Introduction

This report provides a perspective on the conservation of contemporary artworks and the challenges and possibilities that these works offer to the museum. It is divided into two parts. The first part will explore the development of conservation in relation to contemporary art, with a particular focus on the theoretical frameworks that have been used to explore the relationship between contemporary art, conservation and the museum. The second part considers the aims and scope of the project Reshaping the Collectible: When Artworks Live in the Museum, and proposes new perspectives on contemporary art conservation in response to the challenges presented by works of art that unfold over time; that question the boundaries between the archive, the record and the artwork; and that depend on social or technological networks that exist outside of the museum.

My perspective is influenced by my previous research, developed during my doctoral degree. Rooted in new materialist and feminist frameworks, this research focused on the ways that conservation and artworks contribute to the development of one another through their interactions.1 This previous research experience has contributed to my interest in exploring the connectivity in apparently distinct processes and practices, such as body and document, and performance and sculpture. As will become evident throughout this report, the research I will develop in the context of Reshaping the Collectible will focus on conceptual and material connections; namely, the ways in which people, structures and objects interact to produce and conserve artworks.

Conservation strategies are traditionally aligned to the maintenance of an artwork’s original material. With the incorporation of contemporary art into museum collections, expectations regarding the stability and longevity of artworks were challenged.2 Art forms such as kinetic art, conceptual art, performance and computer-based art that were prevalent in the twentieth century are at the core of what some scholars consider to be a paradigm change in the conservation of art.3 In light of the challenges presented by changing artistic practice, conservation’s traditional canons and strategies have required revision.4 This report will now move on to explore the development of theories and practices in the conservation of contemporary art since the 1980s,5 with specific reference to the preservation of time-based media and performance art.

A brief history of contemporary art conservation

In this section I will briefly examine the development of contemporary art conservation in general, and the development of time-based media conservation in particular, within Europe and North America. I will consider the role of conferences and networks as well as developments within and outside of the museum.

The emergence of contemporary art conservation as a field within Europe and North America can be traced back to the 1980s.6 The National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa, for example, hosted one of the first international conferences on the conservation of contemporary art in 1980,7 the same year that Heinz Althöfer published Moderne Kunst: Handbuch der Konservierung (Modern Art: A Handbook of Conservation).8 Yet the most significant growth in the field of contemporary art conservation took place in the 1990s. It was also in the mid-1990s that the specialism of time-based media art conservation started to be developed in Europe and in North America.9

Seminal conferences were held at this time that positioned and legitimised the field of contemporary art conservation, setting the research agenda for years to come. These include ‘From Marble to Chocolate: On 19th- and 20th-Century Art’ (Tate Gallery, London, 1995), ‘Modern Art: Who Cares?’ (Foundation for the Conservation of Modern Art (SBMK) and the Netherlands Institute for Cultural Heritage (ICN), Amsterdam, 1997) and ‘Mortality Immortality? A Conference of Contemporary Preservation Issues (Getty Conservation Institute (GCI), Los Angeles, 1998). These conferences and their related publications provide an overview of conservation’s response to contemporary art during the 1990s, but we can also see how they influenced the direction of future research.10 ‘Modern Art: Who Cares?’,11 for example, was the culmination of the project Conservation of Modern Art,12 which consisted of four years of interdisciplinary work around ten case studies. This project and the associated conference formed the basis for the foundation of the International Network for the Conservation of Contemporary Art (INCCA) in 1999; the network has since expanded, creating various affiliated and regional groups and gathering around one and a half thousand members.

Many of these early initiatives in the conservation of contemporary art were largely concerned with the preservation of ‘modern materials’.13 Similarly, early approaches to the preservation of media arts focused on the material challenges presented by film and tape. Interest in the preservation of video was primarily instigated by the broadcast and distribution industries, with some overlap with media arts.14 Media Alliance, a New York-based non-profit media arts membership organisation, hosted the first symposium on video preservation at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York in 1991.15 The Bay Area Video Coalition (BAVC) hosted ‘PLAYBACK 1996’, the first conference in which conservators were brought together with experts from all areas of the media arts.16 With the goal of understanding the challenges of ‘preserving the hundreds of thousands of hours of cultural and artistic history recorded on videotape’,17 this conference provided insights regarding the analysis, cleaning and remastering of video tapes, as well as regarding storage, ethical dilemmas, changes in technology (focused on digital video and its potential for the preservation of analogue video) and the conservation of installation art.18 The conference ‘How Durable is Video Art?’ (Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg, 1995) also opened up discussions about the preservation of video art, including issues of originality and authenticity.

