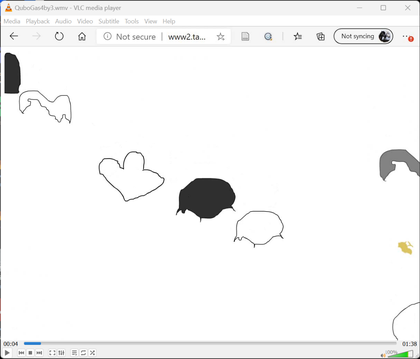

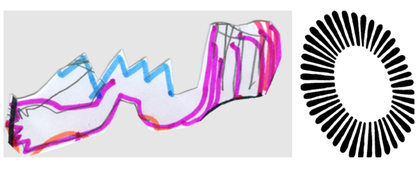

Watercouleur Park 2007 is an interactive animation made by the collective Qubo Gas. Using hand-drawn, coloured and painted abstract images, the collective created the artwork as ‘a stroll in our abstract universe, through our imaginary garden’.1 Watercouleur Park can no longer be accessed online. When it was launched, a new browser window would open and the work would spring to life.2 Scenes of cloud-like shapes, clusters of coloured doodles, organic forms and spinning cogs moved around the window, accompanied by a soundtrack of ambient electronic music (fig.1). There were fourteen ‘metaphorical landscapes’ in total, which appeared in a random order with short breaks between each one (figs.2 and 3).

Fig.1

Qubo Gas

Watercouleur Park 2007

Screenshot of the initial animation, from a video capture of the live site, prior to Flash becoming obsolete

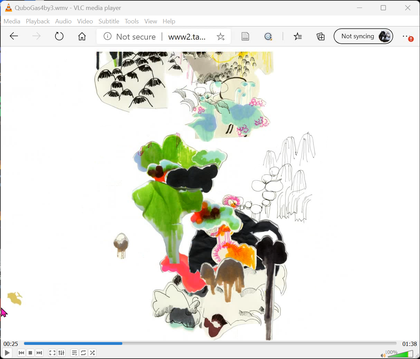

Fig.2

Qubo Gas

Watercouleur Park 2007

Screenshot of the first interactive sequence

Fig.3

Qubo Gas

Watercouleur Park 2007

Screenshot of the second interactive sequence

The animation could be interacted with, but it also had a life of its own. The cursor appeared on screen in the form of an abstract motif which the user could move around. Moving it allowed the user to highlight elements of the scene. Clicking on a shape could affect its movement, as well as trigger related audio elements. Otherwise the animation acted autonomously. If the viewer did not move the cursor, the animation took over and the shapes moved playfully around the screen. This reflects the collective’s interest in the idea of a ‘living microcosm… random happenings, natural processes, the weather, [and] lunar cycles’.3

The work stopped functioning online in December 2020, with the planned 'end of life' of Adobe Flash Player (Flash). It could be launched from the Net Art pages on the Tate website until May 2008, after which point it was linked to from the Intermedia Art project pages.4 It was contextualised through a description of the work, an essay by curator Bénédicte Ramade and a biography of the collective, all of which were moved to the Intermedia Art pages.5

Making and commissioning

The images in the artwork were drawn, coloured or painted by Qubo Gas members Jef Ablézot, Morgan Dimnet and Laura Henno. The work was developed ‘by hand, just like a story-board’.6 The images were then scanned and passed to programmer David Deraedt, who created the animation. The electronic music for the animation was created by Qubo Gas, DJ Elephant Power, Michael Mørkholt and Fan Club Orchestra. It combines sounds from computer gaming with acoustic guitar, slide whistle, synth, xylophone, voice and brass. Qubo Gas have described how they gave the musicians ‘free reign to compose what they wish[ed]’, but with some guidance around ‘tempo, rhythm, running time and emotions’.7 The music was combined with the animation, providing a sense of rhythm and playfulness to the forms on the screen.

Watercouleur Park was commissioned for Tate by Vincent Honoré, who was Assistant Curator at Tate between 2004 and 2007. The commission coincided with the inclusion of Qubo Gas’s work in the exhibition Momentary Momentum: Animated Drawings at Parasol Unit, London, co-curated by Ziba de Weck Ardalan and Laurence Dreyfus (3 March – 5 May 2007).

