Ernesto Neto

Hélio was the guy who managed to transcend Postmodernism and, as a visionary, to realise the most astonishing passage from classical Modernism to the volatile experience of present-day contemporaneity. Softly, yanking from the wall Mondrian’s colour and space, he embedded it in the body and handed it to the public. He camouflaged it in architecture, stormed the sociopolitical daily life, overfilled with sensoriality the gaseous image to emerge as a bólide (fireball) in the topology of history.His concepts of interactivity, coexistence and marginality are fundamental to what is happening now in art and in the world.

Marepe

My first experience of Hélio Oiticica’s art was from curators who found close relationships between my work, especially the Ambulantes (street sellers) series, and his. I was also familiar with the work of Lygia Clark and traditional Brazilian music (MPB – Música Popular Brasileira), and had contact with the Tropicalism movement, its concepts and its experimental character. I particularly like his Parangolés, the Bólides and Homenagem à Cara de Cavalo.

In Hélio’s time there was a need for the affirmation of our culture and the placement of social questions much closer to the public. Today, these questions are clearer and widespread. When he used the phrase “Seja marginal, seja herói” (“Be an outlaw, be a hero”), he wanted to make explicit the “marginal” universe. This universe now wishes to be seen as an integral part of the social one. I believe that, in a certain way, my work continues Oiticica’s through the affirmation of the popular universe (such as the ideas that were also part of the Tropicalism movement), and when I affirm the aesthetic of its inherent issues, including the African cultural heritage, matters of social classes, memory and family, always referring to the future and the past.

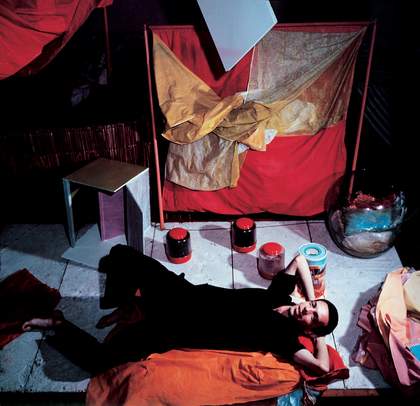

Catherine Yass

Descent 2002

16 mm film on projected DVD

Film still

Courtesy Alison Jacques Gallery © Catherine Yass

Catherine Yass

I first encountered Oiticica’s Bólides before I knew anything about him or his more performative art. His work communicates very directly with your senses. The colours function as form; some feel quite spatial, others quite solid. Some colours you sink into and some reflect back at you. It seems that he understood that really well, and in many cases they do more than illustrate the forms that they are on - they do their own thing.

I think his work is important because he manages to speak to, and play with, a veryWestern culture of Modernism and Minimalism, while at the same time referring to his own culture. Maybe they weren’t so different anyway, but he lets them work together, and that is a real achievement. I like the fact that his pieces feel handmade. In relation to the objects and materials that he put inside the Bólides, many of them were personal homages to specific people, which gives the work a generosity. Some of the boxes look as though they are made to move inside, although when they are in a museum nobody ever moves them, so I don’t know if you are meant to or not. Sometimes they will look like one thing from the outside, but when you peer inside they are very different. You can get very sophisticated dolls’ houses like that, where you don’t know if there is a room on the other side or not. His work suggests a little bit of that - mysterious spaces behind spaces.

In terms of my films, such as Descent and Flight, in which you see the images upside down or rotating, I try to create a framework where there is a space and a time where people can have their own thoughts. You can mentally wander around it and try things out, or make your own associations, your own memories. Oiticica is setting an equivalent frame with his work, in which you can play and maybe find something out about yourself. He never actually tells people what to think, and, through that, I believe he understood very well about how politics work. So his art functions like a form of micro-politics.

Chris Dercon

When I started working at PS1 in New York in 1987, it was decided to do an exhibition on Brazilian art, architecture and music, which got to be entitled Brazil Projects, (held in 1988) which included visual art, architecture, performance, television and music… not unlike the Tropicalism exhibit recently seen at the Barbican Art Gallery. We had amongst others been very impressed by Kynaston McShine’s 1970 MoMA exhibition Information, in which he looked far beyond Europe and America, and had included work by Cildo Mereiles and Hélio Oiticica. We travelled to Brazil, and in downtown Rio we visited the impressive Projeto Hélio Oiticica – the foundation that looked after his work and archive that was run by his family and friends. It is an incredible well kept, organized archive and gets even better by the year… On returning to New York, we decided we would dedicate an entire upper floor of PS1 to Oiticica’s Tropicalia installation as well as some Spatial Reliefs and Parangoles. For us, Oiticica’s work was not only a discovery but also a confrontation with our own lack of knowledge on him, his cultural context and the period. We invited Guy Brett to New York, who got to write a cover story for Art in America on Hélio, which surprised many.

A few years later in 1992 Luciano Figuereido, a close friend of Hélio and coordinator of the Projeto, Hélio’s brothers, Guy Brett , Catherine David, me and a few others put together the first retrospective of his work at the Witte de With centre for contemporary art in Rotterdam, which travelled around Europe including the Jeu de Paume in Paris, Tapies Foundation In Barcelona, and to the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis. The Dutch press was extremely unenthusiastic about the exhibition. They thought it laughable, old fart Brazilian hippy body art. I guess that exhibition came too early. However, it sparked an enormous amount of interest among international curators, art institutions and even some gallerists as Marian Goodman. The Projeto Hélio Oiticica was soon inundated with requests and letters. It started the Oiticica ball rolling.

As Oiticica conceived so many different propositions for art works or participatory works, the exhibition raised many questions about how to display his work adequately. As curators we had to ask – what do we do – ? Do you show the work as it was and allow the patina of age? Or do you clean , repair, reconstruct? How do you re-install a piece? What is the correct spatial interpretation of a work like Grand Nuclei? How far do you allow participation? To us it was important to consider these aspects seriously, as much of the material at that time was in poor condition, largely due to the effect of the Brazilian climate. We even organized an international workshop about this.

Where and how you install Oiticica’s work has a strong influence on how it is seen and experienced. Think of the White Chapel Eden experience.A perfect match, given the interesting symbiosis of a kind of upbeat but poor Brazilianess – so many Brazilian exiles came to London. The Oiticica exhibition in Houston was installed in the fabulous wing designed by Mies van der Rohe. It showed Oiticica’s radicalism in an unseen way, The combination of Hélio and Mies created a kind of spectacular ass well as highly didactic ‘ping-pong’ effect – communicating both with and against the architecture of Mies. Or a ping pong between two different kinds of modernisms.

One could immediately understand how Oiticica took a special place in the Modernist Movement as such. Along with other Brazilians like Oscar Niemeyer or Caetano Veloso, Oiticica had found a gap, created a hole within International Modernism – he had created a Brazilianness of Modernism, which was how to connect the local with the international. They did this through their interest in Brazilian nature, the popular arts and so on. Oiticica brought in a popular lyrical modernism (some call it Tropicalism Modernism). And this sense of connecting is why Hélio has been such an important influence on other artists – including Dominique Gonzales-Foerster, Pierre Huyghe, Liam Gillick and Rikrit Tiravanija.

One aspect about Oiticica that we didn’t research enough about at the time was to explore his numerous collaborative projects. I have met so many people – and still do – who said that they worked with him – graphic designers, artists, groupies, filmmakers. Oiticica was an itinerant urban dweller who left distinct traces wherever he went. It means that there is a lot of terrain left to cover.