Towards the end of her book Divine Horsemen (1953), her passionate study of voodoo, the filmmaker Maya Deren describes how the goddess Erzulie descended on her and took possession of her in the course of a ritual ceremony in Haiti. When Deren decided to go to the island, her initial idea had been to stage a series of dances inspired by its rhythms and the religion of the islanders, but this plan was eclipsed almost immediately and a deeper involvement began. She stopped behaving like a distant, controlling auteur and impresario and became a participant. For this she has been criticised: yet her merging with the rituals completed the aesthetic fusion between film, art, dance and sacred ceremony that began with her experimental – “choreocinematic” - shorts made in the 1940s in New York and Los Angeles.

All in all, over the course of three visits, Deren spent eighteen months in Haiti between 1947 and 1952 and eventually accumulated 18,000 feet (5,486 metres) of film taken with her hand-held Bolex. The projected film was never made; after her death in 1961, her last husband, the composer Teijo Ito, and later his widow, Cherel, edited the footage in 1977 into the documentary Divine Horsemen: Living Gods of Haiti. The Itos’ film has been criticised for abandoning Deren’s highly innovatory, poetic cinematic aesthetic and making instead a kind of National Geographic documentary, unfolding to a didactic voiceover about the gods of voodoo (these taken from passages in Deren’s book). But this posthumous montage still reveals the hypnotic windings of her slow motion cinematography as she and her camera mingled with the entranced worshippers. Her images flare from over-exposure to the luminescence of the ritual’s symbolic white - the heat shimmer from the sea, the participants’ dresses, the death throe flutterings of the sacrificial birds, the offerings of flowers and flags and food radiate and blaze in the tropical light.

During a ceremony described at the end of her book, Erzulie began to “ride” Maya Deren. According to the erotic metaphor of voodoo possession, a deity “mounts” the entranced dancer as a rider seizes hold of a reluctant horse and overcomes the spirit of the animal (Zora Neale Hurston’s account of Haiti in 1937 is called Tell My Horse). “This is it!” writes Deren, as she evokes the dramatic scene when she became possessed. “Resting upon that leg I feel a strange numbness enter it from the earth itself and mount, within the very marrow of the bone, as slowly and richly as sap might mount the trunk of a tree. I say numbness, but that is inaccurate. To be precise,I must say what, even to me, is pure recollection, but not otherwise conceivable: I must call it a white darkness, its whiteness a glory, and its darkness, terror.”

Maya Deren in a still from Meshes of the Afternoon 1943

Black-and-white 16 mm film with sound

© Courtesy Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Centre, Boston University

A mystical oxymoron, this “white darkness” envelops Deren until she loses all consciousness of self: “The white darkness moves up the veins of my leg like a swift tide rising, rising; it is a great force which I cannot sustain or contain, which, surely, will burst my skin. It is too much, too bright, too white for me; this is its darkness.’Mercy!’ I scream within me. I hear it echoed by the voices, shrill and unearthly: ‘Erzulie!’ The bright darkness floods up through my body, reaches my head, engulfs me. I am sucked down and exploded upward at once. That is all.”

The pantheon of Haiti is “living” not because the gods and goddesses are immortals like classical deities, but because they are living archetypes, reincarnated during the rituals through the men and women they ride. Her own alter ego, Erzulie, is “above all, the Goddess of Love”, she explains, a voodoo Virgin Mary whose cult requires lavish offerings of perfume and flowers and even champagne from some of the poorest communities on earth; she is beautiful, sometimes tender, sometimes capricious, a diva, a femme fatale, “a Lady of Luxury”, a star. Those she possesses are made in her image, and move with her grace: “Her every gesture, movement of eyes and smile is a masterpiece of beguiling coquetry,” Deren explains.

Maya Deren’s narcissism remains throughout beguilingly unaware: she writes that Erzulie also manifests herself as “a cosmic tantrum” (and the filmmaker was well-known for her wilful, tough independence, which famously made her erupt). Such projection can’t help but make the reader smile. Deren was a legendary photogenic beauty, with a cloud of red hair, pale complexion and firm, rounded body, and the many celebrated photographs of her taken by Alexander Hammid, her second husband, show how carefully and well he had looked at the lighting and composition of André Kertész and Man Ray (like himself émigrés from central Europe). Deren was his Kiki de Montparnasse, and her self-fashioned charisma powerfully enhances her screen presence. Her “glamour” – to be taken in the strong sense of magic power – still inspires: in a recent issue of Strange Attractor, the writer and film historian Kevin Jackson ingeniously shuffles the letters of her name to come up with ten mystical anagrams (An Ayre Dame to Me Day Near).

