Thomas Gainsborough

Jonathan Buttall: The Blue Boy c.1770

Oil on canvas

179.4 x 123.8 cm

© Courtesy the Huntington Library, Art Collections and Botanical Gardens, San Marino, California

Upon its prize-winning appearance at the 1961 John Moores’ Exhibition in Liverpool, Peter Blake’s Self-Portrait with Badges 1961 rapidly became an icon of British Pop Art. It formed a full-page illustration to a feature on the artist as a “Pioneer of Pop Art” (along with Mary Quant’s clothes) in that innovatory medium of the period, the first Sunday Times colour section of 4 February 1962. The painting was a key prop in Ken Russell’s film Pop goes the Easel for the BBC arts programme Monitor, broadcast the following month, with Blake himself appearing to emerge from the picture. Tony Evans’s photograph the following year posed the artist next to the painting in the garden where the portrait is set, at the back of the studio he shared with Richard Smith in Chiswick, dressed in the same jeans and jacket.

Self-Portrait with Badges is a work fashioned from a rich range of influences, wearing its learning lightly. Melancholy rather than moody, the figure is steeped in the past, both personal and historical. Its denim garments form a fabric of vision with a rich texture of cultural memory.

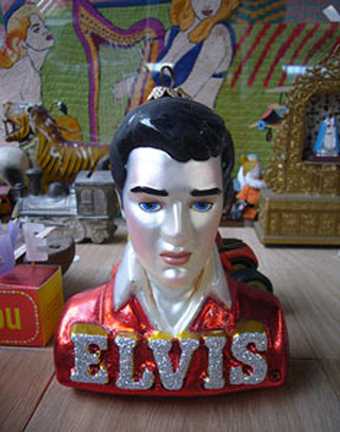

Elvis memorabilia in Peter Blake’s studio, 2007

Photo: Sam Messenger

From his earliest days as a student at Gravesend Technical College and School of Art, from 1946 to 1951, self-fashioning formed a key part of Blake’s life and work. He created various looks for himself, from painted ties under Fair Isle sweaters to the cut-down boiler suit he donned in imitation of the highly envied Levi jeans that a teacher brought back from the United States. Celebrated photographs of Jackson Pollock at work established turned-up jeans, denim jacket and baseball boots as the costume of choice for post-war art students. This was before most film and pop stars adopted the look, and may be seen to model studio portraits of Picasso in work-shirt and turned up trousers, as well as images of ranchers and miners in the American west.

Blake recalls picking up a denim jacket in the south of France in 1956 while on a Leverhulme scholarship studying folk art. Perhaps, as with so much denim wear in post-war Europe, it came from US army surplus. As such, it has a laconic echo of the garment he wears in Self-Portrait (In RAF Jacket) c.1952–3, which, combined with harlequin trousers, forms an outfit that portrays the casting off of two dismal years of National Service and the start of a brighter, more imaginative life as a student at the Royal College of Art.

Blake subsequently painted the jacket of Self-Portrait with Badges draped on a dummy and decorated – almost in a military sense – with badges and patches he collected, but did not actually wear. The evidently grown-up figure, bearded and balding (the artist was 29 at the time), adopts the diffident look of the heavily badged schoolboys he had portrayed in earlier paintings, with their anxious show of belonging to any number of clubs and causes, and standing in the way that children so often do for family snaps in the garden. Levi jeans were still scarce in Britain in 1961. They were not for sale in fashion shops, but largely found in work-wear and military surplus stores, often in highly irregular sizes. The figure sports prized 501s. He holds Elvis Monthly against the right thigh. The magazine saw the picture of Blake’s Self Portrait and responded by including the painting in one of their later issues. Blake subsequently wrote to, and thanked the magazine. The presence of the magazine is ironic, for Elvis abandoned wearing denim in public appearances in concerts and films. As was the same for many black musicians, denim was an uncomfortable reminder of the working clothes of a poor southern upbringing. This may well not have registered on British rock ‘n’ roll fans, for whom denim-clad Eddie Cochran was as exotically glamorous as the smoothly-draped Elvis.

Blake’s art of the period is sharply conscious of tradition, of both folk and fine art, and in Self-Portrait with Badges this is assimilated into the picture’s overall image. He was, for a time, taught at Gravesend by Enid Marx, who was famous for her textile designs and writings on English popular art, such as inn signs, ships’ figureheads and fairground paintings (the sort of artefacts Blake collected and sometimes displayed in his garden). In both its frontal pose and material texture, the subject of Self-Portrait with Badges bears something of this folk tradition, of carved effigies, straw dolls, paper cut-outs and earthenware figures. Added to this, the artist, in using the motif of the figure in the urban garden, acknowledges the influence of Carel Weight (who taught him at the Royal College of Art) and, in its stance and expression, Watteau’s Pierrot 1718–19, the famous portrait of a solitary, sad clown.

Peter Blake (centre back) during National Service

© Courtesy Peter Blake

However, there is another historic painterly connection worth a mention – Gainsborough’s Jonathan Buttall: The Blue Boy (c.1770). For much of the twentieth century this had proved to be something of a pop icon itself, reproduced on cheap ceramics and on toffee tins, beer trays and cigarette cards, and much parodied too, especially since its controversial sale to the Huntington collection in California in 1920, for which Cole Porter composed Blue Boy Blues. The Blue Boy was staged as an example of Gainsborough’s virtuosity in painting the fabrics of fine clothes, in this case of a cavalier costume, a studio prop, made in imitation of the clothes worn over a century earlier in the paintings of Van Dyck, and often used at fancy balls and masquerades of Gainsborough’s time. The satins and silks, the slashed sleeves and barely buttoned jacket emphasised a swaggering figure in a sweeping parkland setting. More restrained, Blake’s portrait is no less expressive, portraying denim as effectively as Gainsborough does satin, and in the tradition of pictures featuring men in fabrics which show everyday, sometimes workaday, activity, in particular a genre of mid-twentieth-century American realist art. In this, Blake has also been influenced by the portrayal of working men and women in the pictures of New Deal artists such as Ben Shahn, Bernard Perlin and Honoré Sharrer. Blake remembers being impressed by Shahn’s Pretty Girl Milking a Cow 1940, a painting of a solitary, muscular workman sitting under a tree playing a mouth organ (the title is the name of the tune he is playing), which he saw during the American artist’s UK exhibition in 1947. The accompanying book on Shahn focused on the musicality of many figures and how their stance and clothing, at work and play, revealed the social shaping of their human contour. “There’s a difference in the way a twelve-dollar coat wrinkles from the way a seventy-five-dollar coat wrinkles, and that has to be right,” Shahn declared. “It’s just as important aesthetically as the difference in the light of the Ile de France and the Brittany Coast. Maybe more important.” New Deal photographers (such as Walker Evans) and painters focused on the denim work-wear of the rural south, the folds and tears in the garments as much a sign of livelihood as those in the landscapes in which they laboured. In contrast to new synthetic fabrics of the time, which didn’t crease or fade, denim told a story in its very look, the life of the figure expressed in its fabric.

Peter Blake in his studio with his work He meets the Spice Girls and Elvis 2000–5 2007

Photo: Sam Messenger

Self-Portrait with Badges is a painting that looks both forward and back. While the figure is contemporary with, or rather in advance of popular fashion, it also looks back, in affection, to traditional times and places. The denim garments may be seen as an emblem of Peter Blake’s paintings at this time, which display the process of work, sometimes work in progress, in canvases that often show signs of age and wear. It is an art attentive to the fabric of appearances in the lived-in look of its figures.