A year or so ago I found myself trudging slowly through Tate’s online archive. Painting after painting appeared and disappeared. I was quietly disturbed by how little of the images I recognised. Many of the artist’s names rang no bells. It was not unlike wandering through a graveyard. It should (could) have been meaningful, meditative maybe, but instead was a cold-hearted list dedicated to the memory of time having been spent by someone somewhere. But just as if I’d found my own name on a stone, the surrounding landscape darkened and one image stuck out – Henry Lamb’s Death of a Peasant 1911. No doubt it appealed to me at the time because my dad was very ill and confined to his bed. The image began to burn slowly in my head. However, all through my dad’s illness I’d thought of the painting as showing a woman grieving over the death of her husband. In fact, it was actually the woman who had died. The light of external events had changed what I had seen, and I saw the picture as one depicting my own life. Since then the world has changed. My dad died in October. I had sat next to him as his eyes had dimmed, and I couldn’t be sure if he was here or not. Thinking back over those long minutes, I try to remember what was in my head and heart, but it is a blur. Somewhere in the middle of it all I see my dad putting on his coat, lingering in the hall for a few moments, opening the front door and closing it quietly after himself.

Sickbed and deathbed scenes are familiar to me through fiction and biography. Did they, I wonder, teach me anything about the reality of experience. We can know this, of course, only when it is our turn, and by then our own story has blotted out the drama. But I still see as clearly as the day I saw them first on TV the deaths of the father and mother in Terence Davies’s Trilogy, I hear the words of Addie Bundren in Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying (does she lay dying or is she dead?) recall her father saying “that the reason for living was to get ready to stay dead for a long time”. I am a fly on the wall in the room where the boy visits the dead priest in Joyce’s The Sisters; I am one of the whispering friends in Donne’s Valediction: Forbidding Morning. Valediction: Forbidding Morning. My dad owned an old Penguin paperback edition of The Metaphysical Poets, on the cover of which was a reproduction of the painting Sir Thomas Aston at the Deathbed of his Wife c.1635 by John Souch, an image of death which has haunted me ever since.

In Untold Stories (a book my dad and I seemed to be reading at the same time). Alan Bennett describes the last time he saw his father, and the Judas kiss he plants on his cheek as he leaves. I did share something of the author’s awkward helplessness and for a while feared that fear itself would make me do the wrong thing, something foolish and out of place, that I would regret for the longest time. I mentioned the Bennett episode to my dad and wondered what he made of it. He dismissed it with the usual impatience he had for humourless middle-class oversensitivity, but it taught me the lesson of being myself – even when being myself seemed so strange.

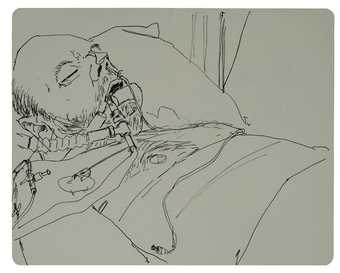

When I saw Lamb’s painting it made me think of watching my mum look after my dad. And that’s how we encounter art sometimes – by dropping on to it through the holes in our lives. Dad had been a working man all of his life until he suffered a heart attack in 1980 and was made redundant from the Standard car factory in Coventry. Over the following years he returned several times to hospital, but one December had a big heart attack, and then a bypass from which he never really recovered. The last twelve months of his life were spent in bed, with mum nursing him until the end. When he was sedated, or asleep, or just sitting up in bed, I drew him – just as I always had done when I was a kid. I always drew him reading or watching TV, sitting in the same chair. I was nearly 40 before I drew the right-hand side of his face. When we draw something on paper we seem to fix it in our minds too. It can become a balancing act between our ideas of the world and the world itself. As a result of sketching my dad in hospital, I can still see every tube going in and coming out of his body. Each day’s drawing became like the next, as each visiting hour became like the next. Dad was sedated for more than a week following his bypass, and familiar scenes of a family around a bed occurred twice or three times daily. As we sat or stood two at a time, we could see the same scene acted out at other beds throughout the ward. In the corridors we met the faces of other families with tender and heavy recognition. As the long days passed, dad slowly woke up. The world seemed bewildering and bright to him. I once saw my mum bend over the bed to kiss his forehead and my dad look up and kiss the inside of his oxygen mask.

George Shaw

Sketch of his father

© George Shaw

It came as no surprise then for me to find that I’d swapped the roles over in this painting. You can tell that the woman has not long died. She is in bed, and judging by her thin face, she has been ill for some time. I recognise the face of one who cannot bring themselves to eat and for whom being awake is heavy and tiresome. How seldom do I ever give the fact of being alive any thought – the movements of organs and works of chemistry. I recognise the colour of skin once life has been let out, of the shocking difference between one who is here and one who is not here. The woman holds on to nothing now. Her body, which was once a tight and ordered vessel of everything – stories, memories, happiness and pain – has hollowed itself out and become whatever the opposite of a promise is. The man, on the other hand, has screwed himself into himself. His eyes are shut tight enough to refuse the world outside. His clamped jaw holds words not spoken, his clutching hand holding on to nothing. I recognise her half-closed, or is it her half-open, eye retaining the secret of the last image, the empty mouth which has said goodbye to breath. I recognise the final touch and the efforts to remember it forever. I feel in him the massive weight of life, and in her the fragility of the ghost she has become. I recognise the slow distance forming between two things, of the world becoming something else and the numb fear of not knowing.

In his strange and beautiful essay The Two Versions of the Imaginary, Maurice Blanchot describes the corpse as being the image of the person it was in life. Here and not here at the same time. Lamb depicts the very point at which the woman departs from the world and from herself. The man’s holding on will gradually fade into a letting go as he opens his eyes to see nothing, a presence in absence only. How hard it is to bear the weight of knowing this, of letting this truth into ourselves to do its work. No wonder he keeps his eyes screwed shut.

For a while this painting remained an image. I saw it only as a ghost on the computer. I had no copy of it pinned to the wall. I could not find it reproduced in any book. It was not on display at Tate Britain. And yet the image continued to haunt me.

When I finally went to see the picture in the flesh, at the Tate store, it felt like walking into a mortuary. The paintings, stored in rows, are pulled out from the wall like vast vertical drawers some ten or twelve feet high. And there, among the racks, was Death of a Peasant. The paint on the surface was very dry and matt and seemed to absorb all the light that it was given. It offered precious little colour in return. It cared not that it was hidden here and seemed content with the knowledge that it had been painted. Shortly after leaving the storeroom I settled myself into a pub. By then, the canvas had been pushed back into its quiet tomb. I sat with my pint and my notebook. How did this little scene come to be painted? This is not a tragic or heroic death. But it is how most of us will witness the passing away of our loved ones, and how we too will die. Perhaps Lamb recognised this dreary and domestic fact of our death, but wanted through a very simple act of painting a picture to show that the death of a peasant is as graceful and dignified and memorable as any other in history or fiction.

Death of a Peasant was presented by the Trustees of the Chantrey Bequest 1944. The painting is currently not on display.