David Campany

In the 1970s and 1980s many British artists, theorists and critics were engaged in some of the most advanced critical reflections on the social functions of photography in the world. The medium was given a root and branch rethink in an overhaul every bit as profound as the inter-war avantgardes that had dragged it out of the shadow of painterly pictorialism into new and vital roles suited to the challenges of the modern age. Conceptual artists of the late 1960s and early 1970s had opened up all manner of ways to deconstruct and re-imagine photography, and our expectations of it, although it would take another generation or two before those insights could really be felt. At the same time, the disciplines of art history and film theory were being revitalised by the new fields of semiotics, structuralism and psychoanalysis, and these rubbed off on photographic practice and theory. With the emergence of cultural studies in the polytechnics of the early 1970s, the value and effects of mass culture were put under the microscope, really for the first time. In society beyond, the print media that had made documentary photography and photojournalism such vital forces were being sidelined by television, sending them into a drawn out and painful tailspin.

Euan Duff

How We Are 1971

Front cover, photography book

© Courtesy Allen Lane/Penguin

Much of the advanced photographic art and writing of that time took as its primary subject, or more accurately its target, the photographic document and its status as evidence. It came under attack for everything, from its penchant for naïve realism and lumpen simplicity, to its sentimentalism, exoticism, class tourism and even voyeurism. Out of that attack came some of the most trenchant and iconoclastic art and writing that Britain has ever produced, from figures such as Jo Spence, John Stezaker, Yve Lomax, John Hilliard and Victor Burgin. (Interestingly, in this period Tate refused to collect photography by “photographers”, least of all documentarists, opting instead to acquire photographic images as they surfaced in Conceptualism, land art and performance art.)

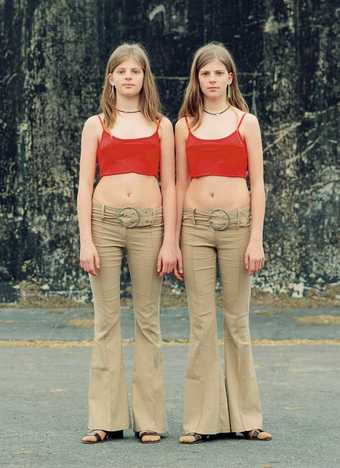

Albrecht Tübke

From Twins 2004

Courtesy Jochen Hempel

At first glance very little of this critical re-evaluation is evident in the photography selected for Tate’s new history of British photography, How We Are: Photographing Britain. Indeed, the period 1970–89 has been given the umbrella title ‘The Urge to Document’. The curation focuses on photographers who had that urge and doggedly pursued it, with or without an awareness of those critical currents beyond. Even so, one key upheaval of the era has had a huge impact on the shaping of this show. In fact, it informs the whole curatorial approach. It is the idea that popular and vernacular forms of culture are every bit as significant as high art.

Sarah Pickering

Flicks Nightclub 2004

From Public Order 2002–5

76 x 94 cm

© Courtesy Daniel Cooney Fine Art © the artist

One of the show’s curators, Val Williams, has become a notable force in British photography on just this basis. Her past shows have displayed discarded snapshots, long forgotten archives and anonymous functional documents alongside the works of named photographers, scrambling all hierarchies between high and low. She has favoured photographers who make humble documentation of the everyday (note the preference throughout the show for the unfussy centred compositions of the amateur and the catalogue photographer). Williams developed a quasi-ethnographic approach, seeking out practitioners and images that make use of the medium as an embedded form of local documentation and social exchange.

What happens when these forms of documentation are shown in an art gallery? Do they become art, as if the new context bestows a new value in the manner of Marcel Duchamp’s readymades? Not exactly. The effect is twofold. First, art tends to draw attention to the strategy or motivations behind the work, factors that are often overlooked when we encounter documents. The art context emphasises not just subject matter, but the various acts of choice that determine the image: the photographer’s choice, curatorial choice and viewers’ choices of interpretation. To show documents in the space of art does not simply elevate them, it always undoes them a little. What may have once been intended as objective now becomes estranged, oddly removed, and may even become an allegorical commentary on the very idea of the making of documents. This idea was one of the preoccupations of conceptual art.

