More than a group of artists marking the artistic modernity of the twentieth century, the association of Duchamp-Man Ray-Picabia sounds like a constellation. Linked by the complicities of life, the demands of friendship and artistic collaboration, these three men constitute a kind of occult triumvirate of the artistic avant-garde of the first half of the twentieth century. Occult, in fact, because none of them imposed his law and authority over the aesthetic destinies of their era.

All three had a fundamentally anti-authoritarian and actually libertarian conception of art and life. Until the end of their respective lives, they all held one another in perfect esteem. This was doubtless because each was able doggedly to preserve his freedom.

Of the trio, Duchamp is undeniably the central figure, because contacts and complicities between these three protagonists were chiefly organised around two pairs: Duchamp-Picabia and Duchamp-Man Ray. There was little direct and privileged contact between Man Ray and Picabia, and we rarely see all three together. However, we do see them in René Clair’s short film from 1924, Entr’acte, in which Man Ray and Duchamp are playing chess on the roof of the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, while Picabia sprays water at them. And also at Marcel’s famous wedding to Lydie Sarazin-Levassor in 1927, arranged by Picabia and filmed by Man Ray. Between Duchamp and Picabia there was a real reciprocal admiration which would not produce collaborative works, but which would be nourished by the same philosophy of life, the same way of life. Between Man Ray and Duchamp, it was more a question of aesthetic companionship as embodied in numerous four-handed collaborations.

Duchamp – Picabia: A friendship

linked to a way of life

‘One other characteristic of the century

is that the artists go in pairs:

Picasso-Braque, Delaunay-Léger, just like

Picabia-Duchamp… It’s a curious

marriage. A kind of artistic pederasty.’

Marcel Duchamp

Marcel Duchamp met Francis Picabia in 1910. The two men had absolutely nothing in common. One was a fils de notaire – a lawyer’s son – from the provincial petite-bourgeoisie; the other was descended from the Spanish aristocracy on his father’s side and the Parisian haute-bourgeoisie on his mother’s. One was lanky, introverted, ironic and discreet; the other massive, extravert, exuberant and vociferous.

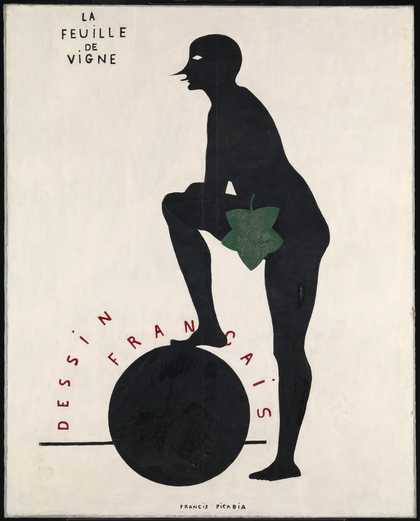

Francis Picabia

The Fig-Leaf (1922)

Tate

From the outset, Duchamp was fascinated by the couple formed by Francis and his wife Gabrielle Buffet, a beautiful and intelligent woman seven years his senior, a musician and friend of the composer Edgard Varèse, who had a crucial influence on Picabia’s art, in the sense that it was painting freed from its “sensory attributions”. Duchamp very quickly fell in love with Gabrielle, but their relationship would remain platonic, at least for as long as she remained with Picabia. While Gabrielle, who even said that she thought she had “initiated” Duchamp, very quickly understood his capacity to place his dry asceticism at the service of an “anti-natural” energy and a transmutation of aesthetic and moral values. Which could only bring him closer to her husband. Without a doubt Picabia likewise found in Duchamp a detached attitude to the world which diverted him from his natural propensity to excess. He showed Duchamp a way of life of which he had until then been unaware, and noisily immersed him in a social whirl that removed him once and for all from his universe as a fils de notaire. The world frequented by Picabia had nothing to do with the austere milieu of Puteaux Cubism. Very “right-bank”, he spent his time at the Weber and the Élysée-Palace, where he was in close contact with the anti-Symbolist poet and dandy Paul-Jean Toulet, another lover of opium and laudanum. Picabia adored women, cars, alcohol and drugs. Nevertheless, in Duchamp he found a sidekick who didn’t necessarily share his tastes, but with whom he was in intellectual and artistic harmony.

