Just over half a century ago, in the dead of a Manhattan winter, Leo Castelli gave Jasper Johns his first solo show. There were gridded canvases, with each grid compartment filled by a letter of the alphabet or a number. Canvases called Targets bore patterns of concentric circles. And the Flags were covered edge to edge by the stars and stripes. The show was a hit. A taxi tycoon named Robert Scull wanted to buy everything on offer. No, said Castelli, that would be vulgar. Furthermore, it would have been bad business. The dealer could not afford to deprive his other clients of a chance to acquire work from what quickly came to be seen as the show of the year – 1958.

Alerted by a reproduction of Target with Four Faces on the cover of ARTnews, Alfred Barr of the Museum of Modern Art made a long, contemplative visit and eventually approved three canvases for the collection. Next, he persuaded the architect Philip Johnson to buy the first Flag painting, with the understanding that he would eventually donate it to MoMA. Few gallery debuts have been so applauded – and so disparaged. When Mark Rothko stopped by, he looked around at all the shamelessly recognisable imagery and said: “We worked for years to get rid of all that.”

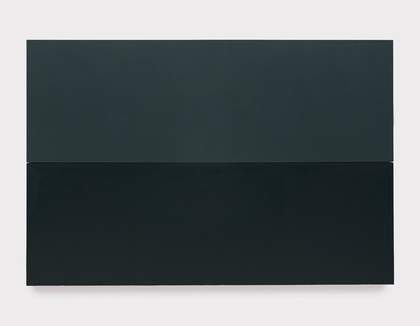

Since the late 1940s, Rothko had been filling his canvases with large, glowing expanses of colour. Earlier, he tried his hand at the Surrealist game of inventing new life-forms. Statuesque at first, his inventions evolved into distant relatives of jellyfish and other denizens of the deep. The immediate ancestors of these shimmering creatures were the human figures Rothko painted in the 1930s – city dwellers weighed down by glum and portentous feelings. From the start, he had struggled to reveal the human condition. We are not, he believed, merely members of society, crowding into the agora. Born with a vocation to meet one another on the plane of transcendent truth, we are spiritual beings. Yet mundane things often distract us from our spirituality. Sinking into solitude, we are unnerved by doubt and the “intimations of mortality” that Rothko invoked in a rare public appearance at the Pratt Institute, in New York.

Life is tragic, he believed. A tragedian without words, he laboured to rid his art of everything that might veil the presence of his redemptive and ultimately indefinable “idea”. This exalted je ne sais quoi must be directly, intuitively perceptible. Purging his work of figures and every hint of the space they might occupy, Rothko arrived at the luminous grandeur of his mature style in 1949. He was 46 years old. Two years before, Betty Parsons had given him his first one-man exhibition at her 57th Street gallery. Annual exhibitions at Parsons followed. Rothko’s “idea” had become visible and others were beginning to see it. Or so he hoped, despite the evidence. Whether dismissive or respectful, reviewers tended to describe him as a formalist. Worse, he was dubbed a decorator. None the less, he had an unreserved admirer in his fellow painter Clyfford Still, and he was convinced that Still’s thunderous praise would soon be echoed by an ever-larger audience.

As the 1950s got under way, Rothko and his colleagues found themselves, at long last, with lively careers. New York galleries were showing their work, and museums had begun to pay attention. In 1952 the Museum of Modern Art included Rothko, Still and Jackson Pollock in 15 Americans, one of Dorothy Miller’s taste-making exhibitions. By mid-decade, the work of Willem de Kooning, Philip Guston, Franz Kline and other Abstract Expressionists had appeared at the Guggenheim and the Whitney. Then came 1958, the year of The New American Painting, a roll-call of first and second-generation Ab Ex stars – everyone from Rothko and Pollock to Grace Hartigan and Sam Francis.

Organised by the Museum of Modern Art and sent on a triumphant parade through eight European cities, The New American Painting provided some recompense for the desperation and neglect that Rothko and his generation had suffered for decades. Now, they could tell themselves, they had fought through to art world success. Better yet, they had achieved art historical significance. Rothko once declared that he and his friends were “producing an art that would last for a thousand years” – a prophesy that the international success of The New American Painting seemed to have justified. Jasper Johns was dismissible, a purveyor of everything that truer artists had left behind. Soon enough, his banal and excessively legible stuff would fade, as better, more challenging art claimed the future for its own.