So while the show sidesteps the direct inclusion of that ground-breaking conceptual work, its force is felt throughout. More than that, as we trace the projects here from the 1970s to the present, we can see a growing self consciousness, a growing internalisation of the insights of conceptualism. We see how photographers try to square the urge to document with an awareness of just how contradictory that urge can be – both ethically and aesthetically. We notice it first in the sudden appearance in the 1980s of the colour photographic tableaux of Martin Parr, Paul Reas, Anna Fox and others. This was photography attempting to document Britain’s consumer boom and its bitter underside, and it did it with thoroughly conceptual means. Out went the traditional notion of gritty, black-and-white uncomplicated realism, and in came an astute refunctioning of the gloss and obsession with surface beloved of 1980s lifestyle magazines. Here was the documentary photographer as image-savvy guerilla semiotician.

Contemporary audiences demand a great deal of images, both inside art and out. Paradoxically, this conceptualist reworking and estranging of the image turned out to be the key to documentary photography’s survival, particularly in art. As the exhibition moves from the 1980s to the present, this shift from traditional documentary into a self-reflexive quasi-ethnography becomes abundantly clear. Jason Evans, Nigel Shafran, Tom Hunter, Albrecht Tübke, Sarah Pickering, David Spero, Clare Strand, in fact just about all the young photographers who conclude the show are the offspring of two parents. One is the traditional documentary included here. The other is the conceptual art that is not.

Nigel Shafran

From Checkout portraits 2005

Digital inkjet print

41 x 31.7 cm

© Nigel Shafran 2007

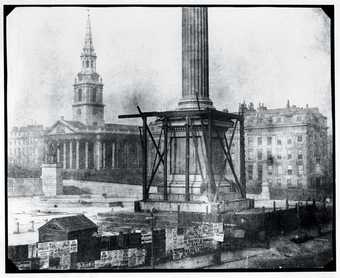

Nigel Shafran on William Henry Fox Talbot’s Nelson’s Column Under Construction, Trafalgar Square c.1843

Thoughts –

While I was standing on a litter bin taking a digital photograph of Trafalgar Square for reference, I began to think about the difference (in time and photographic process) between Fox Talbot taking his photograph – using a plate camera attached to a tripod with a long exposure - and the experience today of shooting a picture and viewing it seconds later. In looking at his photograph, I think about what hasn’t happened there yet and what isn’t there – it reminds me of now as then. And how uninhabited it seems. Maybe that was due to the long exposure time? I think of the protests, riots, rallies and celebrations that the square hasn’t yet seen, and all the people not yet there. I also wonder how close Fox Talbot was standing from where Monsieur de St Croix took his daguerreotype of Whitehall from Trafalgar Square four or five years previously, which is perhaps the earliest photograph taken in London. Thousands, perhaps millions, of photographs have been taken of Trafalgar Square since Fox Talbot was there – of loved ones and family, documenting their proof of being there.

William Henry Fox Talbot

Nelson’s Column Under Construction, Trafalgar Square c.1843

22.5 x 18.7cm

© Courtesy Science & Society Picture Library/NMeM

Nigel Shafran

Digital reference photograph of Trafalgar Square 2007

© Nigel Shafran 2007

Does the picture work like a sundial? Knowing the direction of the square, is it possible to tell the time when the negative was exposed by looking at the shadows of the scaffolding on the base of the column thrown by the winter sun? And is that hut on the left for the workmen?

