I would have been eleven or twelve when I first saw the Jacobean double portrait known as The Cholmondeley Ladies c.1600–10. It hung just beyond the entrance hall of what is now Tate Britain, near the stairs to the loos – an enigmatic opener for the long march of the British School towards the glories of Turner and Constable. The two wintry revenants, propped elbow to elbow in bed with their glowing babies, made a deep impression. The blanched gorgeousness of their outfits, blooded by the hot royal red of the christening gowns, was part of it. So was the spooky incongruity of vivid faces looking out from the picture’s steam-ironed one-dimensionality, as though two people were standing behind it, sticking their heads through holes in the board. Mainly, though, it was their doubleness.

This is what makes every encounter with the Cholmondeley portrait so sharply defined, memorable and incomplete. The wallpaper repetition of the figures insists on parity, yet the faces demand attention because of their individuality (a word that didn’t enter English usage until the early seventeenth century, when this picture was painted). If you were to saw the panel in half, or if there were some kind of hierarchy – one figure larger, more central than the other, say – things would fall into place more easily. Instead, at the symmetrical centre, where the gaze wants to rest, there’s just a whitish crack between the pillows. Look either woman in the eye and the other becomes a restless peripheral presence, like someone anxious to edge into a conversation. The whole presentation is rigidly static but also unsettling, as both becomes either, either merges into between. It promises the aesthetic satisfactions of equilibrium but stirs up the disorientating tensions of duality.

The concept of symmetry – literally ‘commensurability’ – includes various ways of expressing the relation of parts (of bodies, buildings, pictures) to each other and to the whole. Though the word carries some prescriptive, academic baggage, it has since antiquity been part of the basic toolkit for explaining why certain visual configurations work the way they do. Symmetry perception is, it turns out, hard-wired in the human brain. This means that we register the presence of symmetrical features in our field of vision before we realise what we’re looking at. Since most living organisms and many natural objects are bilaterally symmetrical, symmetry perception probably has an evolutionary basis – you don’t want to stare too long or hard to make out the tiger’s eyes amid the tousled asymmetry of the foliage around them. Beyond the visual realm, symmetry shapes large areas of our experiential and cognitive universe. It translates into action and duration as pulse, mimesis, echo, rhythm. In cultural terms, symmetrical binaries structure almost every system of thought; they are often mythologised as twins – male and female, day and night, good and evil, life and death. All fields of intellectual analysis – philosophical, scientific, mathematical, political – make use of specialised notions of equilibrium and tension.

On the neuroscientific model, symmetry perception instantaneously triggers the recognition that something is there – something you need to respond to. But it’s the perception of subtle modulations and asymmetries that reveals exactly what, or who, you’re dealing with. ‘No two leaves of a fig tree are exactly alike,’ wrote Matisse in Jazz 1947, ‘they are all shaped differently. Yet each one shouts “Fig tree”.’ The print that follows this passage shows two curvy, cut-out ‘formes’, one in blue on white, the other white on blue. These forms – as alike and as different as two fig leaves – could, individually and out of context, represent upended vases or tree stumps, but together what they shout is ‘women’. Like Matisse’s paired The Tree of Life windows in the chapel at Venice or the clasping figures in his small bronze, Two Women 1907, they have almost the opposite effect of the Jacobean portrait. Instead of oscillating, hallucinatory dichotomy, they speak of the sensually and poetically complex pleasures of symmetry.

So integral are these pleasures to most attempts to make sense of the world that their opposite evokes feelings of dislocation, even fear. Any strongly asymmetrical shape gets called ‘strange’, in other words foreign or unrecognisable. The striking asymmetries in Romantic art, with its cult of rocks, storms, ‘unbalanced’ states of mind and impulsive actions, embody this strangeness. These are things that make you feel strange to, or take you out of, yourself (precisely the effect that the Sublime was supposed to have). The border between strangeness and recognition is neatly illustrated by the Rorschach blot exercise, in which shapeless ink spillages on a sheet of paper promptly metamorphose into bilaterally symmetrical forms (insects, flowers, faces and so on) when you fold the sheet in half. Warhol’s Rorschach experiments of the mid-1980s relate clearly to his obsession with copies and multiples, and the way in which these toy with the ‘recognition response’ as it applies to culturally constructed identity and commercial product recognition.

