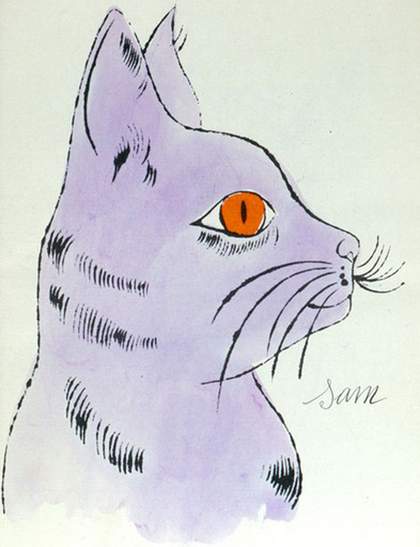

Andy Warhol

25 Cats Name Sam and One Blue Pussy 1954

Bound artist’s book with 36 plates (including cover)

Litho offset and hand-colouring

Courtesy Williams College of Art

© 2007 Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc /ARS, New York

It is twenty years since Andy Warhol’s death, and yet the interest in his life and work is as strong as ever.”Warhol” is possibly the strongest brand name in post-war art, and there is a flourishing industry of Warhol-related produce – books, stationery, urban daywear, screensavers, posters and period films. “Give people what they want,” said Andy, “That’s the secret of my success.” As well as the commercial industry his life and art created, there is his own collection, including the 612 Time Capsules – cardboard boxes filled with a random assortment of his daily debris – that he left for ravenous collectors, historians, PhD candidates and devotees to pick over. A glimpse of their contents was provided in the touring exhibition Andy Warhol’s Time Capsule 21, organised by the Andy Warhol Museum in 2003, which consisted of an eclectic mix of the personal and mundane – accountant’s bills, postcards, a pair of Clark Gable’s shoes, children’s books, greetings cards. A highlight of the show was the spooky reconstruction of Warhol’s mother’s bedroom. On one hand, there was something familiar about this set of keepsakes that included drawings from her grandchildren. On the other hand, the quantity of material, including a sizeable wardrobe filled with Julia Warhola’s hats, blouses, head scarves and prodigious collection of housedresses, pointed to a powerful maternal attachment.

As is well known, Andy lived with mom for most of his life, and this closeness generated its own Julia Warhola sub-industry. Today, you can read the private letters that homesick young Julia sent from Pittsburgh to family members back in the old country, at the Warhol Family Museum of Art near her home town in Medzilaborce, Slovakia. At http://edu.warhol.org/podcasts/julia.html you can listen to recordings of her singing the Carpatho-Rusyn folksongs of her childhood, which Andy had recorded on reel-to-reel tapes in the 1950s and early 1960s. You can use a computer font, FF Pepe, which re-creates her fanciful handwriting. In Ric Burns’s epic Andy Warhol: A Documentary Film (2006), the art critic Dave Hickey speaks of Julia’s “secret kitchen workshop” as more crucial in Warhol’s artistic training than, say, his understanding of Duchamp. The documentary also draws attention to his mother’s own artistry and the drawings she made, which curiously resemble the artist’s pre-Pop style. Warhol, in a late interview, claimed that his mother’s home-made art, fashioned from cut-out food cans, influenced the making of his own tinned art. Is such a revelation meaningful – or just another example of Warhol’s strategic self-mythologising? How should we assess his mother’s art? Of what value is her ambiguous presence, if any, in shedding light on her son’s work?

The answer varies between his commercial work and later Pop pieces. Julia’s hand is unmistakable in Warhol’s early art, if only for her distinct, stylised handwriting which graces most of the artist’s books, some advertising assignments and many drawings. Titles such as “Angkor Wat, Cambodia” and “Bangkok, Thailand”, written in Julia’s familiar scrawl, appear on the drawings Andy made on his round-the-world trip in summer 1956; it would seem that, curiously enough, the artist had his mother caption and sign these travel sketches back in New York, on his return home. The subject of their two twinned 1954 publications, Warhol’s 25 Cats Name Sam and One Blue Pussy and Holy Cats by Andy Warhol’s Mother (as Julia Warhola signed herself – submitting her identity to his), reflect their shared coexistence with a multitude of cats in a cramped East 75th Street apartment. But the differences between the artwork of mother and son are more illuminating than where they overlap. Julia’s story is about her beloved cat Hester, whereas Warhol’s collection of drawings has no traditional narrative structure, set, like his later films, in the ever unfolding present. Julia’s book is judgmental (some cats go to heaven, some do not), while here, as always, Warhol observes with a cool, objective eye. Finally, Julia’s stylised cats are removed from reality by wearing hats, sickly frowns and knowing smiles. Some defy gravity and anatomy by balancing on their tails. Andy’s are grounded, lifelike, foreshortened felines whose delicate outlines accurately and sensitively follow the true contours of the animal. His interest lies in an unembellished reality, never escapism.

The comical cherubs in Julia’s Holy Cats return, more slender and languid, in Andy’s In the Bottom of My Garden (c.1956). Evidently, by faking his mother’s “innocent” voice, spoken like a ventriloquist through her untutored handwriting with misspellings intact, the artist felt he could get away with a few lame double entendres regarding “pussy” and “bottom”. The frontispiece to Holy Cats includes another type of angel, a flat, winged creature in profile suggesting an annunciation, akin to Julia’s Drawing (Angel holding a cross) c.1957. These recall a Warhol drawing of a golden angel from the same period, and share the traditional profile pose, elaborate wing details and long flowing ringlets. As with the cats, however, Warhol’s figure is more solidly planted on the ground. Julia’s manic, looping, high-speed line, created directly in pen and ink, contrasts with Andy’s delicate, irregularly blotted edges. The difference in line quality brings home the fact that Warhol’s prodigious art making wasn’t fuelled by such nervous energy, but by some other steadier, more calculated sort of drive.