Facts –

The picture was taken 38 years after Nelson defeated Napoleon at the Battle of Trafalgar. Apparently, the Nazi SS developed a secret plan to move Nelson’s Column to Berlin after the invasion of Britain during the Second World War. The lions that today sit around the column are said to have been recycled from the cannons of the French fleet. Their paws now at the foot of the column (not yet in place in the photograph) are reputed to have been modelled on dog paws as the artist and sculptor Sir Edwin Landseer had never seen a lion. For a short while in 1843 the statue of Nelson was exhibited on the ground, before its elevation to the summit of the column.

Likes –

Fox Talbot’s photograph feels modern. I like the way he has cropped Nelson on the top of his column out of the picture. I like the transient nature of the wooden scaffolding – the advertisements, posters and announcements on the temporary hoarding look the same as if they were knocked together today. How calm, tranquil and empty the place appears then.

Homer Sykes

When I was at college I came across the work of Sir Benjamin Stone. He was a Birmingham businessman at the turn of the century, and a Member of Parliament. However, his great passion was photography. He had made a remarkable study of traditional English festivals, ceremonies and customs as a hobby. I thought it would be interesting to re-photograph some of these customs – not in a static way with a large format camera, but in a way that fused my interest in American street photography (Lee Friedlander, Garry Winogrand and Burk Uzzle) along with the more traditional approach to documentary image making by people such as Cartier-Bresson and the other great Magnum photographers. I was primarily interested in recording the event, but I love the unplanned nature of this type of photography. Rather than just concentrate on the actual festivity, whenever possible I tried to include the unintended participants and to document the unfolding drama in a contemporary urban environment.

Homer Sykes

Caking Night, Dungworth, Yorkshire 1974

Silver gelatin print

40.6 x 50.8 cm

© Homer Sykes

Caking Night in Dungworth 1974 was shot in the Royal Hotel, Dungworth, Yorkshire, a small village on the outskirts of Sheffield. The “caking” usually took place on 1 November. (It was a local tradition associated with All Souls’ Day, where “soul cakes”were offered to poor Christian neighbours.) Competitors concealed their identity by wearing a mask or fancy dress, which by tradition had to be of local significance. Having paraded silently from lounge to public bar and back again so their voices didn’t give their identity away, the competitors went upstairs to be judged. In this picture the judging had taken place and one participant, still disguised, was supping a pint of beer through a straw. I liked the neat surreal nature of the disguise. His gloves contrasted with the couple in their woollen jumpers, slacks and pointy collars. Caking night no longer takes place.

I travelled all over the country to take these photographs over seven years, and covered about 100 traditional events. I tended to avoid folk club revival country customs, as they seemed to be more to do with town hall tourism than local history.

Homer Sykes

The Burry Man, South Queensferry, Lothian

Silver gelatin print

40.6 x 50.8 cm

Courtesy Homer Sykes

The Burry Man in South Queensferry 1971 was one of my favourite pictures from the series. In 1971 the local gravedigger John Hart was the Burry Man. He revelled in his annual day-long moment of fame and the £40 that he and his two assistants collected as they walked the town boundaries of South Queensferry, near Edinburgh. The origins of the custom are unclear, but this Green Man, covered in burrs (Arctium minus), is the remnants of an ancient fertility figure. There are nineteenth-century reports of similar Burry Men in other Scottish locations when the fishing harvest was failing. Now the event usually takes place during the second week in August, before the Ferry Fair. As part of my photographic record, I spent a couple of days with Hart and went out with him collecting the sticky burrs from a disused quarry. I photographed him making the patches of burrs for his costume, getting ready with his two assistants and adding the finishing touches of four roses to his front and four to his back, before he put on his pair of black boots.

Bacup, a small cotton milling town in the Pennines between Rochdale and Burnley, is the home of another traditional British custom that is very much alive. The Britannia Coconut Dancers, originally made up only of married men who worked at the Royal Britannia mill, used to perform around the town boundaries on Good Friday and Easter Saturday. In 1977 I photographed them on Easter Saturday. Again, their origins are obscure; some researchers believe they have a Moorish genesis. They have blackened faces and wear white caps, black breeches, red and white barrel skirts and black decorated clogs. Their name derives from the hard wooden discs, the tops of cotton bobbins, which are attached in three places: just above the knees, to their hands and to the waist. The dance is a series of jumps and leaps, and at the end of each phase the “coconuts” are struck together with a smooth circular movement of the arm in such a way as to produce a curious rippling sound.

