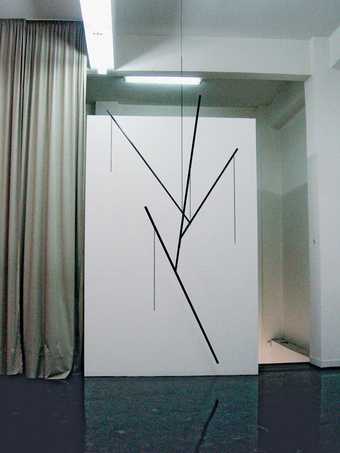

Martin Boyce

Into this Shadow 2005

Powder coated steel, chain

270 x 105 x 140 cm

Courtesy The Breeder, Athens © Martin Boyce

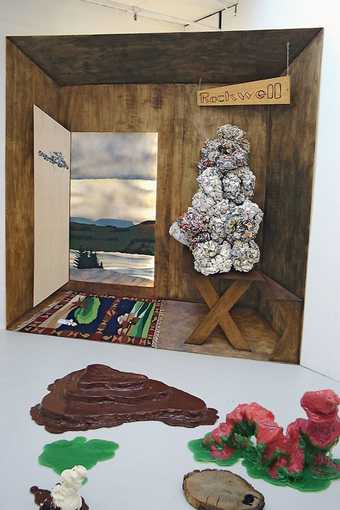

Esther Stocker

What I Don't Know About Space 2008

Installed at Museum 52, London

Black tape, foam core and paint

Dimensions variable

Courtesy Museum 52 © Esther Stocker

Here is your narrow room, floors and ceiling swathed with black-and-white stripes, V-shaped Constructivist protrusions spiking every surface. Here is your assumedly pre-Second World War abstract painting, a harlequinade of interknitted mauve/azure/tangerine polyhedra. Here is your blocky black post-Minimalist sculpture. Here, really, are thumbnail sketches of recent art by Esther Stocker, Anselm Reyle and Tom Burr, and if you squint, it is 1921 or 1935 or 1969, and if you don’t squint, it is very much the present moment.

New modernism is rampant. In 2005 at a symposium in east London gallery The Showroom entitled “New Moderns?”, French curator/theorist Nicolas Bourriaud characterised “altermodernism” – a term borrowed from Croatian poet Filip Erceg – as “a reloading of modernism according to twenty-first-century issues”, particularly the homogenising effects of globalisation. In 2006 Tomma Abts won the Turner Prize with her austere painterly revisions of modernist geometries for an age of abiding doubt. (On the Turner Prize shortlist last year was Goshka Macuga, another artist deeply invested in modernism.) In 2007, lecturing at the Frieze Art Fair, American critic Dave Hickey asked whether anybody had noticed that 9/11 had killed off postmodernism. Pretty hard to talk about the end of history under such circumstances, Hickey suggested. But the defensive language of postmodernism, with its lockstep ironies and bricolage of aesthetic pastiches, had already for some time previous been proving itself incommensurate with the persistence of pesky hardwired stuff in the human psyche: desires for a better world, regret at the one we’ve got, refusal to accept that progress is impossible (even PoMo’s pioneers got to feel as if they were actively closing a door, seemingly presuming that everyone afterwards would just stare sombrely at it), nostalgia, emotion in general and curiosity about babies and bathwater.

This refreshed attention to modernism’s potentials might be considered a classic generational response to a bequest of obsolete tools. Though increasingly prevalent in recent exhibitions – the Berlin Biennial, for example, which pointedly sited its contents in modernist venues – it has been swelling for some time. The aforementioned Tom Burr, for one, has been repurposing Minimalist and post-Minimalist aesthetics since the mid-1990s, conflating that art’s emphasis on the viewer’s body (and an otherwise assiduous muteness) with, on occasion, that of the gay cruiser, and more generally the policing of social space. Perhaps never more memorably than in Deep Purple 2000, his two thirds-scale, 82m-long remake of a former landmark in his home city of New York: Richard Serra’s contentious sculpture Tilted Arc 1981, here given a camp purple makeover, ostentatiously propped – like a stage, or something to consort behind – and with the curve returned as a signifier of the divisional 1980s, replete with reminders of Dionysian rock music and sexual politics. More recently, Burr has laced featureless black shiny boxes with wine glasses and brimful ashtrays (2003’s Black Out Bar), and adopted a spacious scatter aesthetic involving bulletin boards and photographic references (to, among others, Jim Morrison, Frank O’Hara and visionary curator A Everett “Chick” Austin Jnr) alongside hinged sculptures resembling collapsed bodies. A modified modernism that admits to bodily pleasure and casualties and decries the unspoken and closeted, Burr’s rigorous and poignantly commemorative art is an outrider in the continuum of the altermodern, whose proponents sift defunct modernity in search of what retains the potential for use.