Reception and interpretation

In her essay ‘Kakemono’, Ramade connects the design and the movement of the work on screen to the Japanese tradition of kakemono (‘hanging thing’) scrolls, which were traditionally used to display painting and calligraphy.8 She also explores how the collective’s collaborative approach shares similarities with the subterranean plant stem structure of a rhizome, ‘from which a network of roots and aerial adventitious stems grows’, and which ‘is a moving process with neither beginning nor end’.9 Ramade’s essay notes the ‘flatness, the absolute rejection of any attempt at volume or depth’, which is characteristic of the work of Qubo Gas during the period.10

In a review of the commission for MAzine, Dave Miller connects the work to 1960s psychedelia, contemporary art and Pop art, describing it as a work of ‘random poetic arrangements’.11 Miller questions, however, whether Watercouleur Park can be considered an example of net art since other than the point of access – the website – it does not appear to require the internet. He also criticises the artist’s use of proprietary software: ‘I’m also disappointed in the use of Flash for the work, as my personal view is that net artists should be using open source software.’12

The artists’ practice

Jef Ablézot, Morgan Dimnet and Laura Henno formed Qubo Gas in 2000 after finishing their studies in Fine Arts at the Université de Lille. The name is a nonsense phrase the group created by playing with words. They worked initially with electronic music, creating ‘video clips, animations and illustrations for bands’ such as DAT Politics and Scratch Pet Land.13 In 2001, they performed the artwork Baover Tit at NetMage festival in Bologna.14 A ‘whimsical and fanciful world where magic mushrooms and multi-coloured ferns seem to be the only master on board’, Baover Tit was created as a hand-drawn animation in five chapters and experienced as a projection.15 Between 2003 and 2005, Qubo Gas were in residence at Fresnoy, Studio des Arts Contemporains in Tourcoing, which enabled them to develop more ambitious digital work and increased the collective’s visibility.16 In 2004, they created Uki-yo, a digital landscape that ‘evolves in a continuous and autonomous way according to a poetic algorithm’.17 This was shown as a projection onto glass at Parasol Unit, London, in 2007, the same year that Watercouleur Park launched on Tate’s website.

The collective has described how, when they were starting out, very few artists had a website or made art for the internet.18 Seeing the potential of working online, in 2000 they set up an interactive website with programmer David Deraedt, where they experimented with animation using Flash. They described how ‘everything was a bit shaky, low-fi and naïve’, a quality that suited the simple, hand-drawn nature of their work.19 Between 2000 and 2010, the majority of their artworks were created and distributed online. Since then, they have worked less regularly with online or digital creation and now focus on craft and making.

Technical narrative

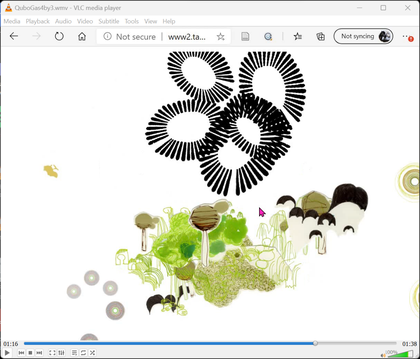

Fig.4

Screenshot of Watercouleur Park, with the ‘cursor’ image at the bottom right (indicated by a pink arrow)

In its functional state, when a user opens the link for Watercouleur Park an interactive Flash application is automatically launched.20 The animated graphic elements scale to fill the size of the user’s browser window. Before the main interactive graphic and audio elements load, a set of simple outlined shapes pass across the screen. These shapes are non-interactive and allow for the variable loading time required for the animation to start, which is dependent on the user’s connection speed. From the start, the cursor is a yellow irregular shape (fig.4), following the user’s mouse movements as they interact with the work. Once loading completes, the user is presented with a set of digitised versions of watercolour drawings cut into shapes and floating across the screen while the electronic ambient audio plays. At this stage, a visitor can affect the movement and position of the shapes and the playback of various sounds by clicking on the moving shapes. It is not immediately obvious which elements are interactive or how interaction effects them. After a period of time, the scene, or ‘landscape’, ends and a new scene loads. The same simple outlined shapes appear during the variable loading period.

In 2007, when Watercouleur Park was created, web authoring workflows and tools were in place to develop responsive and interactive sites. As the World Wide Web evolved, there was a move away from delivering static web pages towards what became known as ‘rich web applications’, which enabled interactive elements and movement. Rich web applications relied heavily on client-side technologies such as Adobe Flash Player, a browser plugin that ran within the user’s browser rather than calling on a web server for each asset or process. The Flash platform allowed the creation of complex graphics, animations and interactive experiences, which beyond the initial download time of the SWF (Shockwave Flash Movie) file, were essentially seamless. Developers were drawn to working with Flash for its ‘accessibility and ease of quick prototyping for artists, and the friendliness of its design that allows amateur creators to experiment’. The benefits of this way of authoring web media have now, for the most part, been superseded by developments in HTML and JavaScript-side technologies that allow native development of complex web applications that can run without browser plugins.