Not all the pictures were taken in the countryside. In London’s East End I photographed a fortnightly custom called Farthing Bundles. At the turn of the century a number of settlements were formed in the poorest part of the capital, each sponsored by a school with the aim of alleviating distress and promoting awareness among the better off. The Fern Street settlement was founded in 1907 on behalf of the Devon’s Junior School in continuation of the personal effort begun in 1900 by the headmistress and warden Clara Grant. She started an imaginative scheme known as Farthing Bundles. Any child who had a farthing and could walk under an arch without stooping was given a small parcel of second-hand toys. The arch she had had made was inscribed: “Enter all ye children small, none can come that are too tall.” In 1901 it stood 48 inches high; by the time I made these photographs, it had been raised to 52 inches, and, with inflation, it was now a penny bundle. I particularly like the two young girls watching as their friends go under and collect their bundles. Their stance and manner seems to me to mimic their mothers having a natter, the way women used to do on street corners. The custom no longer takes place.

Martin Parr on John Hinde

In the mid-1980s I started collecting books with John Hinde’s photographs in them. The Small Canteen: How to Plan and Operate Modern Meal Service was the most elusive – it’s not under his name, but published under the auspices of the Empire Tea Bureau in 1947. I like pictures of food and the pastel colours, but what is great about this and his other work is that while the photographs were presumably commercial assignments, done from his London studio, he did them very well.

You can see that he was after the perfect picture, so that it would illustrate the subject, almost as a clichéd view. However, now they seem very modern despite the old look of the food - the colours that he used feel contemporary. I borrowed that palette myself, especially when I moved to taking pictures in colour in 1982. Hinde made Cabro prints, which is an incredibly elaborate and difficult process to get right. You have to do the three or four colours as separate layers, put together a bit like the silk-screen process. He used this method in several series, including his Women in War images. The prints are absolutely stunning. He was a pioneer of colour photography in the UK and would lecture at the Royal Photography Society about the latest developments in colour. You have to remember that, at the time, Britain was well behind America and Europe. Photographic Modernism didn’t really happen here, only in a sort of fleeting way.

John Hinde

Published in The Small Canteen: How to Plan and Operate Modern Meal Service 1947

© Courtesy RPS/NMeM/Science & Society Picture Library

It is extraordinary that Hinde is finally showing at Tate. When I first encountered him, his name was almost entirely forgotten – he was looked upon as the creator of clichéd postcards and almost a laughing stock. So I’m very happy to see this rather slow acceptance and understanding of his achievement. I think if he were alive, he’d be absolutely shocked that this work was on the walls of a gallery, because he would still look at it as a commercial assignment. Even I am still a little surprised at having my own photos hanging on Tate walls. I had been working for 30 years as a photographer before the Common Sense laser copies were first shown at Tate Britain in around 2001.

Martin Parr

ENGLAND. Garden Open Day from The Cost of Living 1986–9

Vintage C-Type, hand-printed 1989,

51 x 61cm

© Martin Parr/Magnum Photos

I guess that is how photographic culture shifts and changes as time passes. We think that everything’s been done, but, of course, there are many things that haven’t. In twenty years’ time we will be shocked by how certain works are perceived, and that’s exciting. The parameters shift. One of the recent changes is the acceptance of vernacular photography. John Hinde’s photography for The Small Canteen is a great example of that vernacular, because it wasn’t done to be great art. It was done simply to illustrate a book about canteens.

