At the time of Turner’s death in 1851, the prevalent view of artistic production took decline in old age for granted, with an almost inevitable waning of physical capabilities and a slackening of mental strength. Even Ruskin, Turner’s most vociferous champion, assessed the artist’s closing years negatively. Ruskin considered the decade 1835–45 to be pivotal; it was ‘the crowning period of Turner’s genius’, as he put it, yet it also witnessed serious evidence of decline: loss of distinctness, absence of deliberation in arrangement and increasing feebleness of hand. When some of Turner’s last works were posthumously exhibited, Ruskin declared that he would ‘take no notice of… pictures painted in the period of decline. It was ill-judged to exhibit them.’ For him, their only value lay in their biographical testimony, with some features of their handling indicative of the mental disease that set in towards the close of Turner’s career: ‘In 1845, his health gave way, and his mind and sight partially failed. The pictures painted in the last five years of his life are of wholly inferior value.’

With respect to Turner’s work of the 1840s, although some patrons of his watercolours stayed loyal to the end, the exhibition of his oil paintings at the Royal Academy proved increasingly contentious. On his death the obituarists were clear that the work of his last years showed a great falling off. The account published in the Athenaeum, one of the most influential art journals of the time, declared that these later paintings were the ‘eccentricities of a great genius in which he of late years indulged, and which rendered it necessary that he should attach rings to his pictures (contrary to Academical requirements) in order to show which side of the picture should be hung uppermost, – those were his dotages and lees, and will in all probability sink in reputation and in price’. The same negative reaction was directed at Turner’s unfinished work. When he died 100 finished and 262 unfinished paintings were left in his house and studio in Queen Anne Street. The authoritative voice of the Art Journal considered that only five of the unfinished canvases were worth exhibiting to the public. When a select committee was established ten years later to assess the nation’s custodianship of the Turner Bequest, Ralph Wornum, the keeper of the National Gallery, reiterated this opinion, describing the residue of Turner’s studio as ‘unfinished sketches of every description, things which were found in rolls utterly unfit to be exhibited… mere botches; pieces of canvas with paint on them’. Wornum also had reservations about the quality of the finished work of the 1840s. He was in no doubt that the last years of production should be characterised by the word ‘decline’, largely because Turner’s concept of finish had weakened. As Wornum noted: ‘The details by which these effects were produced became rapidly more and more neglected, until in the pictures of the last few years they are so slightly indicated as to be generally unintelligible.’ The verdict was repeated in two biographies of Turner published in 1879. Cosmo Monkhouse described the artist’s last decade as a pathetic spectacle: ‘A great painter, the very slave of his genius, compelled to paint this and paint that at its bidding without being able to distinguish what was great and what was little, what sublime and what ridiculous… he appears to us in these last days like a great ship, rudderless, but still grand and with all sails set, at the mercy of the wind, which played with it a little while and then cast it on the rocks.’ Likewise, P.G. Hamerton, in his Life of J.M.W.Turner, R.A., chronicled a steady decline following the exhibition of The Fighting Temeraire in 1839. And although he admired the colour orchestration of the 1840s, he considered that all Turner’s work after 1845 had been produced in ‘a state of senile decrepitude’. Others were more forthright. Edward Poynter, lecturing to students at the Slade in 1873, described the later work as ‘repulsive’.

George Jones

Interior of Turner’s Gallery c.1852

Oil on panel

14 x 23 cm

Courtesy the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

The posthumous critical consensus on Turner was not absolute, but these opinions give an idea of how his later paintings were regarded by some of the more influential voices of the Victorian art world. In stark contrast, however, by the early 1900s the critical orthodoxy of the nineteenth century was turned on its head; for the majority of modern commentators, the acme of Turner’s genius was now represented by his later work, with special praise for the unfinished canvases. In 1906 Tate exhibited examples of his oil sketches and unfinished paintings together with some of the exhibited pictures of his last years. As far as the art journal The Studio was concerned, ‘they are examples of Turner at his best in his final manner. Hitherto condemned to obscurity as “unfinished”, these pictures anticipate to some extent the study of light which later became the inspiration of Impressionism’. The Studio’s critic was not alone. From the 1890s Turner’s achievement had increasingly been linked to Impressionism, asserting that in his final decade he had forestalled most of the discoveries that Monet and Pissarro had made in the 1870s. As his proto-Impressionist status became critically entrenched, so his less fully realised works might become worthy of exhibition after all – precisely because in their experimental procedures, fugitive effects and lack of finish they seemed to approach closer to the look of Impressionist work than anything he had successfully exhibited in his lifetime. According to the critic Lewis Hind, the unfinished work in particular moved the public to ecstatic appreciation of Turner’s visionary genius. As he commented: ‘Of all the periods of his art life there is none to be compared with the period contained in the few glorious years when he was past 60 and drawing near to his seventieth year, the period when light in all its manifestations obsessed him.’