Spaces for developing theory and communities of practice around the conservation of contemporary art started to multiply during the 1990s. This was seen in the Artists Documentation Program, which was set up by conservator Carol Mancusi-Ungaro and aimed to collect the voices of artists regarding their creative processes or, for example, their perceptions about the endurance of their works.19 Other important initiatives at this time that specifically focused on media preservation included the creation of the Electronic Media Group in 1997 by the American Institute of Conservation,20 and the foundation of the Independent Media Arts Preservation (IMAP) by Mona Jimenez and the Media Alliance by the end of the decade.21

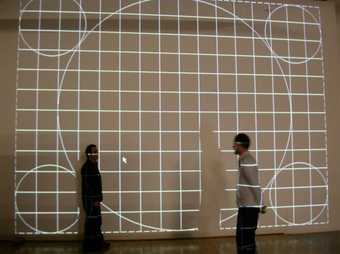

Fig.1

Roman Ondák

Good Feelings in Good Times 2003

Performance, people

Overall display dimensions variable

Tate T11940

© Roman Ondák

The new millennium saw an increase in the discourses surrounding the conservation of contemporary art, both outside and inside museum collections. Outside the museum realm, but undoubtedly influenced by its growing conservation needs, the first courses focused on training conservators for media22 and contemporary art started to emerge.23 Many modern and contemporary art museums supported in-house conservation departments from their inception, however these departments initially focused on painting conservation, with specialist paper, sculpture, installation, photography and time-based media conservation sections emerging later. The latter coincided with innovations in collecting practices within museums worldwide, including, most recently, the incorporation of software-based art and performance-based art. For example, 2003 marked the acquisition of the first software-based artwork by Tate (Michael Craig Martin, Becoming 2003, Tate T11812). Two years later, Tate acquired three live performance artworks – Good Feelings in Good Times 2003 by Roman Ondák (Tate T11940; fig.1), This is Propaganda 2002 by Tino Sehgal (Tate T12057) and Time 1970 by David Lamelas (Tate T12208). This made Tate the first collecting institution to acquire this artistic form.

In the late 1990s and the 2000s, funding streams such as those provided by the EU opened up opportunities to develop research into the conservation of new materials.24 Research projects on the preservation of contemporary art, and of time-based media art in particular, therefore arose at this time. Naturally, for projects related to the characterisation of new materials and their degradation, interdisciplinary research carried out by museums was (and still is) crucial for the development of the field. This was (and is) also true for projects related to time-based media art conservation, which exist at the intersection of media archiving, computer science, critical theory, philosophy, art theory and conservation.

While some of the research projects on time-based media and performance conservation were led by museums, either individually or as museum consortia, others were brought together through collaborative efforts with academia. The next section will provide a brief overview of a selection of these projects and symposia.

Research initiatives on the conservation of time-based media

One of the first projects in the conservation of time-based media and performance art was the Variable Media Initiative. This project was started in 1999 by Jon Ippolito, when he was Associate Curator of Media Arts at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York. The Variable Media Network then emerged in 2003 through a collaboration with the Daniel Langlois Foundation for Art Science and Technology in Montreal. The initiative and the network produced several publications, a glossary of terms, an exhibition, two conferences, and templates for interviewing artists about their work. They also proposed a framework for characterising the behaviour of contemporary artworks – ‘contained’, ‘installed’, ‘interactive’, ‘performed’25 – that remains relevant and has been used in projects such as the Digital Index of an Artwork’s Life (DIAL; 2018).26 The results of the Variable Media Initiative further influenced the field by forming the basis for the development of other projects, such as Archiving the Avant-Garde: Documenting and Preserving Variable Media Art (2001) and Documentation and Conservation of Media Arts Heritage (DOCAM; 2005).27 While the former provided a taxonomic matrix for archiving media art, the latter grew those concepts into tools and models that can be used for documenting and preserving ‘new media art’.28

These projects operated on the boundary between conservation and archival sciences or other related disciplines like computer science, and were crucial for understanding conservation as both a knowledge-making activity and a practice that is related to information management. The connection between conservation and archival sciences is also visible in the context of other projects, such as AktiveArchive (2000–8), a collaboration between Bern University of the Arts and the Swiss Institute for Art Research that focused on the conservation of ‘electronic media’ art.29 Other examples include Capturing Unstable Media, created and promoted by V2_ (Rotterdam) in 2003, which aimed at conserving and archiving ‘electronic art’.30 Areas of confluence between disciplines changed according to the nature of the challenge: for example, the broadcast industries contributed significantly to developments in the preservation of video; archival scientists developed tools and theory around archiving sound and the moving image; and new media communities have been a driving force in developing practice for archiving the internet, including internet art – as in the case of Rhizome.org, an online platform that has been preserving ‘networked’ art since 2004.31

The factors at Tate driving museum-initiated research into time-based media and performance conservation include the acquisition of increasing numbers of time-based media artworks; the recognition of the specific risks and vulnerabilities of these works; and the consolidation of emerging expertise derived from a developing body of experience within museums and collections, as well as from interactions with projects such as those discussed above. For instance, the development of practice in the conservation of digital artworks in institutions led to the project Digital Art Conservation in 2010, championed by the ZKM Center for Art and Media in Karlsruhe.32 Some of the most successful initiatives at the beginning of the millennium involved inter-institutional collaboration, as in the case of Matters in Media Art, a project launched in 2005 that aimed to build common ground between three museums – MoMA, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA) and Tate – and to develop guidelines for the care and preservation of time-based media art.33