Anna Pavord on Charles Jones

Can a vegetable be heroic? In the hands of Charles Jones, yes – indubitably so. Jones was a professional gardener, born in 1866, the son of a Wolverhampton butcher. At some stage, and the maddening thing is that nobody yet knows exactly when, he bought a camera and started making portraits of carrots, cabbages, celery, marrows, radishes. These are valiant vegetables: bold, mighty, fearless and undaunted by the scrupulous gaze of one who knew them better than most. Set always against a plain backcloth, photographed head on, nothing distracts from the splendour of the subjects that Jones captured in his goldtoned gelatin silver prints. Were they specimens he had grown himself? Were they prize-winning fruit and vegetables (more rarely flowers) from his neighbours’ allotments, brought back in triumph from a local show to be immortalised for ever in print?

Jones died in 1959, having in his long life achieved just one moment of personal glory when the Gardeners’ Chronicle of 1905 commended his work as head gardener at Ote Hall, near Burgess Hill in Sussex. The magazine noted the beautiful herbaceous border he had made, stretching in a semicircle for several hundred feet round a lawn. It praised the well-trained fruit trees, admired the splendid tomatoes. Nowhere did it mention his skill as a photographer. That side of his life might have remained unknown but for a chance find in London’s Bermondsey Market. More than twenty years after Jones’s death, the photographic historian and collector Sean Sexton came across a trunkful of his prints there, about 500 of them, each named and initialled, but unfortunately not dated. None of the original glass negatives was with the prints, and none has yet come to light. Thanks to Sexton’s interest and care, Charles Jones is now recognised as a master of the camera as well as the kitchen garden.

Karl Blossfeldt, another plant portraitist, who made stunning silver prints of plants between 1900 and 1925, said he valued them as “totally artistic and architectural structures”. His interest in the plants he chose to photograph was driven by his professional interest in design. Jones is not like that. His photographs acknowledge and celebrate a gardener’s achievement: pride in a scab-free potato, the dignity of leeks with roots as sinuous as a sea anemone’s arms, a plump head of celery tied with a carefully trimmed knot. These are vegetables as prepared for a show bench: runner beans matched for length, onions skinned and buffed, turnips scrubbed and trimmed of their leaves. The long exposures used give the images the depth and serenity of a Dutch still life, an Adriaen Coorte.

Sexton believes, because of the technical method by which Jones produced his prints, that they were probably made between 1900 and 1910, while he was still head gardener at Ote Hall. After that he, his wife Harriet (the cook at Ote Hall) and their five children moved to Bourne in Lincolnshire. An analysis of the particular fruit and vegetables – celery “Standard Bearer”, potato “Midlothian Early”, apple “Ecklinville Seedling” – that appear in Jones’s images (he pencilled their names on the backs of his prints) might also help to date them. The netted musk melon “Suttons Superlative”, for instance, carefully displayed on one of its own large, rough leaves, was not introduced by Suttons until 1904, but stayed in its seed catalogue for the next twenty years.

Charles Jones’s youngest daughter, Kathleen, remembers that in Lincolnshire, her father no longer worked as a gardener, but took photographs for a living, advertising his services in the magazine Popular Gardening. From Kathleen, too, comes the poignant image of Jones’s precious glass plates, the original negatives from which he made his prints, propped up as makeshift cloches. In his Lincolnshire garden the ghostly spectres of onions past sheltered the emerging seedlings of onions present from the vicious east winds of the Fens.

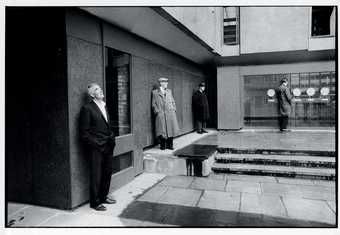

Viktor Kolár on Tony Ray-Jones’s The City, London 1967

Tom Ray-Jones

The City, London 1967

Photograph

17.6 x 26.2cm

© Courtesy Science & Society Picture Library/NMeM

Viktor Kolár

Palace Bonaventure at 5pm, Montreal, Canada 1972

Silver gelatin print

22 x 30cm

© Viktor Kolár

You can tell from Tony Ray-Jones’s photographs that he had a strong attachment to people, what we might call an empathy, and you can sense it in a picture such as The City, London. Maybe he picked this up on his travels around the US at a young age.