Martin Boyce, meanwhile, likes to characterise his artworks as “undead”, and in his scuffed and plywood-patched examples of Charles & Ray Eames’s mid-century design classic furniture, such as 1997’s Now I’ve Got Worry (Storage Unit), modernism returns ghostlike, trailing philosophic counsel about how things slip inexorably in and out of style, looking bruised but unbeaten by the ravages of transit and offering instruction in disharmonious sentiment: nostalgia, threat, loss, revivification. In conversation, the Glaswegian artist denies that he’s “playing in the ruins” of the modern era. For him, installations such as Our Love is Like the Flowers, the Rain, the Sea and the Hours 2002) – with its skeletal trees made of strip lights, fragments of Mies van der Rohe-like furniture and bins bent dreamily into isomorphic perspective, all wrapped in a cyclonefence enclosure – are intentionally productive, compounding an admonition that everything must change with the potential to trigger miniature Proustian rushes that summon memories of one’s own personal, probably youthful, adventures amid cold modernist urbanism.

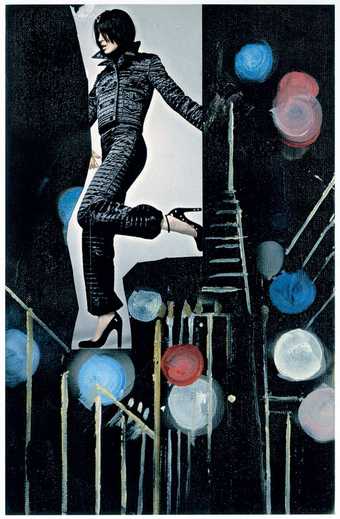

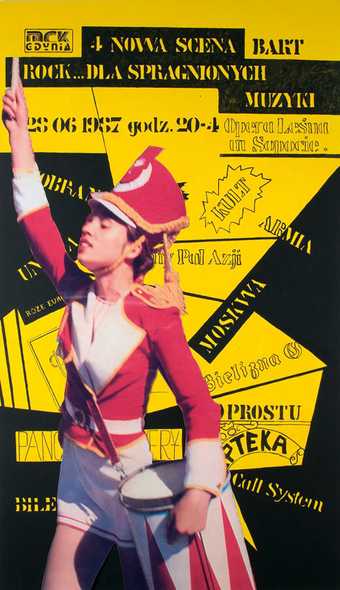

If Boyce rehearses and finds compensation in the destined diminishing and potential return of the modern in general, other artists have attended closely to specifics, treating quadrants of the modernist past as chapters to be rewritten or sedulously edited. Paulina Olowska has in recent years used an increasingly ramified aesthetic – paintings, photo-collages, videos, tapes of self-written stories, performance and installations – to sketch an imaginary feminist-modernist bohemia, a world of bobhaired strong women interwoven with visual cues (neon signs, film posters) from 1960s Poland, pointedly a period of relative freedom under the communist yoke. The Gdansk-born Olowska has, for example, convened provisional salons of modernist women, arranging, in 2004, her large fragmentary canvases of Djuna Barnes, Vanessa Bell, Virginia Woolf, Charlotte Perriand and more on wheeled supports so that they confronted each other, their conversation almost audible, in the salubrious environs of the Kunstverein Braunschweig. It’s a vision of a strong, connected female avant-garde within the modern, one that never really transpired: the sustaining of this dream cadre, and what the example might mean in the present, is what counts here. That Olowska recognises the fragility as well as the necessity of what she’s doing, however, was reaffirmed by her 2006 show at Warsaw’s Foksal Gallery.