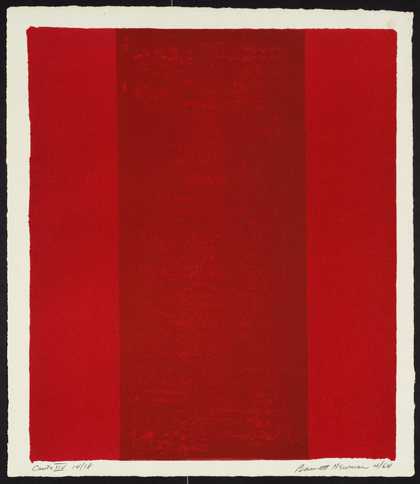

That so much twentieth-century avant-garde art lays heavy stress on symmetry – popularly considered a classical, conservative quality – partly has to do with the emphatic symmetries that prevail in industrial production, science and other non-fine art domains. The bilateral and rotational symmetries of Duchamp’s readymades – the snow shovel, bicycle wheel, bottle rack, urinal – simultaneously indicate their industrial origin and their upstart but impeccable claim to classical aesthetic credentials. Modernist formalism and the pragmatic aesthetics of commercial art both, for different reasons, want to activate the subliminal recognition response. In post-war American art, symmetry took on a further dimension. Barnett Newman’s absorption with the Genesis creation myth came to a head in his 1948 breakthrough painting Onement I. Behind the tightly channelled magma flow of the central cadmium red ‘zip’ lies biblical cosmology, in which, as the world is formed by God’s actions of making and dividing, the powerful binaries of male and female, good and evil emerge. The title Onement, from atonement or at-one-ment, is a sonorous pun on the idea of spiritual reconciliation.

Authoritarian ritual, commercial art and other visually coercive genres love putting symmetry in the frame because the recognition response overrides all others. Recognition doesn’t necessarily mean intellectual or moral acceptance, but it can feel guiltily like a step on the way. Images of atrocities are often a disquieting cocktail of alienation or horror and the mesmeric attractions of symmetry. The Isenheim Altarpiece, the Hiroshima mushroom cloud, the Twin Towers against a September blue sky – these universal signs for agony and carnage arouse aesthetic pleasure because they fit the way we’re wired to greet the visual, as though symmetrical formal relations were in some irresistible sense redemptive. If the visual image often seems to win the struggle for epistemological dominance, however, it’s important to remember that there are areas of experience impervious to visual codes. Pain, for example, or haptic pleasure; to the eye, the human body is bilaterally symmetrical, but to the blind touch it is something else.

Matisse carefully distinguished between the proportions that make a generic form recognisable and the uniqueness of a particular object, a quality that eludes all purely formal definitions: ‘The character of a face that has been drawn depends not on its varied proportions, but on a spiritual light that it reflects. So, two drawings of the same face can show the same character, even though the facial proportions of these two drawings might differ.’ If portraits are about the aura of identity, however, double portraits and figures often act, like the symmetrical sides of a doorway, to give entry to a situation, a story. You don’t ask ‘who is this?’ so much as ‘what is happening?’ And there’s hardly ever an answer that measures up to the visual effect of doubleness.

What’s going on, for example, between Gabrielle d’Estrees and Her Sister, the Duchesse de Villars – one nonchalantly tweaking the other’s nipple – painted in the late sixteenth century? Or in The Two Fridas, Kahlo’s 1939 double self-portrait, where the blood of one squirts into the other’s lacy lap? In Holbein’s The Ambassadors 1533, Hockney’s softly stagy 1970s portraits of gay couples, or the miniature of two Gujarati magnates kneeling on a flowery carpet in a kind of paradisiacal limbo, painted by Bishndas for the Mogul emperor Jahangir in around 1618, it is the situational atmosphere – puzzling and impossible to break into – rather than the sitters’ individual identities, that vibrates with faintly uneasy energy. Then there’s Picasso’s Girl Before a Mirror 1932. In a cocoon of curving outlines, Marie-Thérèse Walter looks at herself in an oval cheval glass. This image is often discussed in terms of the middle-aged artist’s erotic fulfilment with his new young partner. And it’s true – you feel this. But the doodling double profiles, circles and hatchings also encode a dreamy inwardness that excludes the male gaze, as the woman and her reflected double reach out towards each other. Their duality belongs to a nocturnal mirror world in which the reflected image disperses, rather than reinforces, all sense of individuality or oneness, making self-absorption, self-scrutiny and the suave arrival of the alter ego hard to prise apart.