One of the main considerations stemming from these projects lies in the importance of managing information, supporting ongoing professional development in the use of digital preservation tools,34 and recognising the infrastructures of care that work across the institution35 and expand beyond its walls. The need to expand the skill sets of people involved in conservation led to new areas of collaboration, for example with software engineers, as seen in the ongoing collaboration between the computer scientist Deena Engel and conservators Glenn Wharton and Joanna Philips.36 Similar interdisciplinary collaborations took place in research initiatives concerning the conservation of other forms of contemporary artistic practice, such as performance artworks. The project Collecting the Performative: A Research Network Examining Emerging Practice for Collecting and Conserving Performance-Based Art (2012–14) resulted from a collaboration between art institutions (Tate and the Van Abbemuseum) and academia (Maastricht University). The network held four specialist meetings that brought together artists, curators, conservators, archivists, choreographers and scholars to discuss how performance art intersects with dance, activism, theatre.37 Considered a pioneering project in the conservation of performance-based art in the field of museum studies and conservation,38 Collecting the Performative resulted in practical tools (such as The Live List)39 as well as relevant publications.40 Tate Conservation has continued to build on this research through the initiative Documentation and Conservation of Performance (2016–21) led by Louise Lawson. Through the work of the time-based media conservation team this project has developed practical tools (such as the Performance Specification and Activation Report) and terminology for the preservation of performance artworks.41 Both of these projects, and the knowledge accrued through years of working with time-based media artworks, are at the core of the ongoing development of strategies for the care of performance artworks at Tate that will in turn influence how we care for other forms of artistic practice in the museum.

Along with research projects, conferences and symposia on contemporary art conservation have provided opportunities for knowledge sharing among professionals, and have led to the publication of much of the significant literature in the field.42 The 2000s and 2010s have been particularly rich in terms of conferences and research events. Conferences often stem from research projects: for instance, ‘Preserving the Immaterial: A Conference on Variable Media’ (2001) and ‘Echoes of Art: Emulation as a Preservation Strategy’ (2004) were outcomes of the Variable Media Network, the work of the Daniel Langlois Foundation, DOCAM summits43 and research networks such as NeCCAR (Network for Conservation of Contemporary Art Research) and NACCA (New Approaches to the Conservation of Contemporary Art). NeCCAR organised the three conferences ‘Cultures of Conservation’, (Museo de Novecento, Milan, 2012), ‘Performing Documentation in the Conservation of Contemporary Art’ (in collaboration with the Documentação de Arte Contemporânea project; Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, Lisbon, 2013) and ‘Authenticity in Transition: Changing Practices in Contemporary Art Making and Conservation’ (Glasgow School of Art, 2014),44 while NACCA organised ‘Material Futures: Matter, Memory and Loss in Contemporary Art Production and Preservation’ (University of Glasgow, 2017), ‘From Different Perspectives to Common Grounds in Contemporary Art Conservation’ (Cologne University of Applied Sciences, 2018) and ‘Bridging the Gap: Theory and Practice in the Conservation of Contemporary Art’ (Maastricht University, 2019).45

Important conferences held independently from research projects include ‘TechArchaeology: A Symposium on Installation Art Preservation’ (SFMOMA, 2000); 46 ‘The Object in Transition: A Cross Disciplinary Conference on the Preservation and Study of Modern and Contemporary Art’ (GCI and the Getty Research Institute (GRI), Los Angeles, 2008); ‘Contemporary Art: Who Cares?’47 (Foundation for the Conservation of Modern Art and the Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands, Amsterdam, 2010) and ‘Media in Transition’ (GCI, GRI and Tate, London 2015).48 Other conferences form part of a series, such as the seminal symposia ‘Future Talks’ (first edition in 2009; now biennial), ‘TechFocus’ (first edition in 2010, with subsequent events in 2012 and 2015) and ‘Transformation of Digital Art’ (first edition in 2016; now annual).

The body of knowledge created by these projects, networks, research initiatives and events is at the core of the theory and practice of contemporary art conservation. In addition, museum-based projects foster the development of both theory and practice (mostly through practice-led research), which is essential in the field of conservation. Looking at the challenges that contemporary artworks pose to conservation when entering museum collections has led to the expansion of the theoretical foundations of conservation, such that they have developed from a focus on art history (as exemplified by the work of conservation-restoration theorist and art historian Cesare Brandi in the 1960s and 1970s)49 to a diversified set of approaches to the conservation of contemporary art. The next section will set out some of the main theoretical frameworks that have emerged from the study of contemporary artworks and their conservation.

Theoretical innovations

The advent of contemporary art forms and new artistic practices has led to the reformulation of what conservation is, how it transforms cultural objects, and the roles of conservators and other agents partaking in conservation activities. The way that conservation has adapted to these new artistic practices has been influenced by the theoretical work of conservators in so-called ‘traditional’ contexts, such as the conservation of paintings and works on paper (for example, Salvador Muñoz Viñas or Caroline Villers),50 ethnographic objects (including Miriam Clavir)51 and sculptural objects (for instance, Jonathan Ashley-Smith and Jonathan Kemp),52 and those working in preventative conservation (such as Jane Henderson and Joel Taylor),53 among others.54 However, the lineage of conservation theory since the 1980s demonstrates that the development of theoretical thinking in conservation has not emerged purely from these traditional fields, but has emerged across (and at the intersections between) a variety of specialisms.55

There are some aspects that make theoretical thought around the conservation of forms of contemporary cultural practice particularly generative. The changing nature of time-based media artworks and performance art is particularly useful when studying not only how conservation activities adapt to new forms of artistic creation, but also how changes in the understanding of conservation impact the way we address the possible futures of these artworks.