Goshka Macuga

Cabin, featuring the works of Ian Dawson, Paul McDevitt, Declan Clark and John Spiteri at Cell Project Space 2003

Courtesy Cell Project Space © the artists

The key element was a looped presentation of Wolfgang Peterson’s 1984 film The Neverending Story, concerning a fantasy world that exists only so long as people believe in it: the free presentation of the movie itself, exploiting a loophole in Polish copyright laws, stood meanwhile as a testament to inventiveness over restriction.

Note that such art is reflexive, querying itself even while moving gingerly forward, fighting shy of certainty. Mai-Thu Perret’s ongoing project The Crystal Frontier (begun in 1999) similarly redrafts modernist histories in the service of a vigilant though provisional communitarian feminism. Its narrative spine is seemingly this: a group of Palm Springs women have quit the birdcage of housewifery for life as New Ponderosa Year Zero, a community seeking to get back to nature and hands-on craft in the New Mexico desert, where their collective life – an extension of twentieth-century idealist communes – refracts through those diary entries and objects the Swiss artist presents in galleries and museums. But this is an uneasy, deliberately unresolved anti-industrial romanticism. Perret’s displays, particularly in their mixture of faceless mannequins (seemingly representing the women) and handmade objects (seemingly bulletins from their world of production), weirdly elide the functional and the commodified aesthetic, and the artist evidently relishes this irresolution. Indeed her whole approach, dusted with Bauhaus and Constructivist references, clouds her stance on modernist communitarians, who’ve historically imploded melancholically, but, again, tended not to organise along female-only lines. It’s a possible future wrapped in a possible past, harshly illuminating real futures and pasts; if it only spurs a think-through of its own achievement’s conditionals, then Perret’s work is likely done. The new modernism’s ethos would frequently seem to involve being a believer and an agnostic simultaneously. Writing recently on Courbet for Artforum, the German painter Michael Krebber described one strand of contemporary painting as “practising Kandinskian formalism in the full knowledge that it cannot possibly work out, but sticking with it all the same”. True enough of, say, Victoria Morton and Joanne Greenbaum, but it needn’t be Kandinskian. Consider Anselm Reyle’s accelerated rush, in recent years, through a boggling range of post-war styles: Yves Kleinesque chromatic reduction, gestural and lyrical abstraction, colour-field, Minimalism, post-Minimalism. The Berlin-based painter’s canvases enact a kind of double-imaging, being hot, sensual, engaging and insincere. Reyle will crumple coloured foil, wrap it around canvas and seal it in a shallow Perspex box, and the result is both unarguably gorgeous and blatantly cheap (at least to make). He’ll arrange a changeably glowing spaghetti of multicoloured neon tubes in a darkened gallery and fulfil the conditions of “drawing in space”, while refusing any of the momentum, the will-to-newness, of high modernist experiment. His art, much of which originates in everyday found objects that Reyle liked the look of, is beautifully belated and a tribute to what continues to move us when it shouldn’t.

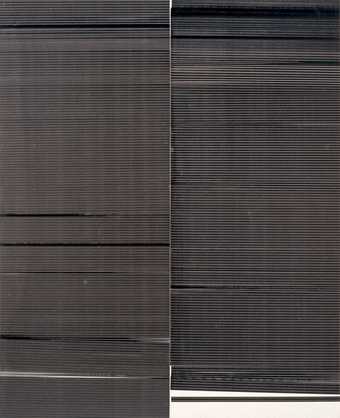

Wade Guyton

Untitled 2007

Epsom ultrachrome inkjet on linen

203.2 x 175.3 cm

Courtesy Friedrich Petrel Gallery, New York © Wade Guyton

Wade Guyton

U Sculpture 2005

Mirrored stainless steel

99.7 x 45.7 x 41.7 cm

© Wade Guyton

Wade Guyton

Untitled Action Sculpture 2006

Stainless steel

104.1 x 96.5 x 76.2 cm

© Wade Guyton

Not that it can’t be equally desirable to numb the heart as warm it. US painter Wade Guyton filters motifs through impersonal technologies, enacting a cold reprising of geometric abstraction. Behind his accretions of coloured grids and displaced stand-alone objects is time spent leafing through an immensity of books, particularly volumes on modern art. But closer to the surface there are the unlikely potentialities of flatbed scanners and industrial-size Epson printers, which, with their tendency to create unpredictable blurs and dribbles, scratches and pops when bolts of folded canvas are fed into them, have become Guyton’s distaff paintbrush, simulating expressivity in a way that tickles residual nostalgia for the artist’s hand (Reyle, too, paints his dribbles on afterwards) before we realise that we’re looking at mindless contingency. Confliction seems close to the heart of Guyton’s art: his recent “paintings” of large black Xs on unprimed canvas, for instance, are geometric abstraction reprised as muscular inaction, their motif halfway between a kiss (feeling) and a cross-out (refusal). They feel dead, but there’s something paradoxically bracing, even potentially redemptive, about seeing painting purge itself so thoroughly of humanism.