A month after the Johns exhibition, Castelli showed Robert Rauschenberg’s combine-paintings. Johns had presented familiar things in two dimensions. With furniture, bed clothes and all manner of other things – a ladder, buttons, a taxidermist’s eagle – Rauschenberg ushered familiarity off the wall and into three-dimensional space. The banal was becoming theatrical. Almost no one was pleased, but nearly everyone paid attention. And they took note a few seasons later when Claes Oldenburg opened his Store in a shop front on the Lower East Side. Here he sold Roast Beef, Cherry Pastry, Blue Shirt and other make-believe goods – crude plaster objects splashed with rough, mockingly Expressionist paint. The art of recognisable things was gaining momentum. Then, late in 1962, that momentum crested as The New Realists opened at the Sidney Janis Gallery at 15 West 57th Street.

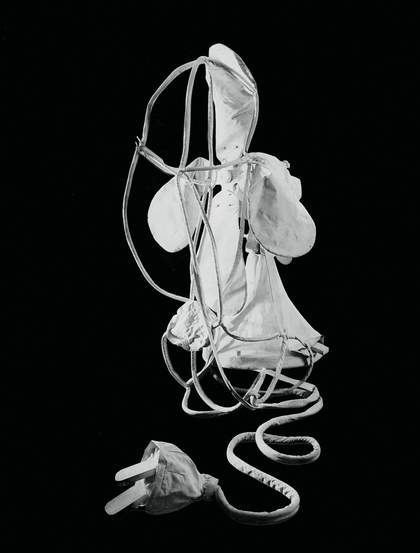

Claes Oldenburg

Pie à La Mode 1962

Muslin soaked in plaster over wire frame, painted with enamel

50.8 x 33 x 48.3 cm

Courtesy Museum of Contemporary Art, LA. The Panza Collection © Claes Oldenburg

Claes Oldenburg

Front cover of catalogue for solo exhibition at the Sidney Janis gallery, 1967 featuring Giant Soft Fan Ghost Version

Photo: Rod Tidnam, Tate © Claes Oldenburg

Oldenburg was included, as were all the other young artists who would acquire the Pop label – Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, James Rosenquist, Robert Indiana and, from the West Coast, Wayne Thiebaud. From Europe came Jean Tinguely, Enrico Baj, Arman and other practitioners of le Nouveau Réalisme, as the curator Pierre Restany dubbed it in 1960. Though these artists were less brash than the Americans, they too embraced the an-onymous, mass-produced things of ordinary life. They too seemed unserious, indifferent to art’s transcendent aspirations.

“Everyone is having a good time,” said Brian O’Doherty (the artist Patrick Ireland) in his New York Times review of The New Realists. As “ephemeral” as nearly all the work on view may be, he added, it signals “a definite trend, a possible movement”. By the end of 1962, this possibility was just about universally acknowledged as a fact. Abstract Expressionism was then. Pop is now. Or, rather, NOW!!! Rothko’s art for “the next thousand years” had been reduced to just another style – a look supplanted by a newer look.

The New Realists galled all the more bitterly because Janis had been Rothko’s dealer since 1954. He also represented Philip Guston and Robert Motherwell – leading members of the generation the Pop artists had so deftly confronted. By the end of 1962, Rothko and the others had left the gallery. Their indignant defection signalled a generational rift. In December of that year, the Museum of Modern Art addressed the conflict with a Symposium on Pop Art. The moderator was Peter Selz, a curator at the museum and a declared enemy of the new art. The panel included the critic Hilton Kramer, tireless eulogist of lost avant-garde glory, and the poet Stanley Kunitz, who declared that Pop Art’s “signs and slogans and stratagems come straight out of the citadel of bourgeois society, the communications stronghold where the images and desires of mass man are produced, usually in plastic”.

With this broadside, Kunitz echoed his friend Mark Rothko, who had written in 1947 of the liberating effects of hostility. Abandoning all hope of a sympathetic audience, said Rothko, the unloved artist is “freed from a false sense of security and community”. Unburdened by “his plastic bank book”, he finds the high road to “transcendental experiences”. For Rothko’s generation, plastic was the emblem of everything they found antithetical – not to say evil. For the Pop artists, plastic was just another material, on a par with paint and canvas. In 1965 Lichtenstein launched a series of landscapes that depend for their luminous shimmer on a lenticular plastic called Rowlux. Oldenburg’s soft sculptures employ all manner of plastics, not to mention vinyl and foam rubber.

Though the Symposium on Pop was overwhelmingly anti-plastic and pro-transcendence, the Museum of Modern Art was far less partisan, as it had shown early on with its acquisitions from Jasper Johns’s first show. Over the years, major works by Rothko, Still and Pollock were joined in the museum’s collection by Warhol’s Gold Marilyn Monroe 1962, Lichtenstein’s Drowning Girl 1963, Oldenburg’s Giant Soft Fan 1966–7 and other Pop blockbusters. Where MoMA led, lesser museums followed. As the 1960s wore on, critical attention leapt from Pop to Minimalism and onward to Minimalism’s offshoots – conceptualism, process art and the performance art of a milling crowd that included Scott Burton, Vito Acconci and Chris Burden. As these artists mortified the flesh with various degrees of intensity – and ingenuity – Rothko felt stranded, once again, with his solitary devotion to the spirit.

