Juan Muñoz

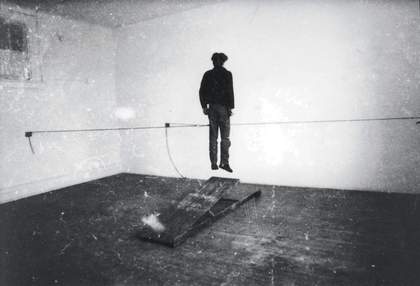

Performing a piece at P.S.1 Contemporary Art Centre, Long Island City, New York 1982

© The Estate of Juan Muñoz

Tate Etc.

Juan Muñoz first came to England in the 1970s, and, the story goes, saw the woman who would become his wife, Cristina, on a railway platform carrying a mirror. How important was England to him? Did he have a sense of himself as an artist fairly early on?

James Lingwood

I would say London was very important to him for a number of reasons, personal and professional. He was brought up in Madrid in the repressive atmosphere of Franco’s Spain, so his access to contemporary art was effectively restricted to magazines. As soon as he could get out, he did. His brother Vicente was already in London and in some kind of difficulty, so Juan came looking for him. This is the same brother whose face was cast for the figures in what turned out to be his final work in London, Double Bind 2001 in the Turbine Hall. There is a kind of symmetry to his relationship to the city. It was important to him right at the beginning, in the middle – because he showed quite early in his career at the Lisson Gallery and the Institute of Contemporary Arts – and at the end. London was always a productive place for him to think and to work.

Tate Etc.

When he first came here, what kind of art was he interested in?

James Lingwood

He was always looking at the great artists of the past and the artists of the present. He spent a lot of time in Tate and the National Gallery. He talked a lot about his encounter with Naum Gabo’s Head No 2 1916 and Jacob Epstein’s The Rock Drill 1913–14 at Tate. But he was very attentive to the work of the moment too. A scholarship from the British Council gave him the chance to study at the Central School of Art and then Croydon School of Art. The rethinking of sculpture at the time, the work of Tony Cragg and Richard Long and Bruce McLean, had an immediate impact. More or less, his first works were performances or actions in the street, documented by photographs.

Tate Etc.

Several years on, and by this time back in Spain, he began to make more considered sculptural work in the studio. He brought elements of the street, in particular the balcony, into his repertoire.

James Lingwood

The balcony represents something fundamental to his work – a concern with the dynamics of looking. It is a place from which the life of the street can be observed. He inverted this, so the viewer looks up to the viewing place, the empty balcony. The early sculptures also perhaps allude to the theme of the watchtower – there was a military observation post near his studio outside Madrid. Certainly, his first solo exhibition in Madrid in 1984, which featured various empty balconies and viewing platforms, plays with this idea of looking and being looked at. Again, this all reaches an ultimate realisation in the multiple viewpoints of Double Bind. The space of the street was a theme of recurrent interest, a place where its emptiness or normality might be disrupted by a particular incident or occurrence – though he was also intrigued by the sophisticated spatial play of Baroque architecture, the possibility of spatial distortion and artifice. Borromini, for example, was an architect who was an endless source of fascination for him. But then so was the person working his card tricks on the street – masters of the play with appearances…

Tate Etc.

Was it just architecture?

James Lingwood

He also loved some of the painters who had stretched classicism, such as Parmigianino’s Self Portrait in a Convex Mirror c.1524. In one of his pieces inspired by card tricks, he inscribes this title on to the photograph.

Tate Etc.

He also mentioned an interest in artists as diverse as de Chirico and Seurat.

James Lingwood

These are both painters who construct a particular kind of space: the metaphysical emptiness of the street in de Chirico and the spaces between the figures in Seurat’s compositions. For Juan, the issue of how to create a charged, active space, a kind of active emptiness, was critical. De Chirico and Seurat were working in two dimensions while, with the exception of the black-and-white Raincoat Drawings, Juan was primarily working with three-dimensional objects and then three-dimensional figures in the space of the gallery, or sometimes the space of the street, through which the spectator would be invited to walk. He liked the idea of a three-dimensional tableau in which movement had been arrested, time had somehow been suspended and sound and incident had been sucked away from the experience. So you get all these allusions to sound in his work, both in the Conversation pieces and in various figures which have quietly moving lips, such as Ventriloquist Looking at a Double Interior 1998–2000 – a little bit like you find in Seurat’s Bathers at Asnières 1884 with its boy in the river shouting.