Conservators of contemporary art often work on the conservation of artworks while the artist who made them is alive. As a result, a single work or various editions of the same work can materially change in the hands of the artist, or else can be reframed by an artist’s estate after their death. In creating theoretical frameworks for understanding these works in the context of their conservation, there are some paradoxical questions that inevitably arise: how is it possible to care for an artwork that intentionally disappears? Is it possible to speak about reverse conservation treatments for artworks that are always changing?56 How can we manage the possibly divergent expectations of the artist and the artwork’s owner regarding the future of the work? How might conservation manage the evolving identities of an artwork? How might it account for the interactions that are at the core of the artwork’s materialisation?

Given the challenges presented by new forms of artistic practice, and the consequent need for innovation in conservation, those developing the field have also looked to other disciplines to gather fresh perspectives. Theoretical advancements in contemporary art conservation have stemmed from studies in the philosophy of music;57 the structuralist philosophy of literary theorist Gerard Genette;58 approaches to environmental conservation;59 frameworks from science and technology studies;60 new materialism;61 perspectives on organisational sciences and practice theory;62 and insights from continental philosophy.63

There are some specific theoretical frameworks that underpin Reshaping the Collectible and that are particularly useful for the perspectives I am exploring within the project. In examining the ways people, structures and objects interact to produce and conserve artworks, I am interested in frameworks that interrogate how artworks can be understood through their relationship with conservation, and how conservation activities play a role in remembering and transmitting artworks through processes of interaction.

Theoretical frameworks that explore the relationship between artworks and conservation are usually concerned with how works change over time and how conservation responds to that change. One such framework is that which considers the effect of conservation on an artwork’s authenticity. Drawing on the work of Nelson Goodman,64 conservator Pip Laurenson has brought Goodman’s concepts of autographic and allographic artworks into the discourse around authenticity for time-based media works of art. For Goodman, an artwork is either autographic, meaning that it is created through a one-stage process in which the moment of its creation is the same as that of its execution; or allographic, meaning that it is created through a two-stage process – firstly, a moment of conceptualisation, and secondly, a moment (or moments) of execution. One example would be a musical piece, which is created at one point in time and then performed – or executed – at subsequent points. The distinction between autographic, one-stage artworks and allographic, two-stage artworks consequently implies a need to rethink notions of authenticity and originality within conservation. For instance, the perspective that associates the preservation of the artwork’s original material to its authenticity does not make sense if an artwork’s existence can be divided into its conceptualisation (first stage) and the moment of its realisation(s) (second stage). The philosopher Renée van de Vall has further developed this idea by explaining that some artworks can change their status, moving from allographic to autographic and back again at different stages in their biography.65 In other words, what makes the artwork what it is can change with time.66 The possibility of the authenticity of artworks existing in flux has also been highlighted by Rebecca Gordon,67 Hanna Hölling68 and, later, by Brian Castriota, who drew on semiotics and linguistics to propose a theory of many centres of authenticity existing at the same time.69

Perspectives on artworks and change have also been brought to the fore in studies that present conservation as a social activity that materialises intangible values, namely by authors such as Erica Avrami70 and in my own research.71 Here it was suggested that conservation activities end up choosing one of many possible futures or even materialities of artworks: more than engaging with the materials of artworks, conservation can, therefore, be seen as an activity that materialises artworks in the world. As such, artworks that are intentionally allographic, to use Laurenson’s approach to the term, help us rethink not only what conservation is – its ontology – but also the ethical ramifications of a particular way of practicing conservation, the social nature of conservation, and what it does in the world.

The social turn in conservation was identified as such by the conservator and theorist Salvador Muñoz Viñas in 2005,72 and is characterised as the implication that conservation activities refer to many other agents and forms of operating inside and outside of the museum. As Muñoz Viñas points out, in identifying a ‘social turn’ he was highlighting developments within the field from the previous thirty-five years, pioneered by studies in ethnographic collections. In recent years conservators and theorists have reframed conservation as an activity concerned with the preservation of cultural heritage values as much as their material manifestations.73

Recent studies into the role of people, nature and technology – or human and non-human actors – in changing artworks have highlighted the lifecycle of artworks inside and outside the museum.74 One of the main arguments emerging from these studies is that changes to artworks are a product of the relations of many agents that impact the works in various ways and at different moments in their biography. An artwork’s ‘materiality’ – a term that refers both to the social experience, or understanding, of material culture and to the material relations that contribute to (and are influenced by) such experience – can then be framed as a product of the relations among the many agents that are in some way involved with the artwork at any given time, which suggests that conservation is neither neutral nor objective. To use the conservator and theorist Hanna Hölling’s words, it is possible to say that conservation has evolved past the idea of ‘prolong[ing] its objects’ material lives into the future’ and that the field ‘is now also seen as an engagement with materiality, rather than material – that is, engagement with the many specific factors that determine how objects’ identity and meaning are entangled with the aspects of time and space, the environment, ruling values, politics, economy, conventions, and culture’.75 Connecting conservation activities with the materiality of artworks and objects leads to a wider recognition of the contexts in which conservation takes place. It reveals the impact of conservation activities on an artwork’s materiality and on the social production of meaning. For instance, the act of removing a tainted varnish from a painting evidently prioritises the materiality of the paint over the materiality of the varnish. It is an act that impacts the social experience and understanding of the work, from the actual matter that is part of the painting, to the cultures of knowledge that give the painting meaning.

