CHRISTOPHER JONES: How did you meet Salvador Dalí,and what were the circumstances that led you to make the film, Impressions of Upper Mongolia?

JOSE MONTES BAQUER: In 1974 I was making a documentary in New York about audio-visual art in the USA. To familiarise myself with this work, I went to a video art conference entitled ‘Open Circuits, the Future of Television’ at the Museum of Modern Art. Later that evening, over dinner with some friends, we started a discussion about which artist it would be good to get involved in our film project, and we soon agreed it had to be the greatest one around – Salvador Dalí. Luckily, I was introduced to him by two ladies he held in great esteem, one of whom was an Italian princess, Vicky Alliata, who was taking part in the MoMA conference. Thanks to her, I received an appointment – at eleven minutes past eleven o’clock at the St Regis Hotel, New York, where Dalí had his winter quarters. He arrived very punctually, and warmly welcomed us in his dark, pinstriped suit. He led us to one of the salons he had rented on the lower floors of the hotel. But he couldn’t find the light switch. We entered the room, stumbling and bumping against furniture, until the artist, who was using his cane like a feeler to orientate himself, found a table, and suggested that we sit down to talk in the dark, as if it were the most normal thing in the world. I had barely said a few phrases, when shouting resonated in the gloom: “DA! – DA! – DALÍ!” And then in a more normal tone, he continued: “Dalí is a universal genius. For this reason, hundreds of people approach him daily to enrich themselves. But what they do not know is that Dalí, as well as being a universal genius, is also an intellectual vampire who enriches himself with all the people who come close to him.” At that point, the lights came on. One of his assistants had heard the shouting and flicked on the switch. Then Dalí took a pen from his pocket. It was plastic and ivory coloured with a copper band at the centre. He said: “In this clean and aseptic country, I have been observing how the urinals in the luxury restrooms of this hotel have acquired an entire range of rust colours through the interaction of the uric acid on the precious metals that are astounding. For this reason, I have been regularly urinating on the brass band of this pen over the past weeks to obtain the magnificent structures that you will find with your cameras and lenses. By simply looking at the band with my own eyes, I can see Dalí on the moon, or Dalí sipping coffee on the Champs Élysées. Take this magical object, work with it, and when you have an interesting result, come see me. If the result is good, we will make a film together.”

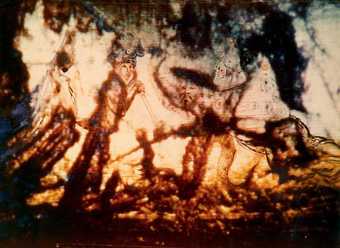

Film cell with images painted in by Salvador Dalí for Impressions of Upper Mongolia 1976

© WDR

Film cell with images painted in by Salvador Dalí for Impressions of Upper Mongolia 1976

© WDR

CHRISTOPHER JONES: How did you respond to that?

JOSE MONTES BAQUER: We decided to dedicate a full week to filming that corroded amalgam of copper and zinc. Amazing images began to appear – images similar to those obtained by satellites, on a scale of 1 x 500,000. Thanks to the blue and green lasers that we had set up, a fantastic geography of an imaginary planet had become visible. Remember that the satellite images of 30 years ago did not have the same definition that they do today. We filmed several rolls, which we then edited into a 30-minute summary. Then we took it to show to Dalí at the St Regis. As we set up our equipment, he puttered about the room whistling and humming. We watched the film in a hushed silence. At the end, we anxiously waited to see if our intense week on what felt like the edge of madness had made any sense to Dalí. Finally, he said: “It is not what I had expected. It is infinitely better. It is fantastic! We are going to make a film together.”

Jan Vermeer

Woman Reading a Letter 1662–3

Oil on canvas

46.5 x 39 cm

© Courtesy Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

CHRISTOPHER JONES: How would you describe the film?

