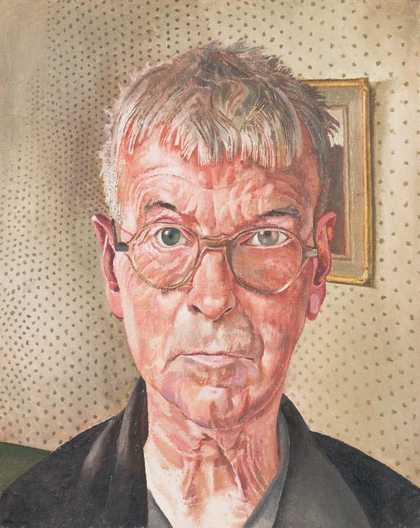

Sir Stanley Spencer

Self-Portrait (1959)

Tate

© Estate of Stanley Spencer. All Rights Reserved 2023 / Bridgeman Images

Ewan Gibbs on Stanley Spencer’s Self-Portrait 1959

I came across the 1959 self-portrait by Spencer on the cover of a book of his letters when I was seventeen. As a brutally honest depiction of a complex and fascinating artist in the last few months of his life, it puts me in mind of some of the late self-portraits by van Gogh. The time I first saw it I was so taken by the image that I made a linocut translation of it. I cannot look at this painting without thinking of the earlier self-portrait he made when he was 23.

Stanley Spencer

Self Portrait (detail) 1959

Oil on canvas

50.8 x 40.6 cm

Photo: Tate © Estate of Stanley Spencer/DACS, London, 2008

The detail which strikes me most is his neck. In the earlier painting he has a thick, elongated, bronzed, strong neck, which has degenerated over time into the pinkish, shrivelled, scrawny, wrinkled neck of a man who looks like he is in his late eighties, rather than his late sixties. I imagine that Spencer studied his neck in the mirror every morning as he dragged a razor across it. Over the decades it will have gradually become more difficult to keep the skin taut, leading to more nicks and cuts. He may well have spent the equivalent of eleven whole days shaving his neck between the 1914 and 1959 portraits. It is no wonder then that he knew it so well and paid such close attention when he painted it.

Learning about Spencer was a big influence on my decision to become an artist, rather than a graphic designer or brain surgeon. I had grown up in the Home Counties like Spencer and was planning on studying art in London, as he did. Now, eighteen years later, I have moved out of London with my family to live in a small Oxfordshire town which is not such a far cry from Cookham, where Spencer spent most of his life.

Self-Portrait was presented by the Friends of the Tate Gallery in 1982.

Robert Ryman

Ledger (1982)

Tate

Esther Stocker on Robert Ryman’s Ledger 1982

I think it is the deeper secret of a good painting that it doesn’t give you something, it takes something away from you. It leaves you with less then you had before, sometimes even with nothing. At least that is what happens with me. My old room-mate told me once that I am the dumbest person on earth for not knowing which things belong to me. This hurt. I hated hearing my human importance being measured by remembering (or not remembering) which teacup was mine.

Paintings such as Robert Ryman’s Ledger don’t tell you what to see or what to think. Whatever instruction you might be given for its better understanding, it only shows you it is useless. I like to hang out in a painting such as this, not remembering this and that, things I always thought I should know. My head slowly empties and I cannot find much in there anymore. I am always happy not to find things. It gives me a calm sense of freedom. It is so great not to get it, to know a little bit less. I think this is called liberation.

Ledger was purchased in 1983.

William Blake

The Primaeval Giants Sunk in the Soil (1824–7)

Tate

Rachel Kneebone on William Blake’s The Primaeval Giants Sunk in the Soil 1824–7, from Illustrations to Dante’s ‘Divine Comedy’, 8th circle of Hell

William Blake

Detail The Primaeval Giants Sunk in the Soil

From Illustrations to Dante’s Divine Comedy, 8th circle of Hell 1824–7

Pencil, chalk, pen and ink and watercolour on paper

37.2 x 52.7 cm

Photo: Tate

Why I love rain. One afternoon we belted on our cagoules, and set out walking for the weir. The heavens opened and we were amidst a torrential downpour, protective clothing inadequate against the full force of a thunder and lightning storm. Granny prohibited sheltering under trees; instead we turned and headed for home. On arrival we were saturated, so we had a hot bath and changed into our nighties. Including Granny. It was late afternoon, so our night-time attire felt decadent and, for this, illicit. Granny turned on the TV and went to make crustless egg sandwiches. We were left to watch a nature programme, featuring lions. Predators that hunted, killed, ate and mated.

The Primaeval Giants Sunk in the Soil was purchased with the assistance of a special grant from the National Gallery and donations from The Art Fund, Lord Duveen and others, and presented through the The Art Fund in 1919.

John Brett

The British Channel Seen from the Dorsetshire Cliffs (1871)

Tate

Gavin Pretor-Pinney on John Brett’s The British Channel Seen from the Dorsetshire Cliffs 1871

As the founder of the Cloud Appreciation Society, my attention is often drawn to what’s happening in the background of paintings. I like to see if the artist has managed to capture “what is true in the sky”, as Ruskin put it.

This seascape by John Brett is called The British Channel Seen from the Dorsetshire Cliffs. I like his use of crepuscular rays – those shafts of light that you can sometimes see when the shadows cast by clouds are rendered visible by the atmospheric haze. And Brett clearly delights in the appearance of sunlight falling in pools on to the sea surface. No wonder – this is invariably a beautiful sight. But from the perspective of a cloudspotter, Brett’s seascape contains one fundamental error: what he depicts above the horizon does not match what he’s painted below it.

You tend to see individual beams of sunlight strike the sea in this way when the sky is covered in a puffy layer of cloud known as stratocumulus that has gaps, or holes, in it. The sunlight shines down through the holes like searchlights, casting brilliant patches on the water. But Brett has painted a sky of small, individual cumulus clouds. In reality, these would cast darker patches of shadow on to a generally bright sea.

Brett’s aim is worthy of any cloudspotter: to explore the rich interplay between light and water – both in the form of the sea and suspended in the air. But no true cloudspotter would commit the error of divorcing atmosphere and ocean in this way.

The British Channel Seen from the Dorsetshire Cliffs was presented by Mrs Brett in 1902.