Picabia’s marginal position within the Puteaux group undeniably influenced Duchamp’s decision to remove himself from it. The duo already knew implicitly that beyond art they shared a subversive conception of life and the world. “The period between 1911 and 1914,” Duchamp confided in 1960, “was an explosion for us. We were rather like the two poles, if you like, each one adding something and exploding the idea by the fact that there were two poles. Had we been alone – he would have been alone, I would have been alone – perhaps fewer things would have happened within each of us.”

In 1909 Picabia made Caoutchouc (Rubber), considered to be one of the first abstract works in Western painting. Then he returned to landscapes, vividly coloured beaches outlined in black, influenced by Gauguin and Fauvism. Adam et Ève 1911 is close in spirit to the allegorical paintings Duchamp was making at the same time, such as Paradis, Baptême and Le Buisson (Paradise, Baptism and The Bush). Their shared way of putting themselves, both in theme and manner, at odds with the supposedly Modernist conceptions of their colleagues in the Puteaux circle would soon bring them together around a mecanomorphic conception of love and desire. But what linked the men most closely was a love of change and impermanence. “Basically I’m a compulsive changer, like Picabia. You do something for six months or a year, and you move on to something else. That’s what Picabia has done all his life.”

It was in New York that relations between Duchamp and Picabia would find their true consistency, in both artistic and personal terms. Proud of the “succès de scandale” of his Nude Descending a Staircase 1912 at the Armory Show in New York in 1913, and freed from his military duties (which meant that he did not need to participate in the great carnage of the 1914–1918 war), Duchamp, on Picabia’s advice, travelled to the United States in 1915. The latter had arrived in New York in June, claiming some vague mission to buy sugar from Cuba, which also freed him from his military duties in France.

Their great friendship was reinforced by their common aesthetic preoccupations. The mecanomorphic drawings that Picabia published in the magazine 391 – Portrait d’une jeune fille américaine dans l’état de nudité (Portrait of an American Girl in a State of Nudity) 1915 and De Zayas, De Zayas 1915 – were not unconnected to the work that Marcel was refining at the same time, albeit with less publicity, in his Lincoln Arcade studio: The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even 1915–23. Involved in all the radical and extravagant manifestations that made New York the transatlantic pole of the Dada spirit then flooding Europe (they invited Arthur Cravan to deliver his famous and scandalous lecture in 1917), the two partners were no less mistrustful of a movement which would, over time, come to constitute an aesthetic ideology. Gabrielle Buffet rightly remarks that New York’s “pre-Dada” activity was totally gratuitous and spontaneous and never involved a programme or a declaration of faith. It was the climate that favoured the excesses of two dazzling personalities, clashing in a competition of scandals and excesses, but also verbal, poetic and artistic inventions. Whatever the learned treatises might suggest, it was not premeditated for their subversive agitation to unleash a wave of negation and revolt which would affect minds, deeds and works for years to come.

When Duchamp, after a long spell in Argentina, came back to Paris in 1919, he linked up with Picabia, who had not yet met André Breton, but who was the figurehead of the spirit of Dada in Paris. However, he very quickly came to share Picabia’s reservations about a “movement” whose propensity towards a systematic way of thinking was contradictory to its primitive concerns. Their furious individualism could not be reconciled with the Dadaist political ideology as expressed both in Paris and Zurich.

In the spring of 1921 Picabia, suffering from a case of ophthalmic shingles that required a treatment with sodium cacodylate, summarily drew a vast eye at the bottom of a canvas entitled L’Oeil Cacodylate (The Cacodylatic Eye). During the months that followed, the friends who visited him at his studio in Passy were invited to inscribe their signatures on the space left blank on the canvas. It was on this occasion that Marcel Duchamp first added a second “R” to his new pseudonym, (Rose Sélavy thus became Rrose Sélavy – Éros c’est la vie). The intervention was discrete (if we compare it with Tzara’s), but was complemented by two small cut-out photographs, one of his head completely shaven from his time in Argentina, the other with a star-shaped tonsure. (It was Man Ray who, shortly after Duchamp’s return to Paris, had made the “official” photograph – Studio Harcourt style – of the artist as Rrose Sélavy. To accentuate the sitter’s femininity, Duchamp had retouched the picture, but most importantly he had substituted the hands and forearms of Germaine Everling, Picabia’s companion, for his own.)