Tate’s Intermedia Art website credits David Deraedt as the programmer for Watercouleur Park and names the technologies used: Flex, Flash ActionScript 3 and PHP (PHP: Hypertext Preprocessor).21 Flash was originally developed to author and deliver animation, but features were added over time.22 Unlike Flash – the linear, timeline-centred animation software with a user interface similar to that of illustration and video editing software – Flex allowed developers to write their applications in the Actionscript 3 programming language in combination with MXML, a Flash-specific markup language.23 This code would then be compiled into a SWF file and embedded within a web page.

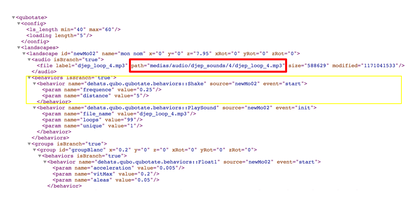

Fig.5

Contents of .xml document showing file path (outlined in red), behaviours and parameters (outlined in yellow)

When evaluating the risks for preservation of Watercouleur Park, it was useful to research how the page was built and structured. By looking at the HTML code used to structure the artwork’s page on the Intermedia Art website, we found that the SWF file for Watercouleur Park is hosted externally on the artist’s server and linked to from the Tate pages. As a test, we attempted to download the SWF file and launch it locally using the (offline) desktop version of Flash player. During this process it became apparent that the SWF file is not self-contained, and must be able to access the artist’s server to run. Unlike some of the other Flash-based works on the Intermedia Art site, such as The Art of Sleep and Le Match des Couleurs, the SWF file for Watercouleur Park does not package all the media assets that are used in the artwork internally.24 Instead, the sounds and images are stored externally in a file directory on the artist’s server. To find out more we used GNU Wget, an open-source utility designed to retrieve content from internet servers, popular in the web archiving community. Using Wget we were able to generate a list of URL addresses for all the files that sit in the same directory as the SWF file.25 We found that the SWF file remotely accesses an XML (eXtensible Markup Language) file containing some of the code, parameters and paths to files stored externally to the SWF (fig.5).26 The XML file also specifies behaviours such as the shaking of one of the pictorial elements, and the frequency and distance of that ‘shake’.

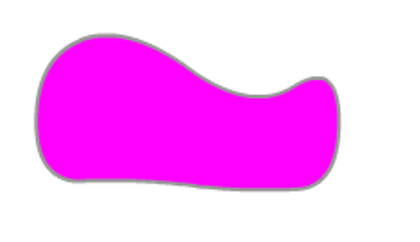

Fig.6

Example of two components of the animation that could be programmed to move individually. A PNG image (left) and SWF file (right), which could have further behaviours applied to it, such as expanding and contracting.

Fig.7

Screenshot of the SWF file used as one of the initial tests to discover what was possible in terms of animating different components of the work

The images, animations and sound assets are stored as PNG (Portable Network Graphics), GIF (Graphic Interchange Format) or SWF, and MP3 files respectively and located in labelled folders within the file structure. Examining the contents of asset folders can provide additional information about the processes of making. For instance, not all the images in the folder structure are listed in the XML document and it is likely that those are not utilised in the finished artwork. As an example, a small SWF file named ‘animtest’ (fig.7) in a folder named ‘oldtate’, an animation of a circle being deformed, was probably produced as a test.

Storing media assets externally in this way was common in Flash development as it could reduce loading times, offer more flexibility during development and enable the creation of more responsive dynamic projects, which could load media as needed. When considering the preservation of the work, this strongly affects the type of possible intervention, as the whole structure of files and folders must be maintained. We will explore this more when discussing the risks and options for preservation.

Current condition

Since 2007, changes to the way the internet works have affected the experience of web-based artworks such as Watercouleur Park. Flash was discontinued December 2020,27 which made it impossible to playback and interact with the artwork in standard web browsers. Before 2020, other changes had impacted user experiences of the artwork. During the first years of the Reshaping the Collectible project, for example, the work could be accessed on contemporary desktop computer browsers but Flash had to be enabled each time, preventing the work from loading immediately. A broader change came with the use of mobile devices to access the internet. Since 2007, when Watercouleur Park was created, mobile devices with internet access have become increasingly popular; in 2010, mobile phones accounted for less than 5% of the devices used to access the web (PCs made up the other 95%), but in 2016 their market share was already higher than PCs (50% vs 44%).28 Since most mobile devices did not support Flash, many internet users would not have been able to access the works without using another device.29

