In her peerless portrait of Picasso published in 1938, Gertrude Stein wrote: “A creator is not in advance of his generation but he is the first of his contemporaries to be conscious of what is happening to his generation.” The sentence could have been written for Lucio Fontana about his iconic work Spatial Light – Structure in Neon for the 9th Milan Triennial 1951. This aerial sculpture, which was suspended from the ceiling of the central staircase of the Palazzo dell’Arte, the Milan Triennial building, launched a visual language that was later to become an integral part of contemporary art. The 100-metre-long loop of neon tubing extended across the whole of the ceiling – a continuous sign of intersecting curves of light. The piece was a classic representation of what Fontana called a “spatial environment” and “spatial concept” – what he saw as overcoming the divisions in architecture, painting and sculpture to reach a synthesis in which colour, movement and space converged. Critics at the time described it variously as a lasso, an arabesque and a piece of spaghetti, but Fontana disliked this simplistic interpretation: “[It] is not a lasso, an arabesque, nor a piece of spaghetti… it is the beginning of a new expression; in collaboration with the architects Baldessari and Grisotti we have substituted for the decorated ceiling a new element which has entered into the aesthetic of the man on the street, neon, with this means we have created a fantastical new decoration.”

Another quote, this time from Fontana’s Spatial Manifesto 1947, seems to foretell the fate of this seminal work: “Art is eternal, but it cannot be immortal, it may live for a year or for millennia, but the time of its material destruction will always come: it will remain eternal as gesture, but it will die as material.” In fact, Spatial Light was destroyed, but the gesture remains. A copy was made in 1972, four years after Fontana’s death and authorised by his widow Teresita. Recently, it was given on permanent loan to the Civic Art Collection of Milan, and, after restoration, in September 2008 it will finally be reinstalled in the Triennial building, albeit in a slightly different location.

Fontana engaged in many collaborative projects with the most important architects of the day, in particular with Luciano Baldessari, who shared and supported his research at the 9th Triennial and, among other things, commissioned him to design the ceiling of the cinema in the Sidercomit Pavilion at the 21st Milan Fair in 1953. The predecessor of the 1951 neon, and also of his better known Spatial Concept paintings, was Black Environment, made with ultraviolet light and shown at the Naviglio Gallery, Milan, in 1949. It was a revelation which introduced a new concept of interactivity. As Fontana declared: “The Spatial Artist no longer imposes a figurative theme on the viewer, but puts him in the position of creating it himself, through his own imagination and the images that he receives.” The gallery ceiling was coloured with a violet, shadowy light, in which vague phosphore-scent shapes were hung: the viewer experienced a moving pictorial environment. “The spatial environment,” Fontana said, “is the obvious solution” for the introduction of change: “There can be no evolution in art that still uses stone and colour, it will be possible to make a new art with light (neon, etc), television, projection.” Prophetic words, uttered in 1949, which would give rise to Fontana’s Television manifesto of the spatial movement, in which he announced: “We want art to be freed from material. Through space, we want it to last a millennium even for transmission of only a minute.” The perception emerges of a language that would find expression over the years in the arrival of video projection and performance. And it may be no coincidence that the following summer at Black Mountain College, film images were projected on a series of Robert Rauschenberg’s White Paintings soon after the artist had returned from a stay in Italy.

Fontana was to open up the way for subsequent artists to use neon. And many did. For Bruce Nauman, Dan Flavin and Keith Sonnier, it was a key element. As well as Mario Merz, Joseph Kosuth and Franz West, a younger generation have also utilised it to great effect, including Tracey Emin, Martin Creed, Gabriel Kuri and Patrick Tuttofuoco.