It is when Julia’s direct involvement exits and Andy turns Pop in the early 1960s that his mother’s presence is reintroduced in his art in a more insidious way. The hand-painted comic book characters in Dick Tracy and Saturday’s Popeye (both 1960) presumably recalled for Andy his childhood days when, as the artist claims, his mother read comic books to her bedridden son “in her thick Czechoslovakian accent”. Here, Warhol effectively translates her words back into American English. The cherubs proffering elaborate desserts in his Amy Vanderbilt’s Complete Cookbook 1961 may recall Julia’s innocents from Holy Cats; but Warhol eventually became bored with these tacky angels and towering profiterole cakes, and grew hungry for something more essential, more satisfying. He wanted to make gallery art, he wanted artistic recognition – and, it seems, he wanted a simple homely meal. Paradoxically, it was by abandoning the American aristocracy of the Vanderbilts and Manhattan socialites with whom he lunched, and turning to his immigrant mother’s kitchen that Warhol found America’s most authentic images of itself - the Campbell’s Soup cans, the Coke bottles, the Daily News, the dollar bills, the Brillo boxes. Warhol stumbled across “the real America” in the pantry of a woman who never adapted to the American way of life, or mastered the English language, or altered a peasant lifestyle which revolved around daily visits to the local food store. The signature repetitiousness in his work, habitually interpreted by art critics as, say, the “machine-like alienation of modern life in our media-saturated world”, was more a reflection of the sad routine of a lonely, elderly woman who pasted stamps into books, stacked soup cans in her cupboard, or collected returnable Coke bottles. In this same light, the arrangement of 32 Campbell’s Soup Cans 1961–2 is not necessarily another incarnation of the Modernist/Minimalist grid, as it is generally read, but also a kind of calendar, marking the daily task of feeding one’s family.

With his oddball, foreign mother miraculously reborn through his supermarket art as the typical US housewife, Warhol too could reinvent himself as the quintessential American son. Such an identity was absent in his childhood as a sickly boy growing up in an impoverished eastern-European ghetto in Pittsburgh. In going Pop, Warhol dropped what he saw as an old-fashioned idea of European sophistication. He abandoned the poetry and the opera, the suits and the bow ties, and put on a rejuvenated, all-American image – chewing gum, AM radio and giggling mischievousness - and modelled his new persona after the archetypical American boy. For a while, he looked like an overgrown Dennis the Menace – complete with the blue-and-white-striped shirt and floppy hair. To Warhol, the character of Dennis had everything he wanted: a slim American mom, eternal youth, fame and, from 1959 to 1963, a TV show.

Meanwhile, Julia Warhola, no longer asked to hand write the recipes and colophons of his pre-Pop work, and removed from her son’s daily working life, which had shifted from his home studio to The Factory, grew further away from Andy. She became more isolated, more reliant on alcohol and more invisible to those who knew him, despite roles in a couple of his more obscure films from the 1960s. When she became very frail around 1971, he sent her back to Pittsburgh, where she died about a year later. For the rest of his life Warhol claimed he suffered from guilt over those last months that they were apart.

The final, most direct, appearance of Mrs Warhol is in the remarkable posthumous portrait series Julia Warhola 1974. These are Warhol’s most intimate works. Gone are his acid colours, in favour of muddy, de Kooning-esque blurs of slate and a generally muted palette. Finger-painted (a rare technique for Warhol, though not unique around this time), they perform a gesture of touch bordering on sentimental kitsch, and suggest a brief return to the handpainted Pop style that he had so deliberately abandoned, to great success, in the early 1960s. He was at the height of his lucrative career as court painter to the stars, which makes Julia Warhola one of few uncommissioned portraits from this era. It is also unusual for the period in returning to the Warhol portrait’s original function as memorial, as were the first Marilyns – which he started within weeks of the star’s death, not almost two years later as he did with his mother’s posthumous portrait. Julia Warhola stands out by contradicting almost every innovation which made the artist’s paintings revolutionary: the impersonal choice of subject matter, the machine-like handling of paint, the art-for-money ethos, the absolute focus on the present. All these essential hallmarks are tossed aside. Warhol must have sensed the uniqueness of this series, given that he installed the pictures in their own isolated room at his ‘Portraits of the 70s’ exhibition at the Whitney Museum in 1979, away from the Jaggers, the Bischofbergers and the Maos of the main space. Julia didn’t fit with the rich and powerful in death any better than she had in life.

In 1963 Warhol made his second film, Sleep, in which his sleeping lover John Giorno is filmed for five hours and 21 minutes. It was, predictably, deemed unwatchable. Who could possibly endure watching someone sleep for so long? Well, a besotted lover, for one, pillow-gazing at this slumbering Adonis, or a mother admiring her children. Mrs Warhol, it is reported, watched Andy sleep, and liked to do so. Perhaps Sleep reproduces not just the mechanical gaze of the camera as it has been uniformly interpreted, but also its very opposite: an unflinching, loving gaze. Taken within the context of some of his other early films, such as Eat (1963), in which artist Robert Indiana slowly consumes a mushroom over 45 minutes, or Haircut (1963), these works seem almost to enact the attentions and early care of a mother, with her extreme interest in the ingestion of food, or the memorialisation of her baby’s first haircut.

There is a sad, prophetic irony in Sleep. Andy Warhol died 24 years later in 1987, one early morning in a private New York City hospital with no one to watch over him – adequately, lovingly, attentively, like an angel, or a lover, or a mother.