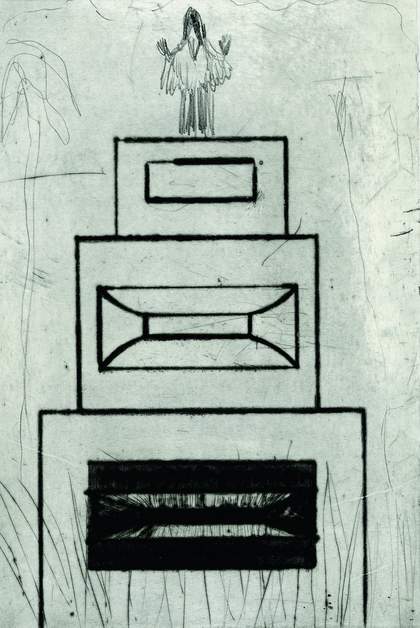

Peter Doig

Proofprint for Black Palms 2003

Etching

38.5 x 26.5 cm

Courtesy Michael Werner Gallery © Peter Doig

Once upon a time, I was sitting with the director of a major international museum and some of his public relations staff. Someone suggested – heresy of heresies – that on the cover of the museum’s next official publication they use a photograph “instead of an artwork”. (I understood what he meant: Weston or Evans, probably.) The director shot back without even thinking: “People don’t care about photography.” (I understood what he meant: older people.)

In any case, he was right. People don’t care about photography, not really, not in that way (they care about photographs, but that’s different). The proof is Peter Doig, because if they did care about photography, he would simply vanish. Doig exemplifies the reality that painting is an absurd vice, having been stripped of its pretence to cultural centrality and hedged in by photography. No transcendence, and it’s so much work. But he offers the lure of the image and the promise of transubstantiation, all the while demonstrating that this antiquated art is totally, onanistically free, free to occupy a margin of comment – on itself, on the world, on nothing at all.

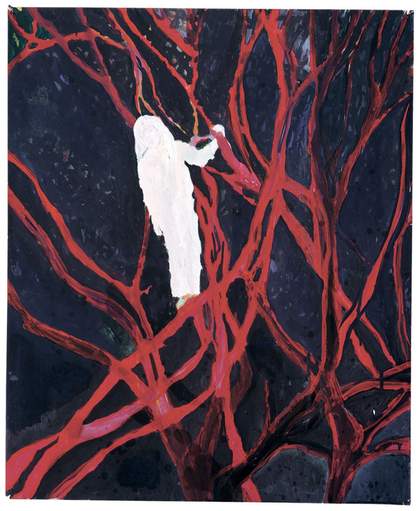

Peter Doig

Girl in Tree 2001

Gouache and watercolour on paper

63.5 x 52.1 cm

Courtesy Michael Werner Gallery © Peter Doig

Doig’s work shows us how far we have come, and how distantly we look back across a chasm at painting, the gulf being photography. The critical commentary on his painting and the interviews conducted with him are an index. First, he paints images with at least umbilical attachments to the so-called real world. There is something in the minds of critics – in all our minds still – that says painters have to have a reason, a pretext, to do such a thing, instead of just taking or manipulating photographs. And that’s not wrong. Think of the neo-primitivism of the 1980s, or, closer to home, the representational paintings of Gerhard Richter. Cecily Brown has a pretext. Doig (who grew up in Canada, lived in London and is now in Trinidad) has benefited from a certain Richter effect, that is, from anti-Platonist critiques, when it came to be understood that he, too, often preferred two-dimensional images as models to the common reality of the breathing world. One curator went so far as to assure us that there was no nature painting here, no plein air, only good studio conceptualism.

