782–1852). Kindergarten, literally ‘a children’s garden: a school or space for early learning. Froebel (less remembered now than Maria Montessori or Rudolf Steiner, for he didn’t lend his name to his method) wanted to create an environment in which children could be childish in the best sense of that word. Banished from his kindergartens was the Gradgrindian sense of the infant as a vessel to be filled with facts. Instead, he fostered an ideal of the child as micronaut – an explorer of the world’s textures, laws and frontiers, who should be left to make his or her own discoveries through unstructured play. Froebel wanted children to ‘reach out and take the world by the hand, and palpate its natural materials and laws’, as Marina Warner observes in a fine essay on play, ‘to discover gravity and grace, pliancy and rigidity, to sense harmonies and experience limits’.

Richard Long (standing left in boat) crossing the River Avon on the Pill Ferry in March 1969

Courtesy the artist. Photo: Denise Johnston

A nature-lover and walker from an early age, Froebel had a passion for the patterns of phenomena, and in particular for what he called ‘the deeper lying unity of natural objects’. It was for this reason that the early Froebelian kindergartens had few figurative toys. Instead of trains, dolls and knights, there were wooden cubes and spheres, coloured squares and circles, pebbles, shells and pick-up-sticks. Children spent their days singing songs and playing games, arranging the pebbles in spirals and circles, balancing blocks and picking up sticks. This open play was, as Froebel imagined it, the means by which ‘the child became aware of itself, and its place within the universe’.

Long is a childish artist in the Froebelian sense, and the wild world is his kindergarten. When Clarrie Wallis, curator of the new Tate exhibition, observes that his work is about his ‘own physical engagement, exploring the order of the universe and nature’s elemental forces… about measuring the world against ourselves’, she could be describing the Froebelian method. For more than 40 years Long has been using his moving body to explore limits, sense harmonies and apprehend balance and scale. His materials and his vocabulary have always been uncomplicated and childish. ‘I am content with the vocabulary of universal and common means,’ he wrote quietly in 1982, ‘walking, placing, stones, sticks, water, circles, lines, days, nights, roads.’ Again in 1985: ‘My pleasure is in walking, lifting, placing, carrying, throwing, marking.’ In 1968 he showed a sculpture of sticks cut from trees along the Avon and laid end to end in lines on the gallery floor. Five, six, pick up sticks. Seven, eight, lay them straight.

‘A walk,’ wrote Long in 1980, ‘is just one more layer, a mark.’ Children, like Long, are passionate mark-makers. As any parent knows, a child is happiest when playing with surfaces that record its passage or presence. Ice-lidded puddles that smash like mirrors or crockery. Leaf-drifts that scuff and kick into clouds. A crayon scrawled along a white wall (a line taken for a walk). A stick dragged along railings, leaving its steam-engine sound-trail behind it. Dirty shoes tracking footprints across a kitchen floor. Long’s first landscape work, Snowball Track 1964, occurred when he rolled up a snowball, and then photographed the wobbly dark path of revealed grass left by it. In 1970 at the Dwan Gallery he wore muddy boots and stomped a spiral of smeared dirt on to the floor, the uncoiled length of which corresponded to a straight climb that he had previously made from the bottom to the top of Silbury Hill in Wiltshire. This was among the first of Long’s many daub-works from the 1970s, which he made by using his feet or hands to wipe, smudge, blotch and spread mud and soil on to the floor. Seeing black-and-white images of these works now, they resemble evolved versions of the hand-prints left by the Lascaux Cave artists around 17,000 years ago – or of a child’s first prints in mud or paint. Ontogeny recapitulating phylogeny.

When he was growing up, Long was lucky enough to be indulged in his compulsive mark-making. His parents let him draw all over his bedroom walls, creating a mural-in-progress. At the age of five he negotiated with his primary school headmistress over whether he could miss morning service if he spent the hour painting instead (his negotiations were successful). In 1966, while still an art student, he persuaded his neighbour to allow him to incise a work called Turf Circle into his manicured back lawn.

The lines of continuity from Long’s childhood into his adult work are multiple and clear. ‘My father used to take us down to see the spring tides [of the River Avon],’ he recalled. ‘I grew up playing on the tow-path… when I was a child I just used to find the River Avon a great place. And children are no intellectuals. They just play in the places which are nice to be in. So all my fascination with water, the roots of my art, developed in my childhood.’ The puddle splash, the muddy stick, the two-footed jump, fingers drawing pictures in the dust – how strongly those early river days have leaked into his later art. In the 1980s he extended his repertoire of daub-works, transferring them from floor to wall, and exploring new patterns and forms. He began to use his right hand as the brush: dipping it in a bucket of mud, then wiping the mud on to the wall to create splash paintings, then allowing the silt to drain down and disperse its alluvial deposits, forming arbitrary fans and deltas. The mud that Long uses most often for this work comes from the Avon, which he claims produces the most artistically helpful mud in the world, in terms of its adhesiveness and texture.

Lynne Cooke, in a 1983 essay that stung Long sharply, described his text-works as ‘wilfully precious’, and compared his photographs with colonial ‘trophies’. His art, she wrote, exerts a “powerful hegemony” (this at a time when the word hegemony was thrown around rather more often in art criticism than it is today). Long ‘attempts to order the world’, she wrote, ‘he… imposes order on nature’. But Cooke got Long wrong. He’s no hegemonist, nor an imposer of order. Rather, he is a discoverer of order, an experimenter in limit and form. A homo ludens, to borrow the title of Johann Huizinga’s synoptic 1938 study of the play-impulse, which so influentially connected play and art.

Richard Long

Campsite Stones Sierra Nevada 1985

Courtesy Haunch of Venison © the artist

Long the solemn child, then, whose work recalls Melanie Klein’s definition of play as ‘a serious form of meaningmaking – often compulsive, repetitive and anxious’. And, in this respect, he can usefully be connected with those artists who have seen the walk as play (which is quite different from seeing the walk as comedy). He can be placed in the company of, say, Bruce Nauman, whose 1967–8 video performance piece Walking in an Exaggerated Manner, around the Perimeter of a Square shows Nauman placing his feet – with the amplified care of a tightrope-walker teetering leagues above a city street – along the edge of a taped square in a room. And he can, perhaps, share at least imaginative space with Watt, the eponymous character of Samuel Beckett’s third novel, whose ‘way of advancing due east’ (wrote Beckett with playful seriousness in or around 1942) ‘was to turn his bust as far as possible towards the north and at the same time to fling out his right leg as far as possible towards the south, and then to turn his bust as far as possible towards the south and at the same time to fling out his left leg as far as possible towards the north’.