In line with this, the importance of the museum ecosystem, its policies and procedures, and the knowledge cultures that underpin practice and decision-making, are being researched in projects such as the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Innovative Training Network titled New Approaches in the Conservation of Contemporary Art (2016–19), led by Maastricht University, and in Reshaping the Collectible at Tate. Both projects are strongly influenced by social science perspectives on ‘practice theory’, which reflect the dynamic relationship between humans and structures in the creation of social situations and environments.76

Another innovation that has emerged from theoretical studies in the field is an awareness of the need to look at artworks and their conservation on a case-by-case basis.77 Although not new to the conservation practitioner, this ‘casuistic’ approach to conservation, advocated by Renée van de Vall,78 acknowledged the necessity to accommodate the variable nature of contemporary artworks and their changing and sometimes conflicting values, and to assess those values when considering treatment, with the help of precedents set by past case studies. Creating a corpus of case studies became one of the priorities in the field of contemporary art conservation. Research projects emerged in order to form frameworks that could serve as a basis for casuistic analysis79 (as in Practical Ethics) and for the application of reflexive practice in conservation activities.80 These were deemed particularly relevant in cases where the artwork’s realisation is dependent on social contexts or multiple agencies that are sometimes hard to pin down.

Despite these theoretical insights and practical innovations, contemporary artworks continue to challenge conservation, raising new questions regarding their care. These questions often relate to what the artwork is or can be, which is defined in a process of negotiation between several actors at the point of acquisition, including, naturally, the museum. The second part of this report outlines how I explore these ideas in the context of the Reshaping the Collectible project.

Reshaping the Collectible: A perspective in context

The project Reshaping the Collectible aims to develop new collection management and conservation models to inform how particularly challenging works of art might live and flourish within the museum. Time-based media artworks81 are a natural focus of the project, as they do not conform to traditional museum practices. This, of course, does not mean that other not-so-contemporary artworks, or artworks created in recent years using so-called ‘traditional’ media, do not change, or do not challenge the museum. Time-based media and performance artworks are, however, recognised as non-conformist. They have been described by sociologist of art Fernando Domínguez Rubio as ‘unruly’;82 they have social and technological dependencies, both internal and external; they unfold over time; and they tend to change in ways that the museum cannot control. In other words, although both ‘traditional’ media and time-based media artworks do change, for time-based media this arguably happens at a faster rate, and, in this sense, they cause more immediate changes to conservation activities and the context in which they are situated.83

Particular themes in the project proposal for Reshaping the Collectible resonate with my interest in new materialist and feminist theory that I developed during my doctoral studies. Within my research as part of Reshaping the Collectible I will apply key ideas from these fields to the realm of contemporary conservation practice. In particular, I will use the new materialist theory of ‘becoming’ to explore how artworks unfold in relation to their social dependencies.84 Conserving ‘unruly’ artworks implies understanding their social interactions, and mapping social behaviours that are essential for their ongoing materialisation, as well as understanding how they are remembered over time. Within my research, these factors are understood as a part of the process of ‘becoming’, and it is through this theoretical framework that I will analyse the connections between conservation and artworks, and how they reinforce or contest the practices of the museum.

I will apply this new materialist framework of ‘becoming’ to two key research strands: co-constitutive practices, and memory ecologies and the obsolescence of practice. In the first strand I will explore how the ideas of ‘becoming’ and ‘agency’ can be used to understand how artworks are ‘co-constituted’, which means how artworks influence conservation practice and how conservation practice impacts artworks. In the second strand I will use the concept of ‘memory ecologies’, defined as the connections between individual and collective memories,85 as a way of understanding how artworks and their social contexts are remembered and transmitted to the future. In this strand I will also introduce the idea of the ‘obsolescence of practice’ to describe the impact on an artwork of the demise of practices on which it may depend. My research in these two strands will be grounded in case studies of works in Tate’s collection, with the aim of drawing conclusions as to the implications of this theoretical framework for conservation practice.

This part of the present report begins by describing key aspects of the new materialist thinking that underpins my research, especially the theory of ‘becoming’. Following this is a discussion of my two main strands – co-constitutive practices, and memory ecologies and the obsolescence of practice – illustrated by examples of works from Tate’s collection. The report then offers some concluding thoughts on the ethical implications of the approach to conservation that I am researching.

A new materialist perspective

New materialism first emerged in the 1990s and is a growing field that encompasses multiple perspectives. Drawing on Marxist theories of labour and what has been considered a new wave of feminist studies, new materialist scholars reject binary ways of seeing the world. Suggesting that matter and discourse are intertwined, new materialism considers matter as a product of relations among human and non-human actors.86 Karen Barad, for example, proposes that we not only need to look at materials and bodies as matter, but also to understand that matter is always observed in a particular and subjective way.87 The ways that we observe matter, and the discourses that underpin that observation, change how we analyse and ‘measure’ it.88 In this sense, the ways that we observe matter contribute to its ongoing ‘becoming’. Imagine, for example, that a complex artwork that has both sculptural and performance elements is acquired by a museum. Because of its limited experience of performance art, this museum frames the work primarily as a sculpture, overlooking the features of the work related to performance. The performance aspects of this work may therefore fail to be activated when the work is displayed in the future and might be lost from the memory or history of the work.