There was, of course, the worldly pleasure of being appreciated. Even revered. To some who found the 1960s bewildering or simply distasteful, Rothko looked like a monument wreathed in the already gathering mists of history. Moreover, his career was flourishing. After leaving Sidney Janis, he joined Frank Lloyd’s Marlborough Gallery. So did Clyfford Still and Adolph Gottlieb. Lloyd turned the work of all three into staples of the high-end market. Rothko enjoyed his success. After all, he had left Betty Parsons for the commercially astute Janis because Parsons had been unable to sell his work. When Janis leapt on a trend antagonistic to Rothko’s spiritually ambitious “idea”, the artist moved on to Marlborough.

In the long ago days of almost total obscurity, the sculptor David Hare had said: “We shouldn’t be accepted by the public. As soon as we are accepted, we are no longer artists but decorators.” Frank Lloyd and his clientele did little to persuade Rothko that they prized his art for the “transcendental experiences” it offered. Was his work being peddled as pricey decoration? To offset this uneasy likelihood, he concentrated on a series of canvases the de Menil family had commissioned for a chapel on the campus of the University of St Thomas in Houston, Texas. These immense paintings culminate the drift towards a smoldering darkness that began in the late 1950s with the Seagram murals, nine of which have resided in the Tate collection for nearly four decades. Perhaps it would be frivolous to see paintings in this register as merely decorative. But must we see them as the vehicles of a tragic, transcendent “idea”?

Rothko’s suicide in 1970 has fostered a myth of other-worldly goodness defeated by the evils of the marketplace and public insensitivity. The simplifications of this myth obscure much, including the possibility that the meaning – hence the aesthetic value – of Rothko’s art is still up for grabs. By the lights that guided him and his colleagues, an artist is either serious or not. Either an Ahab chasing the absolute in the existential deeps or a shore-bound servant of the moneyed, more-or-less-sophisticated classes. So the meaning of one’s work is either incalculably grand or pitiably trivial. Yet the alternatives are even harsher than that.

Not long after The New Realists closed, Warhol and his friend Ruth Kligman were taking a walk through Greenwich Village. When they ran into Rothko, she said: “Mark, this is Andy Warhol.” Rothko turned without a word and walked away. Having long grappled with enemies, real or imaginary, he saw in Warhol’s art something beyond his grasp: a blankness for which there was no accounting in his ultimately ethical scheme of things. Rothko had a traditional – one might say Romantic – conception of heaven and earth. Of redemption and damnation. Despite his church-going, Warhol was an utterly secular artist. So were the other practitioners of Pop and their unacknowledged cousins, the Minimalists. When these newcomers appeared in the 1960s, they opened up a despiritualised zone where Rothko’s moral strivings lost all their hard-won significance.

It was bad enough that swarms of hot new artists were seducing those who might have attended, respectfully, to Rothko’s lofty concerns. Worse, these newcomers saw his paintings as objects no less worldly than their own. Chatting with Warhol in 1963, the critic David Bourdon made a clever comparison. With their stacked bands of colour, he said, the Campbell’s Soup Can paintings “remind me of red-and-white Rothkos”. “But,” replied Warhol, Rothko “is much more minimal than I am. His image is really empty”. This was blasphemy, doubly so. First, Rothko didn’t want his paintings to be seen as images. They are to be felt as presences. Moreover, he wanted them to rescue us from the transient moment, to guide us upward to an intuition of eternal things. Fine, but what if his paintings are images, after all? What if these images are empty?

To these Warholian proposals, Rothko’s partisans can only say “no”. His colours open on to the plenum, the sum of all meaning, hence they radiate meaning at its most powerfully transcendent. To make their case, they can only repeat themselves, for there is no evidence to support these claims. Nothing supports them but declarations of faith. So Warhol’s bland remarks about emptiness join with the entire blasphemous decade of the 1960s to illuminate something fundamental about Rothko’s art. Its meaning is willed, first by the artist and then by the sympathetic viewer. In a room full of his elusive paintings, it is up to you to rescue them from emptiness. This is a heavy responsibility and not always welcome, as Rothko knew. Thus his lament – made first in 1947 and again and again throughout his career – that it is “a risky and unfeeling act” to send a painting out into the world.