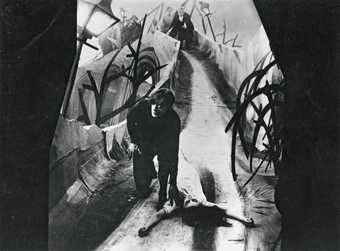

Looking at Guyton’s art, one can seem to be zooming backwards, watching the discredited enthusiasm and willpower that fired the modern era shear away like so much dead skin. In the case of Esther Stocker’s paintings, photographs and installations, which similarly root themselves in abstraction, we’re plunged into another kind of ground-zero uncertainty – one concerning a relation to physical space and distance. The Italian-born Stocker has been overt about this. Her recent show at London’s Museum 52 was entitled What I Don’t Know About Space, and, aside from black-and-white paintings in which grids fracture quietly along their axes and resemble distorting eight-bit graphics, its main stretch was a single, immersive installation. This was a room-filling riot of differently sized, predominantly V-shaped pieces of wood, covered in black gaffer tape and bursting forth from walls, floor and ceiling into the airspace, demarcating and seemingly measuring distances and angles; but, particularly when considered in tandem with the title, apparently doing so in a chaotic manner resembling a paranoid reflex action. We have been too bold, Stocker suggests, taken too much for granted that remains irresolute. We might need to start again from first principles; we might find that we cannot move forward from that. Again, modernism here presents itself as a temporal continuum to be entered at any point: a fossil field, of the sort implied by Goshka Macuga’s installations. The Polish artist is perhaps best known for her pioneering collapse of the roles of artist and curator: since early in her career, she’s presented cabinets and constructed environments devoting space to the practices of others, both living and dead, and to objects pulled from different cultural strata. But her work of late has increasingly overlaid theological and spiritualist concepts on to modernism, positing it as a spirit field – a land of ghosts – in, for instance, a carved sculpture of theosophist Madame Blavatsky levitating between two chairs (2007’s Madame Blavatsky). Her large-scale 2006 show at A Foundation in Liverpool, Sleep of Ulro, meanwhile, took the acclaimed sets of Robert Wiese’s 1919 Expressionist movie The Cabinet of Doctor Caligari as its starting point, setting mini-exhibitions, performances and theatrical tableaux within an architectural psychosphere.

Goshka Macuga

Boy & Girl installed at Tate Britain 2007

Mixed media

Dimensions variable

Courtesy the artist/Kate McGarry, London © Goshka Macuga

Mai-Thu Perret

Heroine of the People [Revolutionary] 2005

Papier-mâché, grid, acrylic and gouache, hairpiece, costume

90 x 85 x 85 cm

Photo: Marc Domage

Courtesy Gallery Praz-Delavallade, Paris I Berlin

© Mai-Thu Perret

Macuga, for all her increasingly dreamlike concepts of reanimation, appears devoted to a conception of the modern as sheer simultaneity: all its moments existing at once, quantum physics-style, in some accessible elsewhere, amenable to recombination. If this simultaneity descends from postmodernism, the contradistinctive issue for artists working today is what one does with the knowledge of it. In this regard it’s not hard to see why, aside from its surpassingly cool Möbius-strip narrative structure, Robert Zemeckis’s 1980s cinematic trilogy Back to the Future has been increasingly saluted of late by young artists and curators. (M/M Paris, the artist partnership, arguably got there first, lifting its typeface when designing the logo for the 2003 Lyon Biennial, It Happened Tomorrow.) Working on the basis that hindsight is 20/20, today’s take on modernism might be considered a fantasy of going back, Marty McFly-like, into vanished moments and tweaking them before they explode. Or, perhaps more accurately, of dragging past into present – “reloading it”, as Bourriaud would have it – hymning its potentials, exposing its failings for careful repair; and, in the process, tentatively resurrecting something that feels like hope.