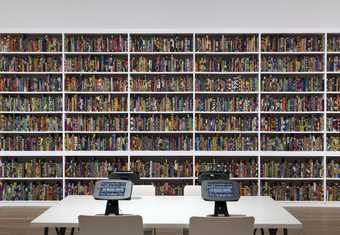

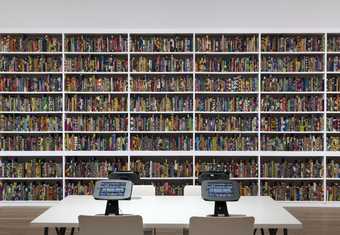

Fig.2

Yinka Shonibare

The British Library 2014

Tate T15250

© Yinka Shonibare. Co-commissioned by HOUSE 2014 and Brighton Festival. Courtesy the artist and Stephen Friedman Gallery, London

Drawing on Barad’s work, I approach forms of ‘becoming’ in my research by exploring how different framings or observations of an artwork impact conservation activities, and vice versa. In order to demonstrate the nature of this approach, it is useful to consider some examples from Tate’s collection. Yinka Shonibare’s The British Library 2014 (fig.2) is an example of a multifaceted work that requires an integrated approach which acknowledges its many material possibilities. The installation consists of 6,328 books individually covered by a ‘Dutch wax’ printed cotton textile. Printed on the spines of these books are the names of eminent first- and second-generation immigrants considered by the artist to have made important contributions to British culture. Other books have the names of vocal opponents of immigration printed on the same textile covers. An additional part of the installation is a study space with tablet computers, where visitors can access short biographies of the people whose names appear on the spines of the books, as well as their views on immigration. Visitors are invited to submit their own stories of immigration using the tablets and a selection of these responses is made available on a dedicated website.89

Standards and strategies for the care of this work need to consider its many forms, as it exists as a software-based artwork, a sculpture and a performative artwork at the same time. However, conservation strategies for these three aspects of the same work vary, and may oppose each other. For instance, preserving the material integrity of the sculptural element might involve placing some restraint on performative activities such as the physical interaction with members of the public or the handling of the books. Similarly, approaches to the conservation of the software-based elements might focus on the continued functionality of the interactive features of the work, resulting in cycles of upgrades for the software, but with no similar upgrades being appropriate or available for the installation’s sculptural aspects. In these ways, the artwork’s ‘becoming’ is a response to the various conservation strategies applied to it, while the nature of the work also determines those strategies itself.

The tension between the function of performative objects and the integrity of their sculptural components is also evident in works such as Kemang Wa Lehulere’s I cut my skin to liberate the splinter 2017 (T15274–T15279). This is a complex performance work comprising six sculptural elements with which six performers interact throughout the performance. The formal activation of this quasi-musical performance lasts around thirty minutes, and involves energetic interactions with the sculptures. However, the sculptures also exist as unique, independent objects.90 Should the artist wish to perform the work in the future or should it come into a museum collection, long-term strategies for the care of this work might involve reducing the frequency of the activations, or, for example, replacing some parts of the sculptural objects. Taking either of these approaches will help to consolidate a way of seeing the work, thus framing its becoming in the museum.

Co-constitutive practices: Becoming and agency

The process of becoming is, however, far from one-sided. From a new materialist perspective, it is possible to say that these processes of change are always developed through the relationship of all involved entities; they are co-constituted, meaning that artworks and conservation ‘co-become’, or become together. It is widely acknowledged within contemporary art conservation that artworks have a direct influence on the possible approaches to their care. For example, building on the work of the philosopher of music Stephen Davies,91 Pip Laurenson uses the idea that artists either ‘thickly’ or ‘thinly’ specify their works to think about how this might impact approaches to their conservation.92 Artists who ‘thickly’ specify their works are those who determine precise details of the installation of a work through instructions that fully determine how the work can be manifested, while artists who ‘thinly’ specify their artworks tend to be more open about how the artwork can be installed.93 In her paper from 2006, Laurenson responded to the types of time-based media artworks, in particular large video installations, that were entering Tate’s collection in the late 1990s, where artists such as Bill Viola, Gary Hill, Stan Douglas and James Coleman were very precisely (or thickly) specifying the details of the display of their work. For example, they attempted to fix the way in which audiences entered the space, its acoustics, the size of the images, and the technologies used for projections and playback, as well as the wall colours, lighting, carpet and acoustic panelling that would be used. Artists who thickly specify their works could, in this sense, appear to be hampering the becoming of their works. This process of becoming, however, can happen despite the pre-determined conditions existing in a given context. Guidelines, instructions and scores can be interpreted in different ways at different times. If a work is materialised in a very similar way on several different occasions, this accumulation of similar material instances of an artwork influences the way it will continue to be materialised over time, creating a precedent that can be referred back to by future conservators and curators.94 It is also true that creating the conditions for an artwork to be realised in a new form can shift the ecologies in which artworks change, disappear and persist, creating new material possibilities in the process.

In the artwork-conservation-museum relationship, artworks are not the only agent that goes through processes of ‘becoming’. Conservation and museums also ‘co-become’ with artworks and the contexts in which they live. In this project I will explore those practices of ‘co-becoming’ by responding to the relatively recent practice of collecting live performance-based artworks. Within this area of the project I will consider how such collecting might impact, and perhaps even reshape, conservation practice, and how artworks and conservation are co-constituted as a result.