Tate Etc.

But he wasn’t interested in a sense of narrative, even though we see figurative pieces that might suggest that?

James Lingwood

The figurative ensembles are like moments which don’t develop, so it’s as if it were you glimpsing a sequence in the street, a still or snapshot of a memory, but they are frozen. And in terms of narrative clues, they offer you only so much. One of the issues concerning readings of Juan’s work over the next few years is the relationship of the figure to the space. You see a piece in an art fair, or in a private home, and the preeminence of this relationship starts to disappear. But it was fundamental. It is always the man and the room, the figure and the space. The space between, the space which may have enabled or inhibited a kind of communication, was absolutely crucial to him. The catalogue entries to the sculptures list the materials and possibly the forms – five figures, a knife and a rope; bronze, steel, cord, etc – but really they should include the word space.

Tate Etc.

In this respect he looked to how artists such as Joseph Beuys installed their work. He also talked about how Richard Serra and Robert Smithson ‘activated’ space. But their methods might be seen as tricks…

James Lingwood

I suppose there was the development of a repertoire of devices which worked for him. But certainly the nature of space, and how sculpture could create it rather than simply occupy it, and how it could be experienced bodily as well as visually, that was of great interest to Juan. This was as true of Serra as of Giacometti, for example. With both of them, in their very different languages, the space was the key element for Juan – the space which the spectator or viewer needed to be in or walk through, as well as the form he was confronted with; the way in which the form was encountered, the way there was a kind of orchestration of the experience and the idea of suspending the experience, keeping it just there.

Tate Etc.

How did his use of the figure fit in at a time when many artists shunned figuration?

James Lingwood

It’s difficult for us now in 2007, with the current pre-eminence of figuration in every possible medium, to identify with the situation some twenty or 25 years ago and the sense of how corrupted, even reactionary, the whole tradition of sculptors working with the figure seemed to be – how contradictory any aspiration to radicality, and any use of the figure, were considered to be. He came to challenge this consensus, and it demanded considerable boldness to do so. He was not entirely alone, but it was a difficult journey.

Tate Etc.

Was he in contact with other artists about this?

James Lingwood

Certainly Juan had an ongoing conversation with Thomas Schütte (a conversation which happened through the works as much as through their words), and there were affinities with what Robert Gober was doing too. Schütte and Muñoz encouraged each other to work with the figure in a more substantive way. I think it’s no coincidence that they both initially began working with maquettes or mannequins or models, as surrogates for a figure, because that seemed just about possible. Gradually the work with the figure, both in terms of the complexity of the mise en scène and the attention to the modelling of gesture and form, became more prominent.

Robert Gober

Untitled (Leg) 1989–90

Beeswax, cotton, wood, leather, human hair

29 x 19.6 x 50.8 cm

Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery, New York © Robert Gober

Tate Etc.

In works such as The Identity of Departure 1987 or The Wasteland 1987 the floors are made in such a way as to create a particular optical effect that changes when you walk over them. Why did he do that?

James Lingwood

The optical floor is there to heighten the experience of the viewer, the sense of being not in front of the work, but within it. I think he was, to a degree, playing with Minimalism – sculptures that you could walk on, such as Carl Andre’s. But really he was more interested in Roman or Baroque floors with inlaid patterns of different coloured stone or marble that were made of certain numbers of repeating elements.

Tate Etc.

He didn’t like the coldness of Minimalism?

James Lingwood

I think he respected its toughness, but his work was to build on it, to confront it and not repeat it. And building on it involved, in some cases, deploying devices that were more historical and which had been considered a bit dubious.

Tate Etc.

He talked about a sense of being ‘embedded in history’, something that he thought about in relation to Jannis Kounellis’s theatrical sculptural installations made of mixed media. He wanted to be part of something, but he wasn’t of a movement; he wasn’t part of an ‘ism’.

James Lingwood

There is a passage in one of his interviews when he says that ‘we have become aware of the millions of stories that we did not allow ourselves to tell over the past ten years because of our suspicions of the conditions of expression’. He does locate himself in a European history – and identifies with a certain pathos which perhaps the work of Kounellis or Beuys might also embody. But he was interested in a different kind of sculptural tableau, one not made up with such symbolic or personal elements. It’s true he wasn’t part of any movement, but he did not travel entirely alone. He was part of a very significant rethinking of what sculpture could be in Europe. It was more like a disparate set of relationships, in which each individual had his or her distinctive identity, exploring their own territory, such as Schütte, Jan Vercruysse, Reinhard Mucha and, of course, Cristina Iglesias. They each went on their own journey. Perhaps I should mention the conversations he often had with his brother-in-law, the composer Alberto Iglesias. These were also very important for him.