The pain and misery some of us go through can often result in creating the best photographs. It is when things are hard, I believe, that we may see what appears invisible, or appreciate the potential of a subject that looks ordinary. I recognise this quality in The City, London. It depicts a man finding shelter before a spring shower by the wall of a building. Sunbeams shine through the clouds and on to his face, which itself suggests an inner pleasure. He is on the left, but is the focus of the picture. The other men complement the space in a balanced way. You can look at this image from different angles and still not fully understand it – it has an ambivalence about it. The physical gap between the men is very revealing - as if he is recording the suppressed emotions in men who would like to be friendly with each other in such a public space.

I identify with this picture to such a degree that I tried to create a similar one, dealing with the same psychological dynamics, though this time based in Montreal. My photograph, Place Bonaventure at 5pm from 1972, was taken during the five years I lived there. I think that was the year that Tony died from leukaemia. Like his image, it focuses on an anonymous group of people. They are waiting for the bus home, and some of them already seem lost in a private, non-work world. I learned about Tony’s work when I saw his exhibition at the Optica Gallery in Montreal in 1972. Five years later I returned to Ostrava in what is now the Czech Republic. I had acquired a sharper eye. I now saw things other people did not seem to notice – small events or intimate situations in people’s lives – although some were too much to bear. You have to remember that I was living in the communist era. Here, I learned to develop a genuine respect for real situations that mattered to me – something that I feel I share with Tony Ray-Jones when I see his work. After all, I think we also shared a sense of optimism in the 1960s.

Kathryn Hughes on the Munby collection

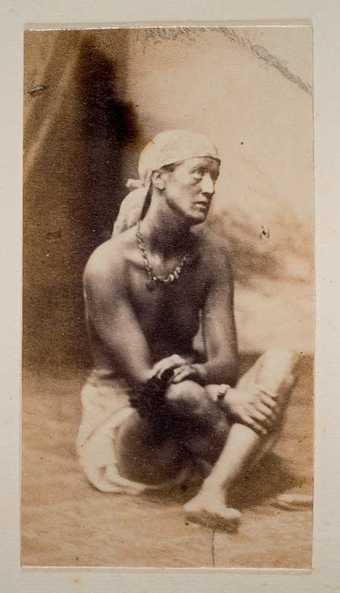

Hannah as a chimney sweep

Studio photograph commissioned by Arthur Munby of Hannah Cullwick early 1860s

© Courtesy the Master and Fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge

The Victorian period is chock-full of men who liked to talk and play and touch dirty. Mostly they did it the easy way – by picking up a whore on their way home from work. Others had a more complicated, anxious response to their desire to dally on the seamy side of the street. Gladstone tried to convert prostitutes by praying urgently with them. Dickens, meanwhile, was an intensely engaged supporter of Angela Burdett-Coutts’s home for “penitent Magdalens”, which aimed to turn fallen women into chastened – and chaste – seamstresses and maidservants.

For one man, however, the dirt in which he longed to roll was literal. Arthur Munby, a largely non-practising barrister of independent means, had a thing about very mucky women. The grubbier they were – as a result of working down a mine, mud larking on the riverbank, or simply dusting under beds – the more he liked it. For twenty-odd years Munby pursued dirty girls through the streets of the northern industrial cities and London, persuading them to return with him to a photographer’s studio where he arranged to have their pictures taken as they stood in their working clothes.