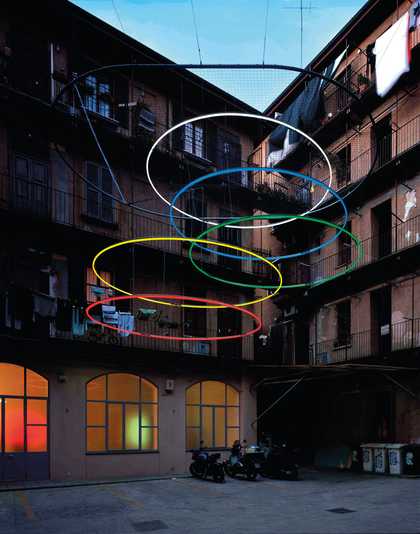

Patrick Tuttofuoco

Olympic 2005

Installed in a Milanese courtyard

Photo: Roberto Marossi

Private collection

Courtesy Studio Guenzani, Milan © Patrick Tuttofuoco

And Milan maintains its links with neon, as if Fontana’s gesture has continued to germinate in the place where it was first made. In the Villa Panza di Biumo in Varese, a few miles from the city, you can see Dan Flavin’s Varese Corridor 1974. The coloured light of the neon tubes seems to dematerialise the architecture and allows a vast corridor to become an immaterial lung, in which the reflection of the light enfolding the walls creates a visionary space that is superimposed like a skin upon the architecture itself. In Milan, Flavin’s spirit lives on in Red Church, a project completed in 1997, just two days before his death. Fluorescent neon lights of various colours were placed in the nave and the transept, and yellow light in the apse which had historically been covered with mosaics of gold tiles. New generation artists have also left traces of the relationship between neon and architecture in the city. In 2006 Martin Creed placed a white neon text, “EVERYTHING IS GOING TO BE ALRIGHT”, on the façade of the Palazzo dell’Arengario in the Piazza del Duomo – a contemporary epigraph for the building or Milan itself. Patrick Tuttofuoco suspended Olympic 2005, the coloured circles reproducing the logo of the Olympic Games, in the middle of a courtyard. The symbol of athletic energy and the neon tube, regularly encountered within the urban panorama, linked the structure of the balconied courtyards, typical of Milanese architecture in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, with contemporary art.

Luciano Baldessari, Lucio Fontana and Attilio Rossi

Cinema for the Sidercomit Pavillion at the 31st Milan Fair 1953

Courtesy Fondazione Lucio Fontana

Fontana’s influence goes beyond the relationship between light and architecture to encompass his idea of an “eternal gesture”. This is apparent in Franz West’s sculpture BRONZE/Am Brunnen vor dem Tore 2003. A stylised tree with a twisted trunk has foliage of light that seems to have been caught in the wind, and in that movement one can see the design of the Fontana’s Triennial neon. Like the viewers addressed by Fontana, West doesn’t work with a given subject, but “creates it by himself, through his own imagination and the images that he has received”. Gabriel Kuri’s floor sculpture with neon, 3W 2.5B 2005, has a different effect. Three tubes in coloured and white light of different intensities shine upwards from a base formed from cardboard Kleenex boxes. On these has been printed the image of a female eye, which seems to yield beneath the immaterial weight of light.

Neon light writing expands the imagination of places and images which would otherwise remain invisible. Mario Merz, for example, not only used neon tubes to pierce his paintings and his igloos, but also to trace out quick poetic lines and the Fibonacci sequence of numbers, which reveals the mathematic progression of nature adding on to itself (seen in the distribution of leaves, branches, the spirals of snail shells, etc). Merz transferred this symbol of infinity to buildings. Particularly moving are the permanent installations: The Flight of Numbers (2000) on the dome of the Mole Antonelliana in Turin and Fibonacci Sequence 1994 on the chimney of the Energia Power Plant in Turku, Finland. The numbers, which progress by adding the previous two in the sequence together, underline architecture’s aspiration to infinity, as a metaphor of thought and human action.

Joseph Kosuth uses neon and writing in his works for the re-reading of salient passages from philosophy and modern and contemporary literature. In his spectacular installation The Language of the Equilibrium on the Isola degli Armeni (shown at the Venice Biennale, 2007), a long text written in white neon surrounds the church, the cornice of the bell-tower and the wall that marks the boundary between land and lagoon, and conveys the inexhaustible vital force of this element. The island itself had become an architecture of illuminated words. Another vital yet different energy appears in the neon text pieces by Tracey Emin, who, announcing her feelings to the world, introduces an erotic current that demolishes the stereotype of woman as muse: Everything for Love 2005, More Flow 2006 and I Kiss You 2004. They may seem far removed in sentiment from Fontana’s Milan neon, but her spatial environments will, like his, “remain eternal as gesture”.