After his return from Argentina, he hurled himself frantically and professionally into chess and casino games. In 1925 Picabia, seriously affected by his endemic depressive state, and having withdrawn completely from Breton’s official Surrealist movement, moved with Germaine and their son Lorenzo to the Château de Mai, near Mougins. Duchamp’s frequent stays in Monaco, where he sought to penetrate the “mysteries of roulette”, allowed him to see his friend Francis who, as he wrote to Brancusi, was “far less militant than before and seems contented with sunshine and the easy life. It is the best way of telling the bastards to go to hell”. With the complicity of Henri-Pierre Roché, the two partners worked on a scheme designed to sell 80 works by Picabia (paintings, watercolours and drawings) in a saleroom. “I agreed with him to organise a sale at the Hôtel Drouot; a fictitious sale, moreover, because the product was for him. But obviously he didn’t want to get involved because he couldn’t sell his paintings at the Salle Drouot under the title ‘Sale of Picabia by Picabia’.” The sale was held on 8 March 1926. A catalogue was published for the occasion (Catalogue of the paintings, watercolours and drawings by Francis Picabia belonging to Marcel Duchamp) with an essay, signed Rrose Sélavy, placing the works in historical perspective. Its conclusion clearly set out the aesthetic and political closeness of the two partners: “The gaiety of the titles and the collage of everyday objects reveal his desire to defrock, to remain a non-believer in these divinities created too lightly for social needs.

Relations between Duchamp and Picabia weakened between 1930 and 1950. The former was spending most of his time in the United States, while the latter was torn between his health, money problems and his various retreats. But during this period, they always kept a close eye on one another. In November 1953, when Duchamp learned that his old partner-in-crime had died in Paris of arteriosclerosis, he immediately cabled: “FRANCIS, à bientot.” He had lost the man with whom he had shared the idea of “joining nothing and craving no notoriety”. “It’s a pleasure for me to see that something exists in Paris apart from ‘arassuxait’ [a pun on art à succes],” he wrote to André Breton a few weeks later. “Plagiarising Jarry, we might have opposed ‘patArt’ to contemporary vulgarity. Sadly Picabia is no longer there to linger, and I see from the various articles about him that the donkey’s kick can take the form of stroking a dog.”

Duchamp – Man Ray: a joyful

collaboration

‘MAN RAY, masculine noun,

synonymous with joy, to play, to enjoy.’

Marcel Duchamp

It was at Ridgefield, a little country town in New Jersey, on the far shore of the Hudson, where a colony of artists and poets influenced by avant-garde ideas, individualistic anarchism and a Thoreau-inspired “return to nature” was set up in the late nineteenth century, that Man Ray and Duchamp met during the latter’s first stay in New York in the late summer of 1915. Emmanuel Radnitsky (alias Man Ray) was born in Philadelphia in 1890, but moved to Brooklyn with his parents at the age of seven. He attended the Ferrer Centre, an alternative, libertarian school formed in homage to the Spanish anarchist Francisco Ferrer, executed by the monarchy in 1909, and was taught by the “scissionist painter” Robert Henri and his former student George Bellows. At the time Man Ray’s pictorial work was strongly influenced by English Vorticism and Cosmism, or Amorphism (started by the art critic John Weichsel), two influential movements in the United States that claimed to follow Wilhelm Worringer’s abstract aesthetic and Max Stirner’s anarchist individualism.

In 1917 he set up a studio on Eighth Street in Greenwich Village and took the decision to photograph “what he couldn’t paint”. This was the year of the famous exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists, of which Man Ray and Duchamp were founder members, when Duchamp attempted in vain to introduce his “urinal fountain” (Fountain 1917), which subsequently went on to become an icon of modern and contemporary art. In the face of the reticence of the committee to exhibit this readymade, Man Ray withdrew his painting The Rope Dancer in a gesture of protest. From the outset, Duchamp found in Man Ray the ideal partner for all his eccentricities. Thus, for example, he photographed Duchamp who, on his return from Argentina, had had a star-shaped tonsure cut into his hair, a kind of homage to the “comet with its tail at the front” (Jura-Paris Road 1912), but also to Apollinaire’s poem Tête étoilée (Starry head). A lover of chess, he accompanied the Frenchman in long nocturnal games followed by frugal meals. Duchamp told him about Katherine S Dreier’s project to found a museum in New York whose purpose was to “introduce modern art to the Americans”. Man Ray suggested that she call it Société Anonyme (the French term for a limited company). The idea was adopted, and the name absurdly doubled by the administration charged with the task of registering it as: Société Anonyme, Inc.

