In the moment of the photograph, a happy occasion is touched – and instensified – by awkwardness. For the elderly man did not expect to be kissed by the young man with a late 1960s haircut. One wonders if the luminous young woman was entirely ready to see this happen. On the other hand, why not? It was, after all, the late 1960s, when the unexpected was expected and still felt fresh.

The elderly man is the painter Barnett Newman. The occasion is the opening of a solo exhibition, one of his last. He died in 1970. The woman is Viva, not just a denizen of Andy Warhol’s Factory, but a “superstar”. And not just a superstar, but the only member of Warhol’s entourage – Edie Sedgwick aside – who possessed star quality. She was possessed, in turn, by unmanageable impulses. Or perhaps she had them under strict supervision. In any case, Viva once proposed marriage, on camera, to the man who was at that time filming her – Michel Auder, who we see planting a kiss on the cheek of Barnet Newman.

Eventually, Auder exchanged film for videotape. He acquired a heroin habit and kicked it. He married Cindy Sherman, then divorced her. Along the way, he produced a sprawling body of work, which includes Cleopatra 1970 an epic shot in locations ranging from the sun-struck streets of Rome to the wintry landscapes of upstate New York. The leading role is played by Viva, who impersonates not only the ancient Egyptian queen, but also Elizabeth Taylor impersonating the ancient Egyptian queen in the Hollywood version of the story. Viva’s Cleopatra is a harridan, dazzling and demanding. In the Warholian orbit, art is driven by all that it glamorises: chiefly, impulse and need. Always social, often sexual, these are forces conducive to collaborative bedlam.

Often it was enough for Auder to record the unrehearsed behaviour of friends, as he did for Chelsea Girls 1971–6 with Andy Warhol, which shows Andy, Viva and Brigid Polk entangled in a long, sometimes contentious conversation. On Warhol’s scene, art was play, serious by virtue of the ironies it generated. When play-acting was sufficiently hip, the actor defeated the role. Or the opposite happened, and actors lost track of themselves in the mirrored labyrinth of the ensemble. For Michel and Viva and others on their scene, art was a flirtation with others who offered the risk – or the hope – of make-believe obliteration. So there had to be a scene, a crowd of initiates with whom to flirt. For Barnett Newman, art was something entirely different.

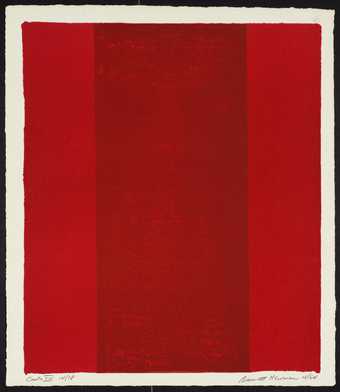

In 1965 he declared that the subject of his paintings is “the self, terrible and constant”. A militant individualist, Newman counts as one of Herman Melville’s “Isolatoes”. The word appears in Moby-Dick, where Melville explains that Isolatoes are those pioneer spirits disinclined to acknowledge “the common continent of men”. Each explores “a separate continent of his own”, and of course the prime instance of an Isolato is Captain Ahab, the monomaniac drawn from the land to the sea by the white whale, his “constant and terrible” obsession. Newman was an Ahab by vocation, but not by temperament.

When I arrived on the New York art scene, the 1960s were just ending. Avid for the local folklore, I learned that Jasper Johns was a sphinx, but not the sphinx, because Andy was also, in his own way, sphinx-like. I learned of De Kooning’s binges and Rothko’s melancholy. People were still talking about Jackson Pollock, how he had gotten up to this or that sort of mischief at the Cedar Bar. How his deathly accident may well have been suicidal. And I kept hearing about Barnett Newman, especially from younger painters, who told of his startling generosity.