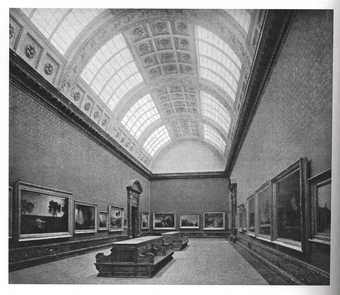

View of a room in the new Turner wing at Tate Gallery in 1910

© Tate

The construction of a purpose-built Turner Wing at Tate in 1910 saw his work housed for the first time in reasonable conditions (five rooms on the upper floor and four below), with a large amount of it on public display. When a new wing was added in 1926 for the modern and foreign collections, the visitor reached it after passing through the Turner galleries, the last room of which contained his later paintings and unfinished sketches. To provide continuity of effect, it was given the same décor as the first room of the modern and foreign galleries, where Impressionist paintings were exhibited. By curatorial sleight of hand Turner’s late work was thus put into conversation with Impressionism, as though it were some sort of prologue to Impressionism proper. His status as a proto-modern artist persisted into the 1960s. The artist and art historian Lawrence Gowing curated the exhibition Turner: Imagination and Reality for New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 1966. Unlike the more zealous interpretations of the early twentieth century, Gowing was insistent that Turner was no modern artist’s precursor, but had nevertheless revealed something about the process of painting, its potential to signify irrespective of its ostensible subject, that contemporary artists would recognise as an urgent concern. In New York a stark modernist setting was devised: the works selected were virtually all late or unfinished and they were shown in modern frames. As with the displays in Tate between the wars, so at the Museum of Modern Art in 1966, Turner’s later pictures were used to promote the idea of his modernity, although the location of the modern in art had now, of course, shifted its ground from Impressionism to abstraction. The following year Gowing worked with Norman Reid, the director of Tate, to present an audacious new setting for the Turner collection in London, closer to the by-now standard white cube gallery space of modernism than to the Italianate splendour originally envisaged for the Turner Wing in 1910. White plywood screens were positioned in front of the gallery walls. The original high vaulted ceilings were hidden by a velarium of butter muslin through which light was diffused, stretched across the room at the same height as the top of the screens. Simple modern frames were used and late and unfinished work was prominent. The implied invitation to the viewer was to see Turner as though he were a contemporary artist.

Installation view of Turner: Imagination and Reality at the Museum of Modern Art 1966

Courtesy Museum of Modern Art, New York

Turner’s emergence as a prophet of modern painting is a good example of the way in which the discourse of late style can alter perceptions of artistic achievement. While his stature as an important nineteenth-century British artist was never in doubt, his ultimate significance, for many, now lay beyond his historical circumstances. His late style, once identified as such, was placed outside the sort of contexts applicable to the work of his contemporaries. No longer contained by history, it could speak to the future. And the twentieth century’s fascination with Turner’s unfinished work can be partially explained by one other characteristic feature of late style: the idea that the aged artist is primarily working for himself alone, no longer required to subject his vision to public scrutiny, or so beyond caring that he is indifferent to criticism. If so, work left in the studio is not incomplete, but an authentic record of the artist’s uncompromised creativity. For some, indeed, it is the late style at its purest.

The Turner displays at the Tate Gallery 1967

© Tate

The modern interest in late styles is conditioned by our retrospective gaze: what the artist’s contemporaries may have found obscure or difficult seems to anticipate future developments. Criticism can therefore take pride in its discernment, for difficulty is an attribute of the modern movement and the critic is thus better positioned to engage with the more rebarbative aspects of an old master’s style. In that respect Turner’s reappraisal was not unique; in the early 1900s some critics aligned the later work of Rembrandt and Titian, too, with recent developments in painting. But Turner’s presumed anticipation of modern art has arguably proved more long-lasting than theirs, primarily because his use of colour as a compositional device lends itself to anachronistic comparisons with abstraction. For that reason Norham Castle, Sunrise, an unfinished painting of the 1840s, is probably as well known today as The Fighting Temeraire. While this incomplete picture may justify Turner’s significance for many people, its prominence in that regard merely reflects contemporary taste. Turner’s own thinking remains veiled.