Like most men of a certain age, my grandfather had a limited supply of stories that he used to tell whenever the opportunity arose. Many of them concerned his family history. I don’t know how many times I heard about the drawing that used to hand inside the front door of the house in Norwich where he and my grandmother lived when they retired, but over the years repetition dulled the details. I knew the drawing was by the Victorian painter J.E. Millais – or rather, I knew it was a copy of a drawing by Millais – and I knew it was of a family called Lemprière, but it wasn’t until my grandfather died, and my parents inherited the picture, that I began to think about what it was, and what it must have meant to him.

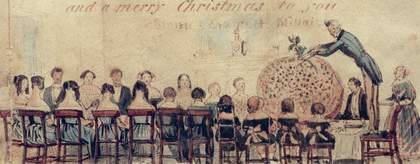

Detail from an illustrated letter by Sir John Everett Millais, Bt to the Lemprière family 1843–4

Photo: Thomas Haywood © Courtesy private collection

It’s a portrayal of the Lemprière family on Twelfth Night, when it gathered to cut the cake traditionally served to mark the end of Christmas. Its members are depicted from the front, but Millais has placed himself on a chair to the left, where he sits drawing on a pad balanced on his knee. The second or third youngest child, Emily, is the only person who acknowledges his presence – the others are concentrating on the elaborately crested cake on the table, but she is glancing sideways in an unconscious betrayal of the artist’s position. Millais seems to be looking at the figure of Fanny Lemprière, the ringletted young woman standing next to him, whom he was courting. The head of the family, Captain William Charles Lemprière, stands at the back of the group, while his wife is sitting on the right, absorbed in her knitting – her studious detachment a counterbalance to the sketching artist.

The tone is relaxed and intimate, for Millais was on good terms with the Lemprières. He lived in Jersey for the first nine years of his life and, according to his son and biographer J.G. Millais, spent a lot of time at Rozel Manor, home of Philip Raoul Lemprière, who ‘took a great fancy to him, making him ever welcome at the house… There, then, he spent much of his time, and… learned unconsciously to appreciate the beauties of Nature and Art.’ Raoul is said to have given the artist his first paintbox, and when he moved to London to continue his training as a painter, he became friends with Arthur and Harry Lemprière, two of the six sons of William Lemprière, brother of the seigneur of Rozel Manor. ‘We always called him Johnny, and he constantly spent the holidays with us at our home in Ewell, Surrey,’ said Arthur Lemprière, who later sat for The Huguenot 1852, one of Millais’s most famous paintings. ‘He always seemed to be sitting indoors, to have a pen, pencil, or brush in his hand, rattling off some amusing caricature or other drawing.’

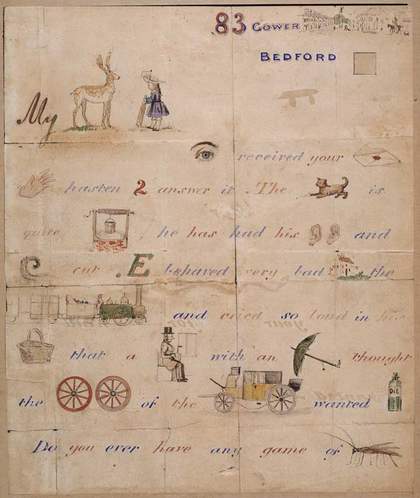

In 1840 Millais was admitted to the Royal Academy School in Trafalgar Square. He was eleven and a half years old, making him the youngest ever student, and three years later he sent the Lemprières the first of two illustrated letters that bear testimony to his precocious skills as a draughtsman. In the family address – 83 Gower Street – the word street is represented by two rows of houses bracketing a statue, with a man on horseback and a dog entering from the right. The letter continues the pattern of replacing words with drawings wherever possible. It’s addressed to Percy, the third youngest of the Lemprière children, who is shown as a little boy in a blue dress with a cricket bat in his hand and a feather in his hat. A beautifully rendered eye stands for ‘I’, a hand for ‘and’, a bee for ‘be’. Millais describes the antics of a dog obviously known to them all: he informs his friends that he has had his ears and tail cut, and that he behaved so badly on a train journey that a rather disdainful looking gentleman in a top hat and a tail coat thought the wheels of the carriage needed oiling. He sends his love in the form of a chubby cupid with drawn bow, and concludes with a message for Percy’s sister.