The art world is, among other things, a hierarchy. Older artists do not appear in the studios of newcomers. Yet Newman did, despite his seniority and the aura of historical import that wreathed him during the last ten or fifteen years of his life. Long afterwards, a painter would reminisce about the warmth of Newman’s presence and his sympathetic response to work that was nothing like his own. With a bit of mythologising, visits such as these could become life-shaping events. “Because of Barney,” more than one painter told me, “I realised that I really am a painter.”

In 1965 Newman was invited to the eighth São Paolo Bienal. Among others in the American contingent were Frank Stella, Donald Judd and the writer Elizabeth C. Baker, then an editor at Artnews. Baker recalls long, tropical days spent with Newman as he trekked from one São Paolo studio to the next, in the role of cultural ambassador from the United States. He was always responsive, always encouraging. He seemed to feel, says baker, that he had a responsibility to support the very idea of being an artist. At ease with himself and others, he treated art as an international enterprise – open to all and buoyed up by common interests. Yet it was in the catalogue of that year’s bienal that he invoked “the self, terrible and constant”. And the sole inhabitant of its boundless landscape. Thus he opened a gulf between two ideas of art.

On one side, art is a shared enterprise. However jealously distinctive artists may be, they need a community of colleagues to give them a sense of themselves. There is a republic of art, and citizenship is a kind of mutuality. On the other side of Newman’s gulf, genuine art is the province of Ahab-like souls animated by a single, transcendent obsession. There is no republic of art, only the wilderness of the self, in which it seeks its true image. Or a brash newcomer seeks to expunge the image of a predecessor, as Robert Rauschenberg did, quite literally, when he erased a drawing by Willem De Kooning. The need is for distinctions, the sharper the better, and artists are not the only ones who feel it. As they chart shifts in style and draw up canons, critics and historians downplay continuities and evidence of camaraderie. Concentrating rather on clashes and disruptions, they picture the terrain of art as endlessly contested. As indeed it is.

It is also a peaceful kingdom, where lion and lamb find any number of ways to get along. Likewise, Barnett Newman was not only an extreme individualist, but also one of those figures of authority who knows how to soften his edges, moderate his tone, for the sake of a cohesion we can see as an aesthetic or social or even vaguely political. Warhol once said that only Barney managed to go to more parties than he did. This remark sounds like yet another bit of Andy’s conversational fluff until you realise that the art world could be described as a succession of parties.

We usually describe it as something like the opposite, an arena where conflicts are cultivated – where Frank Stella rejects the “hullabaloo” of Abstract Expressionism, Willem De Kooning sneers at Pop Art, and so on, down through the decades and across the centuries. Yet the parties continue and the battle lines are endlessly blurred.

This blurring is noticed, but only out of the corner of the art world’s collective eye. That eye usually focuses on disjunctions, not unities, and so it is a mild surprise to see a couple of Warholians, Viva and Michel Auder, getting on so well with Barnett Newman, a patriarch from the heroic years when Pop Art was unimaginable. And surprising, as well, to see Newman on the verge of melting with un-patriarchal delight. Though the occasion is his, Viva and Michel have set the terms of the encounter. For the moment is theirs. They have defined it with their gorgeous hair, the nonchalant refinement of their clothes, and the shining audacity of their faces.

Along the lower edge of the image, one notices Newman’s monocle, an affectation that continues to resist interpretation. Did he want his admirers to see it as the accoutrement of an Edwardian gentleman? But his politics were egalitarian. Did he borrow his monocle from the stereotype of a Parisian connoisseur? Possibly, and yet, several decades before Donald Judd allowed that he would be happy to see the traditions of Europe “go down the drain”, Newman had announced that Paris was over. From the mid-1940s onward, New York would be the capital of art. Its meaning inscrutable, his monocle sets Newman adrift in time. Thus it leaves him completely available to the present, as defined late in the 1960s by Viva and Michel. They are temporarily embodied. He is Ahab, beguiled by timeless absolutes, but a kindly Ahab, persuaded, in the moment of the photograph, that the commonalities of art, not the conflicts, are all that ultimately matter.