Tate Etc.

He used dwarfs, smiling Chinese characters; there is also a seated Ottoman figure. The dwarfs suggest a reference to Velázquez paintings of the same subject, but where did the idea to use such figures come from?

James Lingwood

Sometimes artists stumble across a motif without necessarily having consciously sought it out, and then it remains with them for reasons that may not be readily explicable. The motif of the dwarf arrived for a very specific reason, which was to do with this exhibition called Theatergarden Bestiarium in Munich. He learned that the architect who had conceived the Baroque gardens of Nymphenburg Palace, François Cuvillies, was a dwarf. I think that is how the idea of the dwarf arrived in his work. The otherness of this figure intrigued him. Of course, he knew Velázquez’s paintings of dwarfs.

Tate Etc.

Juan came across a story about one of the dwarfs in the Spanish court who had a disease that meant he was constantly laughing. The court hired him because he was an uplifting presence.

James Lingwood

This was the story of one of the dwarfs painted by Velázquez. But anyway, the dwarf took on a life of its own in Juan’s work. He found dwarfs in Spain, a guy called George and a woman called Sarah, from whom he could make casts. How they were then used in subsequent works would depend on where they were shown. For example, when we made an exhibition in Dublin at the Museum of Modern Art in 1994, he placed a single white dwarf figure at the end of a very long corridor. It had an extraordinary effect on perspective – you couldn’t immediately tell its scale as you walked towards it, and it was almost as if it were getting bigger.

Tate Etc.

You worked with Juan on a number of projects and exhibitions. What were these collaborations like?

James Lingwood

There were close conversations, but it didn’t always mean I knew what was going to materialise! When we were preparing a big survey exhibition in the Palacio de Velázquez in Madrid in 1996, he brought in this huge lorry-load of Chinese-looking figures. They had remained a quiet secret he was working on while I was arranging the different rooms. He began to work out their installation. Initially, there was a figure in the middle, with all the other laughing figures surrounding it. Something about that didn’t seem right, so he took out the middle one, and then they were laughing at nothing. When it came to installing Double Bind, there were many changes to the way the groups of figures were placed, which shafts were inhabited and which were empty. He arrived in London with a repertoire of architectural details and figures and then tried out various scenarios, talking about them with Susan May (then curator at Tate) and myself. For quite a long time he had the thought that the geometric floor through which the lifts penetrated would also be populated. But in the last few days Juan decided it didn’t need the figures. This process of taking something away happened several times. There is a fugitive dimension to the work – something has often gone. Perhaps paradoxically this serves to make the experience of the work more present.

Tate Etc.

Someone described his ballerina figures as playful, but he said: ‘No, they are not playful, they are painful.’ What kind of sentiment do you see in his work?

James Lingwood

There is an existential dimension, a sense of aloneness, an exploration of the difficulties of communication. He talked a lot about the work being indifferent to the viewer, about engaging the viewer without acknowledging him. Perhaps that brings into play the aloneness of the onlooker. He wanted to withhold from overt drama – and maybe that’s what creates the psychological intensity or charge that I feel in his rooms. You walk within the rooms and as you get physically closer to the sculptures, do you really get closer to them? Not particularly. They elude you. They exist in their own space. And you’re in your own space.

Tate Etc.

Was he satisfied with how he made his work, or was he endlessly tinkering?

James Lingwood

There was a tremendous restless energy to the work, a need either to respond to challenges that were offered to him or to create challenges for himself. There was a lot of drawing, a lot of reading and a lot of talking; and in the studio a lot of experimenting with forms and motifs to create this repertoire of possibilities. He liked to keep things open until the moment of truth when working on the installation.

Tate Etc.

How did he feel he was received within his own country and elsewhere?

James Lingwood

I think he felt – and probably needed to feel – like an exile in his own country. And that’s not an unfamiliar position for artists to put themselves in. I think the fact that he was not part of any scene in Spain suited his restlessness. There is a certain kind of elusiveness, a way of keeping his freedom for manoeuvre as an artist.