Dame Barbara Hepworth

Two Forms (Divided Circle) (1969)

Tate

The word mirror is etymologically related to mirare (to gaze), and to miracle or wonder; behind these lies the Sanskrit smi, or smile. In this construction, reflection, wonderment and greeting are all components of the act of gazing. The self-containment of mirrored forms is given a different interpretation in Hepworth’s large bronze Two Forms (Divided Circle) from 1969, which, as you walk round it, ceases to be either circular or divided, as though two dancers were performing the solution to an equation. The party-piece primitivism of Brancusi’s various versions of his sculpture The Kiss echoes the cartoonish little fable of the origins of love recounted by Aristophanes in Plato’s Symposium. Humans, it seems, were once four-legged, two-headed spherical beings, who were sliced in half by Zeus. Our yearning for our severed halves is what causes ‘the love which restores to us our ancient state by attempting to weld two beings into one’. The asexual, invisible interiority of Brancusi’s stone kiss – like his idea of the dream within the sleeping head or the bird within the element of air – emphasises the inwardness or double nature of solid sculptural forms.

In his ‘conceit’ of lovers mirrored in each others’ eyes, the Metaphysical poet John Donne captured a trancelike bedroom fusion of intimacy and narcissism: ‘My face in thine eye, thine in mine appears/And true plain hearts doe in the faces rest.’ At the time Donne was writing and an unrecorded artist in Cheshire was painting The Cholmondeley Ladies, conceits were a way of thinking outside the box – you had to push through the intellectual scrum of an elaborate simile to find (if you were lucky) naked truth waiting on the other side.

Louise Bourgeois

Birth 1994

Drypoint on paper

23.6 x 18.2 cm

© Louise Bourgeois/VAGA, New York/DACS, London, 2004

In Donne’s poetry, sexual two-in-oneness takes the form of a pair of compasses, a hungry flea and the phoenix, among other things. The doubleness of the Cholmondeley portrait is, you realise, sexual too.

According to the story inscribed in its lower left-hand corner, the (otherwise unidentified) women were a living monument to coincidence – members of the same gentry family who shared the same birthday and wedding day, and gave birth at the same time. But coincidence is too abstract a basis for the image’s graphic strength; this is powered, rather, by a conceit on the theme of reproduction. The women, almost images of each other, have given birth to images of themselves, reproducing the pedigree line in which they take their place. Their marmoreal stillness (maybe they aren’t sitting up in bed but rising from a tomb?) recalls two cognate Shakespearean themes from the Sonnets: that having children is a means of ‘braving’ or confronting death, and that human experience can gain immortality by being mirrored in art.

The association of visual symmetry and sexuality or reproduction, the language of innumerable marriage portraits, has deep resonance beyond the purely formal. It resurfaces as a conceit – or what we now call a concept – in Damien Hirst’s Mother and Child, Divided 1993, where the sliced-in-half cow and calf, with their punning title, are a literal ‘anatomie’ (or dissection) of the maternal relationship. Louise Bourgeois’s 1994 print Birth from her Autobiographical Series is another example. The playing-card symmetry of the woman in labour and the child’s head emerging like a rival self between her legs gives a raw heraldic formality to the biological fact. The estrangement that exists between the world of the Cholmondeley portrait and our own can be felt in the painful ambivalence both these works express about childbirth. As Philip Larkin drily mused on his former room-mate’s fatherhood in Dockery and Son, reproduction can make you half, not twice, the person you were: ‘Why did he think adding meant increase? / To me it was dilution.’