Teiji and Cherel Ito

Divine Horsemen: The Living Gods of Haiti

Edited from Maya Deren’s original footage 1977

Black-and-white 16 mm film with sound

© Courtesy LUX

During the first half of the twentieth century, the quest for understanding of the interior structure of the psyche inspired the travels of anthropologists far and wide, and the various European concepts of the unconscious were profoundly shaped by contact with cultures in the non-West, which were perceived to be authentic, unadulterated, inspired and fertile. Artists and philosophers travelled with the ethnographers, sometimes in their armchairs, but sometimes not. Georges Bataille, Roger Caillois and Michel Leiris founded an institution – the Collège de Sociologie – in 1937 in Paris to study the sacred in different societies. Among these Haiti was pre-eminent, one of the most compelling sites of sacred arts. Furthermore, as a colony of France and more recently a protectorate of the United States, the island was less forbiddingly inaccessible geographically and socially than Borneo, Papua New Guinea, or other loci of Surrealist and primitivist curiosity. (Undercover Surrealism at the Hayward Gallery, London, last year, unfolded thoughtfully the fascination of Bataille and his friends in the journal Documents with the music, dances, masks and other aesthetic expression of non-European cultures).

Besides Hurston, several other go-betweens in the late 1930s and early 1940s reported from Haiti, exciting widespread curiosity in the United States and Europe: the maverick William B. Seabrook (The Magic Island, 1929) told of his experiences with priests and priestesses, the different trance states the rituals induced and the spells that could command the will and behaviour of others. Seabrook became friends with Man Ray and others in Surrealist circles, and his book inspired the early films about Caribbean cults and magic, such as White Zombie (1932). However, even more significantly for Deren’s career as a film-maker, the pioneering choreographer and dancer Katherine Dunham was creating a series of dramatic and highly popular shows focusing on the migration from Africa of the gods of voodoo, the vigour in the region’s rituals, their high octane potency and the richness of the accompanying arts. L’Ag’Ya (1938) staged a fight in a shanty town; Shango (1945) explored the old connection between the Caribbean and the faith of west Africa. During the most active period of Deren’s experimental film-making, she was working as Dunham’s publicist and PA, or general Girl Friday, and it was with the choreographer’s encouragement and contacts, and with backing from the Rockefeller Foundation (the first time such an award was given to creative work in the cinema), that she followed her to find inspiration in Haiti. Celluloid would capture permanently the exuberance and ecstasy Dunham’s dancers reproduced in theatrical performance and which, when they played in London in 1948, intoxicated the post-war audiences with their “speed and animal primitiveness”, as one critic wrote.

When Deren was working for Dunham, she was still in her twenties, and had already lived through different identities in various worlds: her family were refugees from the Ukraine, leaving Kiev when she was five; her father was a psychiatrist, and she went to school in Switzerland before settling in America. There she changed her name from Eleonora Derenkovsky, and took the name Maya, the Indian goddess of illusion. While on tour in California with the Dunham company in 1943, she began making Meshes of the Afternoon, an enigmatic and menacing dream of sexual knowledge in which she appears with her own double and her own double’s double. Apparitions of a flower, a knife, a key and a mirror (later broken) intensify the Surrealist dream symbolism of the piece. In several ways its theme echoes another cinema experiment of those years, Hans Richter’s botched but fascinating full-colour movie Dreams That Money Can Buy, which he began filming in New York in 1944. Dreams features Marcel Duchamp, as does a short called Witch’s Cradle, which Deren began making the same year (her first venture), filming the French artist in exile as he moved through Peggy Guggenheim’s gallery, The Art of This Century, in New York. This film initiated Deren’s weaving together of art, dance and magic significance; she called Guggenheim’s artworks “cabalistic symbols”.

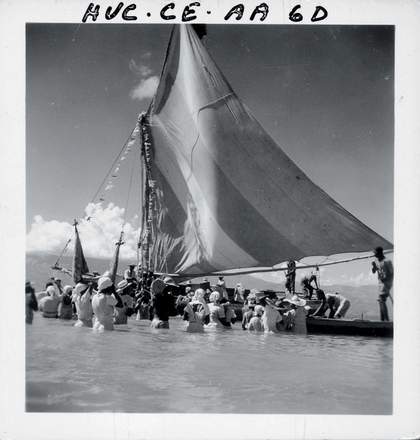

Maya Deren

Photograph possibly of a boat ceremony for Agwe, taken on one of her visits to Haiti 1947–52

Courtesy Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Centre, Boston University

Meshes is prized in the story of cinema, and its highly wrought aesthetic explores the full poetic and interior expressiveness of the medium through the signature elements of Deren’s film style: extreme angles of view, exquisite composition in high contrast of light and shadow, sensitivity to the texture and sheen of things, unabashed artifice in the editing to enhance the camera’s dance-like movements, enigmatic symbols in brooding close-up. Music is layered in to accompany the camera and heighten the sensual mood of foreboding, rather than identify effects of the action as a narrative. Above all, the action works back and forth over itself, accompanying the vagaries of obsession, feeling and memory, rather than unfolding in linear progress a plotted story. “Caught in Deren’s ‘mesh’,”writes Catherine Fowler, “time is frozen, replayed, remembered, reordered and foreshadowed.”Deren calls this “vertical” rather than “horizontal” time, and wrote a manifesto setting out her principles in An Anagram of Ideas on Art, Form and Film.