Yet for six centuries in the West such fabricated imagery has been standard operating procedure. In interviews, Doig always comes across to me as a little puzzled at having to explain his approach, to point out not so much the models for his imagery (is there any reason to care that 1993’s Blotter is based on a particular patch of Ontario?) as the fact that he actually combines elements from memory, and that what he is doing is not “remembering” or “depicting”, but fabricating a fantasy. To him, this seems like a perfectly reasonable way to go, and he himself is interested in the combinatory game – as long as it yields an image that satisfies him. He is doing precisely the thing that painting can do but photography can’t, which is to take the most extreme liberties in fashioning an alternative world.

Peter Doig

Blotter 1993

Oil on canvas

249 x 199 cm

Collection Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool

Courtesy Victoria Miro Gallery © Peter Doig

His world displays a few seams. When I was in graduate school, one of the favourite theoretical (or structural) questions was how do you know when you are confronting an allegory? This is the question that hovers over most of the writing about Doig so far, without ever being stated explicitly. One answer is incongruity – of time, place, or character, and for painting we would add visual incongruity, especially of mode or style. In Doig’s work, we would better call these collisions, which are masked to some degree by the dense and often compelling imagery he elaborates. The temptation with Doig is to do one of two things: to treat him the way the “New Image” painters of the 1970s – David True, Neil Jenney and others – were treated, and read the pictures as straight allegories. Who is the man in the canoe? What does the lonely figure in the landscape signify? In Architect’s Home in the Ravine 1991 is the home primordial? An archetype? A personal place? A place of memory? To me this suggests a deep nostalgia for iconography, a hunger for univocal significance that few contemporary works ever manifest and that the great Modernist works almost willy-nilly subverted by virtue of their iconoclasm. Doig is not reticent to name his sources – film stills, swipes from magazines, memories, album covers. It doesn’t diminish his imagination to do so. And it doesn’t banish the strangeness of the painting, instead it heightens it. The very strangeness that promises allegory in the end overwhelms it. PinkMountain (Part 1 & 2) 1996 just doesn’t yield to this kind of analysis.

The other side of this coin is the pursuit of what Doig himself so generously offers – the painterly reference. We know how satisfying it is to see obscure work suddenly clarified, even explained, by a thumbnail photograph of some art-historical source, such as putting Goya up next to kitsch sculpture by Jake and Dinos Chapman, or a Lucas Cranach next to a John Currin painting. With Doig, we might think of Arnold Böcklin’s Isle of the Dead (1880) and perhaps Doig’s Swamped 1990 or 100 Years Ago 2001, which contains the mysterious figure in the canoe modelled on rock musician Duane Allman. And we may link Canada’s Tom Thomson (The Jack Pine 1916) or David Milne (Bishop’s Pond (Reflections) 1916) with a Doig picture such as Night Fishing 1993 or Okahumkee (Some Other People’s Blues) 1990. For those inclined to play, there are echoes of everyone from George Caleb Bingham and Philip Guston to, and perhaps at a stretch, Doig’s Scottish great aunt, the colourist Anne McEntegart. Perhaps the most surprising thing is that a painter of Doig’s generation actually cares enough to treat the past as more than pastiche. For Doig, there is an illusion of tradition. He does not engage the technique, style or vision of the past as a primary issue, nor struggle with the notion of precursors and belatedness. No contesting with the dead; the dead are really dead, hence available. Something grabs him in particular images, but once summoned (requisitioned might be a better word), they are never quite assimilated. Stylistically, perhaps, yet they nag at us with their lostness, like old snapshots found stuck in a software manual. We can almost feel him turning them over in his mind, examining them, trying to gauge what accommodations they demand, and this helps to account for the work’s poignancy.