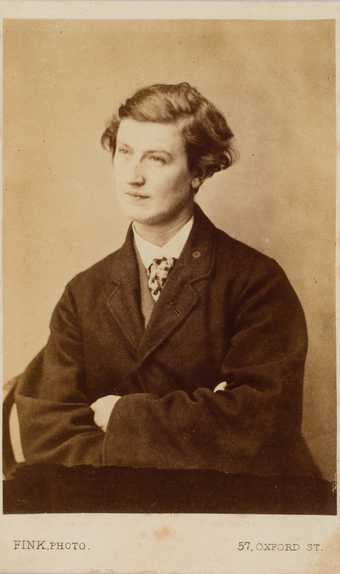

Hannah dressed in men’s clothes

Studio photograph commissioned by Arthur Munby of Hannah Cullwick early 1860s

© Courtesy the Master and Fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge

I had seen reproductions of these pictures before, principally in two excellent biographies of Munby by Derek Hudson and Diane Atkinson. Nothing, however, prepared me for the visceral shock of encountering the originals in the magnificent surroundings of the Wren Library at Trinity College, Cambridge (Munby bequeathed his vast collection to his alma mater). There are literally hundreds of pictures of hulking, raw-boned girls dressed in tattered trousers, hair bound up in a scarf, spades and brooms to hand. They stare out through the lens displaying little curiosity as to why this well-spoken, heavily bearded gent should have scooped them off the street and straight into a brightly-lit studio. And, really, why should they care? It is at least warm in the studio – a welcome relief from the harsh outdoors environment in which they normally spend up to twelve hours a day.What’s more, and perhaps most importantly, the kind gentleman has paid them for their time and seems to require nothing else – no fumble, not even a kiss – back.

Stranger yet are the notes that Munby has made on the back of some of the pictures. He was hugely excited by the notion that many of these girls were tall and well-built. Lovingly, he has recorded that one of them is a colossal (for Victorian times) 5ft 8ins. A bulging bicep clearly gets him going. And like an anthropologist encountering a new African tribe, he is fascinated by the way they speak. Snatches of their Lancashire and Geordie dialects are carefully noted on the back of the snaps.

Amidst these endless portraits of Betsy, Eliza and Ellen in the Wren Library, one face becomes more and more persistently present. It is that of Hannah Cullwick, the domestic servant with whom Munby had a relationship for 50 years and who he eventually married. Meeting in a London street in 1854 when he was 26 and she was 21, Munby and Cullwick embarked upon a relationship that was necessarily kept secret, even from his family. They had found their perfect match. The photographer was clearly aroused by Hannah’s large frame, capable arms and passion for scrubbing. She, in turn, loved her job and had absolutely no desire to jump the class divide and become a lady. On the one occasion when she took a relatively elevated situation as a cook, with a kitchen maid under her, she hated it. For Hannah, there was nothing better than the work of a skivvy.

Munby obsessively arranged to have Hannah photographed. As well as numerous pictures of her with a mop and bucket, he also persuaded her to pose as a chimney sweep. This involved her stripping off to virtually nothing and covering herself in coal dust (it’s apparent from other photographs in his collection that Munby was very turned on by black women). On another occasion she was staged as a slave, wearing chains, a persona which clearly excited them both, since Hannah took to calling him “massa”. Other photographs, however, show her in her Sunday best, decked out in a fine gown and, on one occasion, posed as if she were being painted by Gainsborough. Munby enjoyed the contrast of seeing his beloved Hannah dressed as a lady. She, however, hated it, finding the tight sleeves and long swishing skirts cumbersome and, in a strange way, demeaning.

No amount of seeing these photographs in reproduction, surrounded by carefully contextualising prose, can prepare you for the experience of viewing them naked and unadorned. The sheer volume of pictures in Munby’s collection shows the obsessive nature of his interest in working girls. The strange little notes on the back about their height and weight tell you that this interest goes unfathomably deep into his psyche. The growing preponderance of portraits of Hannah Cullwick speaks fondly of his real, but unlikely, love for her. But perhaps, most importantly of all, what these pictures demonstrate is a certain kind of innocence. Munby’s predilections may sound alarm bells in the twenty-first century, but in their own time they demonstrated a curiosity about how others lived which was as tender as it was unusual.

