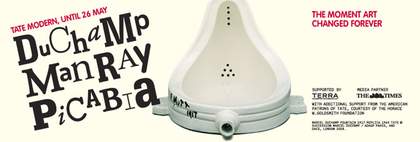

Carsten Nicolai on Francis Picabia’s The Fig-Leaf 1922

I have always liked Francis Picabia’s work, especially his early machine-drawings from the 1920s and his dot paintings from the late 1940s. In both lies a strength and simplicity to which I can easily connect. They didn’t have a message; it is pure abstraction, in which one can guess the joy of experimentation with form and logic. They have had a big influence on my work.

The Fig-Leaf is a good example of how prosaic and artwork can be. Picabia’s technique is very reduced – the black and white contrast of the figure and background look like a silhouette. With the slogans that go with it, the image reminds me of a design of an early twentieth-century poster. This everyday appearance, which is enhanced by his use of black car paint, suggests that it was actually not intended as an artwork, more a striking pose, a clear and defined statement.

There is a story behind the picture. It has been discovered that Picabia painted The Fig-Leaf over an older work that had caused an outcry at an exhibition a year before, By replacing the original picture with a figure that has lost its innocence, he was mocking his critics. The result us that under the obvious surface there is, without us being able to see it, a deeper level of interpretation. You do not always have to show and explain everything within a work; you don’t necessarily have to make things visible. I prefer that kind of subtlety.

The Fig-Leaf was purchased in 1984 and is on display at Tate Modern. The work will be included in Duchamp, Man Ray, Picabia at Tate Modern, 21 February - 26 May 2008.

Duncan Marquis on Paul Klee Walpurgis Night 1935

Paul Klee

Walpurgis Night (1935)

Tate

The first time I saw this painting it reminded me of the group of singing turds from the sci-fi spoof Flesh Gordon 2, or the orgy of melting bodies in the absurd horror film Society. Fleeting memories of half-remembered films, inherited from house of late-night TV, still influence my work as an artist today. I like the pathos and humour in the lumpen organic forms of Klee’s creatures; they seem to be metamorphosing into their own environment. His monochromic colour scheme and repeating brushstrokes suggest something like a luminous primal sludge. It is hard to tell what these creatures are or what they are doing, but the title and historical context give us a clue.

Klee named the work after the German Walpurgisnacht folk festival held on the May Day evening, when witches gather on the Brocken in the Harz Mountains to dispel evil spirits. Subjected to the Nazis’ witch-hunt on “degenerative” modern art, Klee was dismissed from his teaching position at Düsseldorf Academy in 1933. He made this painting after returning to his native Switzerland to avoid further persecution. In medieval Europe witch-hunts were often used as a political weapon, exploiting superstition to dispose of undesirable individuals. Witchcraft, as we know it in popular culture, is a demonised account of pagan rituals that were suppressed by the Christian church. Earthly paganism worshipped tangible nature, the opposite of Christianity’s metaphysical faith. Klee once described himself as a “medium” for nature – as if making a painting was akin to conducting a séance, with ectoplasm flowing from his brush. His statement mystifies what an artist does, and projects spirituality on to nature – in spite of nature’s indifference to our gaze. But ultimately, the ambiguity of Walpurgis Night leaves it for us to decide if the creatures are malign forces such as the Nazis, or the quarry of witch-finders (such as Klee himself), or maybe something else entirely.

Walpurgis Night was purchased in 1964 and is on display at Tate Modern.

Paul Klee

Detail, Walpurgis Night 1935

Gouache on cloth laid on wood

50.8 x 47 cm

© DACS, London 2007

Piers Faccini on Francis Towne’s Monte Cavo, I 1781

Francis Towne

Monte Cavo, I (1781)

Tate

When I was a child my father, who was Italian, would take our family every year to Italy, not far from where Francis Towne made this watercolour. My memories contain the imprint of those faint blue hills. Back then I didn’t know that it was that I longed to see again whenever I was in the throes of a bleak English winter. Today, clumsily, I can pin words on to the paper of that longing.

I’ve been chasing the light of the blue in those hills ever since, and I ended up catching it in the foothills of the Cevennes in south-west France, where I now live. I see that same colour under the same dissolving haze each day from the studio where I write songs and paint.

Perhaps Towne felt the same reverence towards his subject when standing under Monte Cavo more than two centuries ago. I like to picture him inhabited by the soul of a Japanese Zen monk, silently bowing to the futility of ever attempting to describe the wonder of what he’s seeing, before picking up his brushes and painting it all the same. I’m glad he did because, in the end, he saves me from the inadequacy of my own words and I become the child that I was, silently gazing at those hills.

Monte Cavo, I was purchased as part of the Oppe Collection with assistance from the National Lottery through the Hertiage Lottery Fund in 1996. It is on view at Tate Britain.

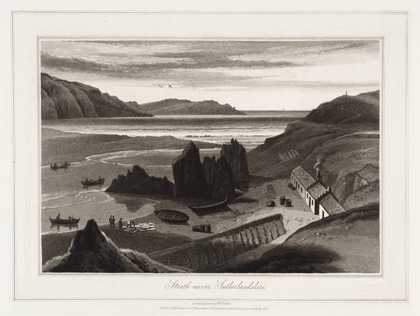

Andrew Graham-Stewart on William Daniell’s Strathnaver, Sunderlandshire, from A Voyage Round Great Britain 1813–23

William Daniell

Strath-naver, Sutherlandshire ()

Tate

This image does not actually depict Strathnaver, but rather the mouth of the River Naver in Torrisdale Bay. The scene is of salmon netting at one of the most prolific locations historically for this lucrative activity in Scotland’s far north. Netting finally ceased here – for conservation reasons – in the mid-1980s. Indeed, right across the wild Atlantic salmon’s range, netting has been severely curtailed in the past 25 years.

In the 1960s, of every ten juvenile salmon that went to sea, almost 50 per cent survived their miraculous ocean migrations and returned to their natal rivers. Marine survival has since plummeted, because of factors relating to global warming, to less than ten per cent. It is almost universally accepted that there is no longer a surplus that can safely be cropped for the fish-monger’s slab.

However, upmarket fish dealers and the catering trade are still supplied by a few legal netsmen, exercising their “rights”, and the ruthless poaching brigade. Premuim prices, buoyed by the vacuous mantra of celebrity chefs, encourage maximum exploitation. This, in turn, undermines conservation efforts and Scotland’s salmon angling industry, which provides up to one in seven jobs in remote rural areas; anglers, who release more than half the salmon they catch, fund vital conservation work. Stocks of the king of fish are fragile at best and commercial netting is now simply unsustainable. We should think very carefully before putting netted wild Atlantic salmon on our plates – the true cost is not reflected in the price.

Strathnaver, Sunderlandshire was presented by Tate Gallery Publications in 1979.