The time-based media conservation team at Tate has been caring for performance artworks since the museum’s pioneering acquisition in 2005 of works by Roman Ondák, David Lamelas and Tino Sehgal, as mentioned above. Tate’s approach to the conservation of performance was developed in the years that followed by applying existing conservation practice by working to understand each artwork and considering the short- to long-term needs of each work. At this early stage, documentation strategies and templates that were employed for time-based media artworks more generally were used for the new performative works. This was the case with the ‘display specification’, a template commonly used at Tate to document the display characteristics of time-based media artworks such as digital and analogue media installations. This standard template was applied to performance works entering the collection; however, it was found that many such artworks diverged from the template’s requirements, and that a different form and narrative style was needed to capture the details of each specific performance.95 The increase in the number of live, complex performance works entering the collection, and the rise in loan requests for performance artworks owned by Tate, led to the development of an overall strategy for the conservation of performance art. This strategy includes a theoretical framework, documentation tools, workflows and media conservation strategies, and is regularly revised to adapt to the growing needs of the performance art collection at Tate.96

Analysing these practices of ‘becoming’ makes visible some of the ways that artworks and conservation constitute each other recursively. These practices of co-constitution not only change how artworks and conservation are seen, but they also change the practices of artists and conservators, among other agents.

The importance of discussions of this kind is well documented in studies carried out using feminist epistemology, which resist binary categories and male-centric and colonial forms of knowledge production. Feminist epistemology, explored by the likes of Barad and Donna Haraway,97 regards the production of knowledge as relational, situated in the individual, and therefore partial. Given the inherent partiality of conservation as a knowledge producing activity, it is also important to think about how it materialises ethically. What are we excluding when we see an artwork in a given way, from a particular perspective? What are the material possibilities of artworks and conservation that we are consolidating and denying through our decision-making processes? What forms of ‘becoming’ are we allowing to happen, and what possible futures are we excluding?

Looking at how artworks might ‘become’ through their interactions also implies the acknowledgement and study of those agents who interact with them, and the artworks’ own agencies. The term ‘agency’ refers to the capacity to do something that has consequences in a given context. I take this word to mean the explicit and implicit practices of agents that have consequences for the way things are seen, and the way things are or can be. The notion of agency is linked to an overarching understanding of relationships as being performative.98 Performativity is at the core of new materialist perspectives,99 which theorise that the connections between people and non-human agents, such as objects, nature, technology and infrastructures, have an impact on how reality is perceived and acted upon. Crucially, new materialist scholars100 recognise non-human agency to be on par with the agency of people.101

These perspectives are relevant for object-led practices like conservation. If we take the conservation of a painting as an example, relevant human agents include conservators, artists, curators and the public, all of whom might influence the artwork’s biography. The materials that make up the painting, including materials that were intentionally or unintentionally added during the life of the work, also influence the artwork’s biography.102 The characteristics of these materials (solubility and type of pigment, for example) define the range of options appropriate within conservation decision making. The conservation treatment amounts to the interaction between the painting, the conservators and their tools, and the museum structure and procedures, among other agents. In other words, the agency of materials is not dependent solely on their properties but is performed through a series of interactions.

Memory ecologies and the obsolescence of practice

Linked to the idea of the ‘becoming’ of an artwork is an awareness of how the activities of different agents will impact how a work is remembered over time. In my research, I am interested in how artworks that unfold over time are remembered, and how those ‘acts of memory’103 are performed through conservation activities. Through the notion of ‘memory ecologies’, I will explore how the ways in which people and non-human agents interact can impact how artworks are remembered. This involves exploring how artworks are created and transmitted, tracing forms of remembering them, examining how the artworks and their associated memories are transformed across time, and looking at how this impacts conservation.

Sociologist Andrew Hoskins defines the concept of ‘memory ecologies’ as a ‘holistic perspective for revealing and imagining memory’s multiple connections and functions’.104 The memory ecologies of artworks can co-exist and interfere with each other, bringing different histories to the fore. With this perspective, the museum goes beyond its role as an institution for collecting and preserving history and memory, and becomes recognisable as a memory ecology, operating within and feeding into other memory ecologies, built through the connections among the agents that sustain them.

Interactions among agents within different ecologies also contribute to the memory ecology of artworks and their transmission to the future. Another example of such ecologies is that of media ecologies – sets of interactions between agents that allow for the sustainability or obsolescence of specific media, such as file formats or 16 mm film. Like memory ecologies, media ecologies influence how artworks are and will be remembered and realised in the future. This is also true for practices that sustain a given way of performing in the world – such as the knowledge needed to dial a number on an analogue telephone. I will develop this idea, which I am calling the ‘obsolescence of practice’, in my research for Reshaping the Collectible.

Although the overarching idea behind the obsolescence of practice is yet to be systematically explored, it has been theorised in various ways by scholars in the social and human sciences, especially in the fields of decolonial theory in material culture,105 heritage studies,106 design,107 and media studies and the history of labour.108 I will attempt to explicate the idea more fully here through a brief discussion of three works in Tate’s collection that arguably depend on the maintenance of certain forms of practice – Tania Bruguera’s Tatlin’s Whisper #5 2008 (Tate T12989), Susan Hiller’s Monument 1980–1 (Tate T06902) and Cildo Meireles’s Insertions into Ideological Circuits: Coca-Cola Project 1970 (Tate T12328).