JOSE MONTES BAQUER: Impressions cannot be compared with any other film made. Dalí chose the title. He believed that this homage to Roussel would be an important way to understand his work better. The open narrative structure is not easy, given that the beginnings and endings of the sequences have to be linked in a series that leads ultimately to a conclusion. The artist also told us that he wanted to paint over some of the frozen images of the film as a basic outline for a story that he would improvise as he commented on the resulting imagery. He invented the fable of a Princess of Mongolia from these partially abstract images. The story was: in ancestral times, in order to deal with a wave of starvation, the princess was forced to administer hallucinogenic powders from a gigantic soft mushroom to her subjects. This substance produced a collective madness among the inhabitants of her principality, who created rock paintings that were discovered on boulders by a Dalínian expedition to this dreamland.

CHRISTOPHER JONES: What was the connection between Dalí and Raymond Roussel?

JOSE MONTES BAQUER: They had corresponded briefly before the author’s suicide in 1933. In 1932 Roussel sent Dalí copies of his Locus Solus and Impressions d’Afrique. The artist replied by sending Roussel his film script for Babaouo. Several years later, Dalí painted a picture that he called Impressions of Africa. After the Second World War, Roussel’s works were rediscovered by Nouveau Roman authors such as Alain Robbe-Grillet. In their various analytical and biographical studies, they found numerous examples of words, and even entire phrases, with completely different meanings that were produced by a similarity in their sounds (so-called isophonics). The secretive and complicated writing system unleashed an automatism, which generated an entirely new sense to the phrase. From a psychological standpoint, this newmeaning, which was associated with the sound of a specific, written word, produced a change, or metamorphosis, in the imaginative meaning of the phrase. Roussel called his system the procédé, which became the basis of the double or multiple perceptions used by Dalí in his paintings and films. His system, which he named the paranoiac-critical method, was also based on metamorphosis.

CHRISTOPHER JONES: Could you describe some of these metamorphosis scenes from Impressions?

JOSE MONTES BAQUER: An example of what Dalí called a psychological image is the painting Woman Reading a Letter 1662–3 by the Dutch artist Jan Vermeer. On the wall behind a pregnant woman dressed in blue is a map of an undefined country. It is important to remember that the Dutch cultivated cartography in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries as an artform. Dalí said about the artist: “Mysterious geographic maps appear quite often in Vermeer’s backgrounds. The Dalínian paradox is to know how to distinguish the essential elements of this painting: the map, received from far away, which relates a sort of unimaginable fable, and behind the geographic possibilities, the fetishist verification that will permit travel to the imagined place.” Another important aspect of the film is the soundtrack. Dalí’s voice is accompanied by a musical montage with several recurring themes, including some pieces that were chosen and even mentioned by him in the film. For example, he presents Debussy’s Clair de Lune in his metamorphosis of a peaceful landscape into the portrait of Adolf Hitler. In one of the classic scenes in Impressions, Dalí is seen from behind painting Gala. The image exists as the painting Dalí from the Back Painting Gala from the Back Eternalised by Six Virtual Corneas Provisionally Reflected by Six Real Mirrors 1972–3. I remember that it was very difficult to light the live version without losing the character of the painting, which appears as an echo in the image. In this sequence, dedicated to Gala, Dalí whistles a theme from Richard Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde, which passes into a piano version of the music.

CHRISTOPHER JONES: Impressions was an extraordinary project, although it is not well known. What do you think is Dalí’s filmic legacy?

JOSE MONTES BAQUER: Salvador Dalí was a tireless, insatiable worker who had a marvellous spirit for collaboration. In such a complex project, his great culture and unacademic manner allowed him to connect well with specialists and technicians. He was generous with his time. During the filming, he never spoke of money. The only condition he stipulated in the contract was that a 35 mm copy of the film should be sent to the Dalí Museum in Figueres. In Impressions, he defined himself as an agent provocateur who acts in our brain to activate our fantasy. One of Dalí’s quotes is perhaps an appropriate message for all filmmakers: “The most decisive moment in the production of a film is when you need the force of will to convince your producers that if this film is not made, the world, as we know it, will come to an end.”