For the opening of the museum in 1920, Man Ray offered his services to photograph the collection. By way of practice, in advance of the pieces ordered by Dreier, he suggested to Duchamp that he photograph the work he had been constantly refining for years, the famous Large Glass. But rather than take a conventional picture of the piece, Ray pictured the plates of glass lying down like a landscape, in the state of dilapidation in which he had found them, covered with dust. Duchamp would call this work, the fruit of their collaboration, Élevage de Poussière – Bringing up Dust, or Dust Breeding 1920.

Man Ray was to be the attentive partner in all the experiments by Duchamp in the field of what the latter called “opticeries”. The first incarnation of Rotary Glass Plates (Precision Optics) nearly dealt Man Ray a serious injury – one of the spinning plates broke loose and hit him on the head. Duchamp, keen to leave painting behind once and for all, wanted to tackle the moving image with the film camera that Dreier had given him. He got hold of a second, less expensive camera: “The idea was to join them with gears and a common axis,” Man Ray relates, “so that a double, stereoscopic film could be made of a globe with a spiral painted on it.” Their bid to develop the end product was a disaster: “The film looked like a mass of tangled seaweed.” Another attempt, showing Baronesse von Freytag-Loringhoven having her pubic hair shaved by Man Ray, was also destroyed while being developed.

The first appearance of Rose Sélavy as a representation of Marcel Duchamp disguised as a woman dates from the spring of 1921. It is a photograph by Man Ray made as the label for a perfume called Belle Haleine, Eau de Voilette and stuck on a Rigaud perfume bottle. Duchamp makes a pun on the original bottle label Eau de Violette. Duchamp’s Voilette is a combination of violette, meaning violet, and the French word velito (or little veil). And the inverted initials R S replace the slogan Un air qui embaume and the name of the Paris parfumier. This altered bottle would form the cover of the only issue of New York Dada, the magazine that the duo published in April 1921.

But it was the “opticeries” that would keep Duchamp busiest in the early 1920s. The fashion designer Jacques Doucet was very interested in these experiments and financed all the stages of their construction, requiring external expertise for the final realisation of Rotary Glass Plates (Precision Optics). Man Ray was once again a partner on this project, and detailed work on it was done in his own studio.

In parallel with this, Duchamp continued arm-wrestling with chance, attempting to exploit a “martingale to break the bank at Monte-Carlo”. In order to put this plan into effect, he issued 30 bonds of 5,000 francs, each at twenty per cent interest, for which he drew the design. “It was a lithograph of a green roulette table, bearing a red and black roulette wheel with its numbers, in the centre of which was a portrait of himself. But this portrait, which I made for him, was taken while his hair and face were in a white lather during a shave and shampoo,” wrote Man Ray.

Over two weeks during the summer of 1926, thanks to money inherited from his father, Duchamp shot an animated film in his friend’s studio with the help of the young Marc Allégret (a protégé of André Gide who would later make the film Journey to the Congo, and who was first initiated into photography by Man Ray). Anemic Cinema 1925–6, an anagrammatical title in the form of a false palindrome, is a seven-minute black-and-white 35 mm film, consisting of nine erotic puns inscribed on discs and ten optical discs along the lines of the Discs Bearing Spirals and the Rotoreliefs.

Until the end of Duchamp’s life, Man Ray would be his partner in all his adventures. In Paris, New York, Hollywood or even Cadaqués, their opportunities to collaborate (editions, exhibitions) were frequent, and always punctuated by games of chess. The invention of the readymade was a crucial influence on the works of the American artist, and there are countless nods to that emblem of modern art – from New York I 1917 and Obstruction 1920 to Ballet Français 1956. Similarly, his Rayographs to some extent act as the photographic equivalent of Duchamp’s optical experiments. Marcel Duchamp died on 1 October 1968. Some hours earlier, his last guests were Robert Lebel and Juliet and Man Ray.