Fig.3

Tania Bruguera

Tatlin’s Whisper #5 2008

Performance, 2 people and 2 horses

Tate T12989

© Tania Bruguera

Bruguera’s Tatlin’s Whisper #5 (fig.3) consists of an action performed by policemen mounted on two horses – one of which is white, the other dark brown or black – that use crowd control techniques to direct members of the public within an exhibition space. The artist has set a number of conditions within the certificate for the artwork that need to be met in order to perform the work: the work must be performed by professional mounted policemen, in a place that has experienced social unrest, and where horses are used by the police in the control of crowds. Bruguera provides explicit instructions within her certificate of authenticity for Tatlin’s Whisper #5, stating that the methods of crowd control that are deployed within the performance must be current and recognisable to those who experience the work.109 Although the extinction of horses is unlikely in the near future, the same cannot be said of the practice of performing crowd-control operations on a horse. The obsolescence of this practice would undermine the performance of Tatlin’s Whispers #5 in its current form, and therefore conversations with the artist are underway to explore alternative forms the work might take in the future.

Fig.4

Cildo Meireles

Insertions into Ideological Circuits: Coca-Cola Project 1970

3 glass bottles, 3 metal caps, liquid and adhesive labels with text

Object, each: 250 × 60 × 60 mm

Tate T12328

© Cildo Meireles

Another artwork that would require the maintenance of an obsolete practice in order to continue to be performed is Meireles’s Insertions into Ideological Circuits: Coca-Cola Project (fig.4). With this work Meireles made use of economic circulation in disseminating political messages about US imperialism and consumerism in Brazil. To make it, the artist purchased Coca-Cola bottles and modified the messages on their glass surfaces, adding critical political statements such as ‘Yankees Go Home’, or even instructions for creating a Molotov cocktail using the bottle itself. After altering the bottles, Meireles would then return the bottles back to the economic system through a return-deposit system in place in Brazil at the time. The demise of this return-deposit system, however, means that the circulation of Coca-Cola bottles in this way can no longer happen.

The challenges faced by these artworks might mean that they evolve to be performed and experienced in different ways. This foregrounds the issue of how to track those changes in ways that contribute to the memory ecology for these works. One of the tools employed by conservation in creating institutional memory and contributing to the memory ecologies of the work is documentation. However, with artworks that rely on bodily practices for their activation, there are some aspects that are not possible to document.110 Acknowledging the limitations in what can be documented could also be the first step in exploring alternative forms for maintaining memory ecologies in the institution.

During the course of this project I will reflect on current processes of documentation for time-based media artworks at Tate. In addition to contributing to memory ecologies, documentation also has agency in how it influences the ways we look at artworks, and how it contributes to these artworks and their ‘becoming’. What we can document is only a part of what the artwork is and can become. As has been acknowledged in the field of contemporary art conservation,111 documentation is an endeavour that produces partial views of the work. This raises questions about what is included and excluded from documentation and creates a case for a more distributed approach to conservation. Through the frameworks of new materialism outlined above, this research strand will look at the agency of conservators and conservation documentation in the making of both works and institutional memory ecologies.

The ethical dimension

To conclude this report, I would like to emphasise a theme that runs through all that has been discussed above: that of conservation ethics. This is an important thread that I will explore throughout my research. I will focus on the ethical implications of making visible the social networks in which contemporary artworks are located, and of acknowledging the involvement of many different agents in their ‘becoming’. Discussions on this topic will need to address not only the ways in which we transmit artworks to future generations, but also what is transmitted and how the artworks and their associated human and non-human agencies produce or become part of memory ecologies.

An ethical approach to the ways we know things is at the core of theories of agency, such as Karen Barad’s philosophy, which underpins my work in the Reshaping the Collectible. As such theories suggest, the ability to respond to a work is dependent on our perspectives, on the ways we observe the artwork, and on how we act on that observation. As shown above, observations and responses entail inclusions and exclusions, such that privileging the idea of Shonibare’s The British Library as a sculpture, for instance, might render its website a static record rather than an interactive platform for stories about immigration. Identifying the exclusions and inclusions inherent to processes of conservation is therefore paramount in my research, as it allows us to move from binary views of objects and their care and to transcend disciplinary and political boundaries in conservation practice and ethics.

Recognising our partiality and situatedness is also essential if we are to move towards a process of knowledge production that acknowledges a variety of perspectives. In fostering multiple perspectives on what ethical conservation activities entail and in expanding the realm of conservation to include many other activities that are concerned with the care of artworks, I will draw on what the feminist, new materialist scholar Rosi Braidotti calls ‘affirmative ethics’.112 To use Braidotti’s words, affirmative ethics aims at ‘increasing one’s ability to relate to multiple others, in a productive and mutually enforcing manner, and creating a community that actualizes this ethical propensity’.113 I will explore this approach throughout my work in the project, and through ongoing collaborative discussion with both the Reshaping the Collectible project team and the time-based media conservation team.. From an ethical point of view, I propose that this integrated approach can help recognise as many different aspects of the artwork as possible, and help to acknowledge blind spots or exclusions in practices that impact artworks, their processes of becoming and how they are remembered.