This sense that the whole world, even our mental experience, is a kind of museum or image bank through which the artist wanders begins to address the paintings’ visual texture. The more I study them, the more they look like outsider art to me. Everything – history, memory, the mass media in its various fecundating forms – offers itself to the artist as part of a free-floating repertoire of images and to a far lesser extent meanings. We think of the imagery of the outsiders Adolf Wölfli, Henry Darger and Martin Ramirez as sui generis, but they were inveterate borrowers. Like theirs, Doig’s imagination legislates under the most democratic principles in that nothing is privileged. We are used to this, of course, after Pop Art. Yet Doig’s paintings are not bricolage. They are more like those of William Hawkins, who would scour the streets of Columbus, Ohio, and the magazines and newspapers he collected there in search of images that would “give him a gift”, as he put it. It made no difference whether these were painted or photographed, imagined or borrowed, they were all images, resonant in ways it was impossible to articulate, but nevertheless all equal, and they were convened under the aegis of another broader image or idea, which coalesced through the painting in a process that melded free association and strict conceptualising. Hawkins didn’t begin with a collection of fragments, and neither does Doig, but the paintings can have a fragmentary quality.

Peter Doig

Driftwood (Yara) 2002

Watercolour on paper

55.9 x 35.7 cm

Private collection © Peter Doig

To me a similar disjunctiveness gives Doig’s paintings their odd feel, as if they were made up on the spot and carefully calculated at the same time, an image and a surface. There are several works – Blotter, Okahumkee (Some Other People’s Blues) and in a very different vein Lapeyrouse Wall 2004 – in which the purely visual element seems to be bumping against or uncomfortably coexisting with some other kind of description, offering a constant interpretive temptation. I can’t help thinking that in the lineage of Surrealism, his are the only paintings that manage to get past their own metaphors and to the associative texture of perceiving, the confusing tangle of visual and symbolic experience. No wonder he has said that he is after images that have resonance rather than meaning.

Adrian Searle has remarked that Doig has always left loose ends in his painting, often returning to visual themes after a hiatus. Just as the sources of imagery are not privileged, neither are ideas such as “development” and “breaking new ground” intrinsic to the avant-garde and to cognitive conceptions of art, and especially painting. By the Hegelian model, consciousness is a spiral, and knowledge is always self-overcoming. Forms exist to be contested and transcended in discrete works. But the image sources in Doig’s paintings are similar to fetishes; they keep demanding a response, constantly shifting according to some need the artist cannot name, and he returns to them whenever the image once again suggests itself.

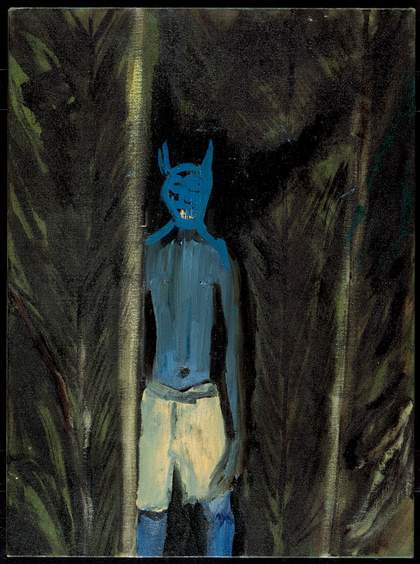

Peter Doig

Untitled (Paramin) 2004

Oil on linen

58 x 43 cm

Courtesy Victoria Miro Gallery © Peter Doig

Various critics have suggested that his career doesn’t seem to fit the model of producing discrete works, but is more like one ongoing image project. Perhaps, but even that is not consistent. There are many images that seem unlikely candidates for return visits and others that get recycled for reasons that have apparently less to do with their imagery than with the visual effects they have inspired. There is no Doig “style”, but rather extreme treatments that the imagery calls forth, consistent in their extremity. To me, this is the most fascinating aspect of the paintings, this strange interaction between treatment and image, how the treatment takes on a life of its own. It is the life of the picture; the image seems to exist at its behest. The only analogy I can think of is Pre-Raphaelite painting, with its radical and hallucinatory foregrounding, but that doesn’t get at the empty density of these works.

The Italian sculptor Pietro Consagra once remarked that art (he meant painting and sculpture) could not survive without its myths, either originary or Utopian. Doig proves that it can, as a kind of atavism, a response to something incommunicable, almost but never quite meaningless, like dreaming.