Katherine Dunham as Woman with a Cigar from the ballet Tropics

Photo: Alfredo Valenti

Courtesy The New York Public Library

Courtesy Southern Illinois University © The Estate & Legacy of Katharine Dunham

In the miniature (four minutes only) A Study in Choreography for Camera (1945), featuring Talley Beatty, a wiry male dancer from the Dunham troupe, Derenmanages some very adroit matching cuts to create visionary effects of soaring and weightlessness in a style that would eventually return full-blown in the colossal spectaculars of our time (Crouching Tiger,Hidden Dragon). For a shot set in a museum, Beatty spins so fast his head multiplies, echoing the triple-headed statue of Buddha behind him. A more complex film that followed, Ritual in Transfigured Time (1946), features another Dunham dancer, Rita Christiani, who had played in Meshes. Ritual fuses dance with cinema as a metaphor for the secret self in enigmatic relation to society: Deren stages a party as a kind of avant-garde reel of alienation, or an existentialist Strip the Willow, as Christiani weaves her way through a milling throng of party-goers and the camera moves with her.

Maya Deren was 44 when she died, possibly of a mixture of drugs and malnutrition (some claimed magic had something to do with it). Katherine Dunham survived her until last year – while Eartha Kitt, who is now in her eighties and was dancing in Dunham’s troupe in the 1940s, is throwing high kicks on the London stage as I write. In interviews, Dunham was sad that Deren herself and her posthumous cult have taken such small account of their productive alliance in the 1940s, and that instead Deren has been cast as a unique femme fatale, high priestess, muse and La Pasionaria of independent, experimental film. This image has generally succeeded in effacing the important artistic contexts which enfolded and fostered her - among which should feature the Afro-Caribbean dance movement led by Dunham.

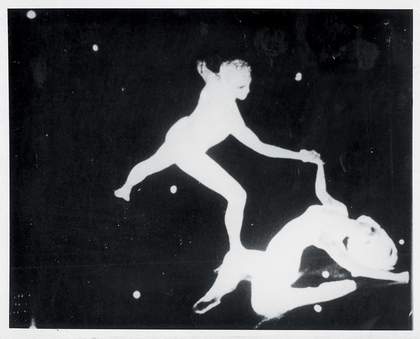

Maya Deren

The Very Eye of Night 1952–8

Film still

© Courtesy Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Centre, Boston University

Yet Deren’s self-fashioning does, however, have a genuine basis in one significant aspect: she realised the profound affinity between the material properties of film and inner states of the mind, including trance. She borrowed from the early “trick” films and magical entertainments of pioneers such as Georges Méliès, but she put the devices to use as mirrors of dream states, reverie and altered minds. Wipes and fades, matching cuts and negative stock, slow motion and blurred contours to the frame - all communicate very effectively the way thoughts and images come and go in “the movie-in-the-mind”, as António Damásio has called consciousness. In voodoo, Deren found an organised, collective stimulus to extreme mental states that already fascinated her. Unlike Hurston’s wary description of Haitian beliefs or the unleashed exuberance of Dunham and her performers, Deren’s camera spreads a “white darkness” on her subjects: by enhancing film’s qualities of spirit-like transparency, she etherealises the voodoo rites, turning the celebrants into angelically transparent luminous beings and the island into a paradise of light and air. There is no blood of sacrifice or squawking of the fowl as they are strangled: only the white feathers whirling, like cherubim.

The last film she completed, The Very Eye of Night (1952–8), picks up the metaphor of light in darkness, and gives it literal form. Working with the Metropolitan Ballet School and the choreographer Anthony Tudor, she blacked up the dancers, sheathed them in black costumes, and then shot them on negative stock against a white field, punctured with stars. The dancers are cast in an undeveloped Blakean cosmic plot; their movements are compelling as the ground disappears and they fly, white on black like silhouettes in reverse, unmoored by flesh or weight – Gnostic angels.

The making of The Very Eye of Night was beset with problems, and the film was not a success at the time. But its ambitions look very good now. It was included in the fascinating exhibition ‘The Expanded Eye’, held in the Kunsthaus, Zurich, last summer, as one of several kinetic and graphic experiments with film itself. Deren’s truth to materials and to medium as an artist using film has given her a crucial part to play at a time when the deceptions of realism have become an ethical issue as well as a stale aesthetic. “In film I can make the world dance,” she wrote; and she did.