Where ‘individuality’ once meant inseparability – the Latin term individuus could be used to describe friends or lovers – it now connotes personal identity, inviolable oneness. It is what sets us apart, not holds us together. The resolution of duality within the individual provides the core motif for the vast psychoanalytical literature that stems from Freud’s inference of conflicts between conscious and unconscious motivation and Jung’s dramatisation of the psychic landscape in the figures of anima and animus, the self and the shadow. At the opposite pole from the mystical, consummatory sense of two-in-one is our fear of the divided self. In Dostoevsky’s story The Double, the appearance of Mr Golyadkin’s Doppelgänger marks a personality in the final stages of disintegration, as the psychic auto-immune system turns on itself. While Golyadkin struggles to preserve the modest routines on which his self-esteem rests, his double, like a fiendishly competitive twin brother, knocks away every prop.

Roni Horn

Dead Owl 1998

Two Iris-printed photographs, ed. of 15

© Roni Horn

Why is the appearance of the Doppelgänger so terrifying while biological twinness is not? It asserts that the copy can steal the identity of the original. And if copies can be perfectly cloned, does the idea of the unique, authentic individual have any meaning at all? These questions were addressed, apropos of art rather than human genetics, by Walter Benjamin in his 1936 essay The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, which contains his haunting meditation on the ‘decay of the aura’ in modern mass culture. The aura, as Benjamin defines it, is a phenomenon associated with an original work’s ‘unique existence in the place where it happens to be’; it is, therefore, impossible to copy. For Benjamin the Marxist, photographic reproduction was good, because it ‘emancipates the work of art from its parasitical dependence on ritual’. But Benjamin the lover of art felt an overwhelming nostalgia for the aura; in the modern world, he wrote presciently, ‘the sight of immediate reality has become an orchid in the land of technology’.

This morning I’m looking at photographs of Brancusi’s lovers, Picasso’s girl, Newman’s hypnotic zip – and this seems quite a normal way to make judgments and comparisons, so long as you think of photographs of objects as providing visual stimuli or data but as otherwise inert. Not, at any rate, caught in the act of identity theft. Officially, the idea that objects reciprocate the viewer’s gaze is fanciful, although, as a child, this is exactly how I felt about the Cholmondeley foursome. Here, Leonardo da Vinci’s theory of vision (which he thought he had proved by setting up facing pairs of mirrors) is nearer the mark: ‘The air is full of an infinite number of images of the things which are distributed through it… I hold that the invisible powers of imagery in the eyes may project themselves to the objects as do the images of the objects to the eye.’

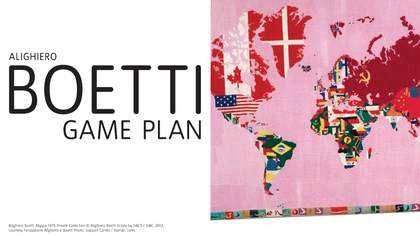

‘The air is full of images.’ Every work I’ve mentioned also exists as a digital image – a stream of units and zeros in cyberspace – whose infinitely self-replicating twins form and dissolve on my computer screen. They inhabit this medium entirely according to the conventions of visual display, including symmetry. But all conventions become wearisome, automatic, impossible to respond to, whereas uniqueness never does. In the technological context, the artistic use of multiple images becomes a classic framing device designed to rescue the unique individual from dispersion or sameness. Roni Horn’s book This Is Me, This Is You consists of two separate sets of 48 paired images of the same girl’s face, shot over a two-year period. You could get closer to a sense of the unique identity of a child you’ll never meet (not least because she is already four years older than her This Is Me self), but not much. ‘We’re all two people’ is the commonplace that the young Italian artist Alighiero e Boetti picked up and personalised in 1968 – like the cigarette filters, cardboard and bits of graph paper that went into his constructions – by adding ‘e’ (‘and’) between his first and second names. Wouldn’t it be nice, fantasised Boetti with throwaway arte povera delight, ‘to be two people – one all aware and real, the other all dreamy and unconscious – who go hand in hand, without ever mingling.’ Horn’s Dead Owl 1997 is two photographs of a stuffed snowy owl, hung side by side. Like The Cholmondeley Ladies, the dead owl and its double have a certain white imperious oddity – two brides at the same wedding, born, perhaps, the same day and trapped the same hour. Paradoxically, the Dead Owl’s duality is a token of its creaturely uniqueness, a reminder that it is the perception of difference, of the distance between things – the facing figures in the mirror or lovers’ eyes – that precedes (but only just) the ‘fearful symmetry’ of recognition.