Brett Rogers on Madame Yevonde

The rediscovery of Madame Yevonde’s Goddesses happened at a time when artists such as Cindy Sherman emerged and the work of Claude Cahun was also being rediscovered - both of whom dealt with identity. I think that all Yevonde’s pictures were essentially about herself. Even her advertising work is about her own identity and the exploration her sexuality, which I came to the conclusion was, if not bisexual, then lesbian.

Madame Yevonde

Mrs Donald Ross as Europa (from the Goddess series) 1935

Vivex colour print

37 x 25.1cm

© Yevonde Portrait Archive

She was incredibly ahead of her time because of her use of colour. Looking at her work, it is hard to believe it was made in the 1930s. The colour is hyper-real and intense. Most people probably think it has been digitally manipulated; it has a very contemporary technological feel. She was, in fact, utilising the Vivex process, which was used only for a few years. It was very complicated, but she was fascinated by that whole technical side of how to make pictures.

She was also interested in earlier women photographers, including Juliet Margaret Cameron. As in Yevonde’s Goddesses series, there is a sacred and profane mythology running through Cameron’s work. Even the Madame Yevonde persona, which she used for commercial reasons, was created with one eye looking back to figures such as Cameron.

You also get the impression from her photographs that she had a really good time making them. There’s a lot of humour – certainly in the advertising work, she plays it up for all it’s worth. Sometimes it is tragi-comedy. And sometimes she is hinting at portentous things to come – the Second World War.

Tessa Codrington on Madame Yevonde

I was about twenty when I went to work in Madame Yevonde’s studio in 1966. She called herself Mrs Middleton, keeping her married name, and was Mrs M to us. The studio in Trevor Street, Chelsea, had a big skylight in the middle, and her desk was near the door. To me, she seemed as old as the hills, and came across as being very independently-minded and quite bossy. She was proud of having been a suffragette, and was definitely an early feminist, although the word had yet to become popular. She was brilliant with the patter when her sitters came to her studio, which is something that I learned from her when I started taking my own photographs.

Mrs M was always interested in the scientific and experimental side of her work. She liked doing solarised prints, a technique that creates white shadows and black highlights, and which Man Ray used to use. Even so, she never saw herself as an artist – to her, it was a profession just like a butcher or carpenter. She used this enormous camera that was as big as her. You focused by pushing the whole thing back and forth – it had wheels at the front.

When I was working with her she wanted to do an exhibition of famous women, so a few of them passed through the doors. On one occasion she booked Iris Murdoch for a sitting. She was also expecting her new cleaning lady earlier that morning. A bit before 10am, a little woman came in with a rain hat and umbrella. Mrs M immediately assumed it was the cleaner, and gave her a dustpan and brush and ordered her to get started, saying: “Be quick about it. I have an important visitor arriving.” Of course, she was talking to Iris Murdoch.

Jesse Landberg on Madame Yevonde

My first encounter with the work of Madame Yevonde was when I came across a tattered copy of the National Portrait Gallery exhibition catalogue hiding on the shelf of my local bookshop in New York. It was the dramatic name on the spine that got my initial interest, but once I saw the steely violet-green intensity of Medusa staring at me from the cover, I was amazed. It was everything I could ever hope to see in a photograph all crammed into one slick kaleidoscopic package – beautiful subjects, inspired colour palettes and, most importantly, a biting sense of dark humour that is as earnest as it is self-aware. I thought I had discovered the latest ingénue from a David LaChapelle shoot. but then I saw the dates beneath the plates. How had work this stylish, this fresh and relevant gone unnoticed? So much of Yevonde’s work transcends the confines of society portraiture, and in her truly subversive fashion she made sure these women outlived their earthly titles. Time has long forgotten Mrs Edward Mayer (sorry, love), but Medusa remains a true immortal, and a sitter, be it 1935 or 2007, couldn’t ask for anything more.