Watercouleur Park – like The Art of Sleep and The Art of Silence by Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries, also commissioned for Tate’s net art project – has an integrated autoplay function, meaning that it was intended to start seamlessly as soon as the webpage was opened.30 Many users found the unwanted video and sound irritating, as well as requiring large amounts of data in networks that may have been constrained or where data was expensive. It was an important driver to the use of ad blockers, which decreased the revenue for browser developers, who consequently moved to stricter policies on autoplay.31 The consequence of these policies for artworks is that they cannot be experienced as they were designed. In recent years the main browser developers, such as Chrome and Safari, have developed policies that allow a more controlled approach to autoplay, for instance allowing automatic playback if the sound is muted.32 Of course, this applies to newly coded pages, but not necessarily to fifteen-year-old artworks, and to re-enable autoplay the page would have to be changed.33

To preserve Watercouleur Park, or any other webpage, the website must be online to be accessible and visitors to the site must have the means to view what an artist’s server is hosting. From an institutional perspective, the first point in this case is at risk. The work has been hosted by the artists on their own servers since 2007, when the work was commissioned. It has remained accessible throughout the intervening years, but as the technologies it uses deprecate, the risk that the artists could take the work offline increases, leaving the institution with no control over its accessibility online. This is consistent with the fact that the work is a commission rather than part of the collection.

If Tate wants to ensure that the work is online for the foreseeable future, it needs to initiate a discussion with the artists to understand their views of how the work should be accessed, and what changes will be required if the work is to remain accessible online. From a preservation perspective, it would also be preferable to host the work on Tate servers. To achieve this, and given how the animation has been developed, it would be necessary not only to download the SWF files, but also to duplicate the folder structure that currently exists on the artists’ server. Thorough testing would be necessary to ensure that the work was fully functional, particularly given the risk that the URL paths could be lost.

Maintaining accessibility for this work may need a separate solution altogether. As noted, for a net art work to remain accessible online, a visitor’s device must support the technology that is used to display a work – in this case Flash. The best solution that we tested, with the collaboration of emulation expert Klaus Rechert, was to provide access via a pre-specified remote browser. This allows a visitor to view the live online artwork via a browser that supports Flash playback.34 Since Adobe announced that Flash was being deprecated, a number of projects and tools have been developed to extend the life of Flash-enabled content, by intervening either at the host level, by providing a translation layer, or at the client level with the help of a browser extension.35 Another option would be to migrate the project to a new format compatible with modern browsers. It would be worth testing the cross-compilation features in Apache Royale, the current name of the Flex framework. Apache Royale converts the ActionScript 3 code used in Flash to JavaScript, one of the core technologies of the web and therefore likely sustainable in the medium to long term.36 According to Apache, ‘as you edit and save changes to the code, the new compiler known as FalconJX is compiling not only a SWF, but also cross-compiling your source code into JavaScript, and reporting any errors it’.37 Hypothetically this approach could enable Watercouleur Park to function in modern browsers as long as JavaScript is supported.

The chosen approach would need to be agreed with the artists and the outcomes thoroughly tested to ensure that any changes introduced are understood and acceptable. It would also need to be fully documented and any changes identified to visitors to the pages.

Conclusion

Watercouleur Park feels both timeless and somewhat out of place in the history of net-based art. While it used the popular software Flash, which enabled interactive games and animations to be built into websites, the artwork produced by Qubo Gas is not as innovative in its programming as other works of a similar time period, such as those by Paper Rad, Eric Zimmerman and Geoff Lillemon.38 As such, it makes sense to consider Watercouleur Park in the context of later digital animation works, which combine hand-drawn elements with programming that builds evolving interactions and elements that react or change in response to the user’s input or an algorithmic instruction. A later work by Qubo Gas, Hullabaloo 2008–10, takes the idea of networked space in Watercouleur Park further, in that elements of the work’s landscape were anticipated to evolve. Were it still accessible, it might be interesting to see it placed alongside the work of artists such as Ian Cheng, which uses complex programming and AI-learning to ‘generate’ an endless landscape, or of Marina Zurkow, whose hand-drawn and animated works feature reflections on climate change, flooding and species diversity. Her work Mesocosm 2011, for example, changes through seasons and times of day algorithmically (where a single hour of world time elapses in each minute of screen time, so that the calendar year plays out over 146 hours).39 It is not interactive but evolves with the user’s absent-minded viewing – if you quit the browser and start it again it would begin in the winter cycle.

Tate commissioned a number of Flash-based works as part of its net art programme. As the technology becomes less accessible, artists must decide how they want their work to live on. If artists choose to present these works without their interactive elements, for example, they could be shown in the future as pre-programmed, time-based viewing experiences, presented online or in the gallery as a moving image work. (The Art of Sleep and Le Match des Couleurs can both be experienced in this way.) And, of course, the longevity of such works is dependent on access to component materials from the servers on which they are hosted and the artists’ own current interests in working online or in digital space.