The letter is undated, but it must have been written in 1843, for in 1844, when Millais was fifteen years old, he repeated the exercise at greater length and in greater detail. The borders of his pages are garlanded with ivy, and there are jesters in the corners dressed in harlequin outfits. Christmas puddings serve as full stops. The letter is addressed to a group of ‘little dears’ – deer who are drinking at a pool of water – and illustrates the preparations for Christmas, with ‘boys going home to be merry and to enjoy the happy Season’. Geese and turkeys are pouring in from the country, and markets and farmers are sending pigs and cows to London butchers, who are depicted in the act of dismembering carcasses. The puppy reappears: he now begs and catches rabbits, and Millais reports that he recently pulled a cloth off a table and shattered some cups and saucers. ‘I can fancy you all [in] this cold weather talking about the garden wrapped up like little polar bears,’ he writes – though one of the animals is perched on its hind legs and looks more like a squirrel than a bear. He includes a drawing of Percy – ‘a modern armed young Briton’ – and predicts that he will challenge his brothers and sisters to ‘mortal combat’ when the snow comes. The family seems to have multiplied. There are now eighteen of them in all, shown sitting at the table in the final drawing, but even in such numbers, they will be hard pushed to get through the enormous Christmas pudding Captain Lemprière is cutting.

In the next two years Millais did more drawings of the Lemprières – one of the family in a pony and trap, two of Harriet and one of William – and on a visit to Jersey in 1845 he painted watercolour portraits of Philip Raoul Lemprière and his wife, and one of Rozel Manor. In 1846, when he was seventeen years old, he submitted his first entry to the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition, and in the same year sent two painted valentines to Fanny Lemprière. My mother’s cousin – who was also my grandfather’s god-daughter – owns one of them: Fanny is shown with her dark hair pinned up, sitting on a bench, while a man in a blue soldier’s uniform kneels beside her holding her hand. There is a brush of colour in her cheeks, and a pudgy pug dog lying beside her feet. Two cupids hover in the top corners, with bows drawn and darts pointing at the couple, but the man has already been struck: the arrow sticking out of his back testifies his devotion.

None of Millais’s biographers explains how their relationship ended, but Fanny makes a brief appearance five years later in the only diary the painter kept. He was staying close to Ewell, where he was painting the backgrounds for The Huguenot and Ophelia, and he met his ‘old flame’, on her way back from church:

I wished myself anywhere but there; all seemed so horribly changed, the girl I knew so well calling me ‘Mr Millais’ instead of ‘John’, and I addressing ‘Fanny’ as ‘Mrs B’. She married a man old enough to be her father; he trying to look the young man, with a light cane in his hand… an apparently stupid man, plain and bald, perfectly stupefied at Mrs B asking me to make a little sketch of her ugly old husband. They left, she making a bungling expression of gladness at having met me.

Detail from an illustrated letter by Sir John Everett Millais, Bt to the Lemprière family

Photo: Rod Tidnam, Tate photography © Courtesy private collection

His friendship with the Lemprières seemed to have run its course, but he must have been a regular visitor to the house in 1847, for in the course of the year he produced eight drawings and paintings of the family – two of Percy, one of Harry, Arthur and Emily, and four relating to Captain Lemprière and his career, as well as Twelfth Night. There are many copies of Twelfth Night in circulation among the descendants of the Lemprières. There seems to be some disagreement about which of the children is which, but my grandfather believed that the man standing at the back on the left, between Millais, Captain Lemprière and Fanny, was one of the two eldest boys. George Reid Lemprière later became a captain in the Royal Engineers and served in the Crimean peninsula. He married a woman called Jane Anderson and they had twelve children, including Kathleen Edith Lemprière, who married Henry Maingay in Scarborough in June 1902. My grandfather was the youngest of their two sons. In other words, George Lemprière was my grandfather’s grandfather – and, therefore, as significant a figure in his life as my grandfather was in mine. My connection with the Lemprières of Twelfth Night has always seemed tenuous in the extreme, and yet it takes only two steps to bridge the gap between the beginning of the twenty-first century, when my grandfather died, and the mid-nineteenth, when his grandfather sat for Millais.