The Dumpster is a net art work created by Golan Levin with Kamal Nigam and Jonathan Feinberg, co-commissioned by Tate and the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Launched to coincide with Valentine’s Day 2006, it takes the form of an interactive visualisation of data drawn from blogs in which people – mostly North American teenagers – share their feelings and experiences of heartbreak. When launched, it was possible to interact with a collection of over 20,000 breakups on a graphical interface located on a webpage.1 The interactive element no longer functions but the artwork website is still accessible via the Whitney’s Artport pages.2 It includes information about the project and its development, details about the user interface, an artist statement, an essay by Lev Manovich, selected blog posts describing break-ups, credits and detailed acknowledgements. The interactive data visualisation can be experienced through a video recording made by Levin (fig.1), in which he introduces the key concepts of the work.3

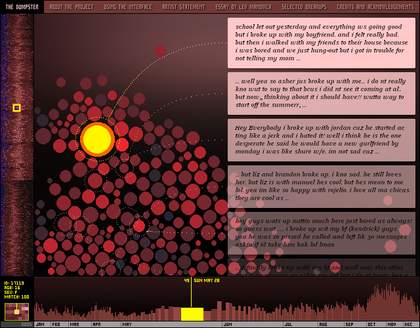

Fig.2

Screenshot of The Dumpster (installation version), showing the months of 2005 along the lower axis and nodes representing the 20,000 heartbreaks on the left axis, the selection indicated by a small yellow and red square

The visualisation takes the form of a graph. The months of 2005 are mapped along the bottom axis and on the left axis are minuscule nodes representing each of the 20,000 heartbreaks. In the centre of the visualisation are circles or ‘Breakup Bubbles’ that move continually in response to user interaction (users navigate with a mouse). Each bubble represents an experience of heartbreak. If you click on one of these bubbles, it changes from red to yellow against the setting of a deep red background. To the right of a selected bubble, a panel of text appears narrating an experience of someone being dumped: ‘Jay dumped me… for Carly…. I was enjoying scooby doo... and he called and said we needa talk... I was enjoying scooby too much so I didn’t think much of it…. then BOOM… he says its cuz he realize he’s…’.4 As a user reads about an experience of heartbreak, the program responds: bubbles featuring similar experiences cluster together. Parallels are also shown through colour coding, as the bubbles turn from a deep to a brighter red across the chart. As well as selecting the moving circles, it is also possible to select heartbreaks by month by clicking on the individual blog entries charted on the left axis (fig.2).

Making and commissioning

The data used in the visualisation was compiled in 2005 using a search engine for blogs called BlogPulse.5 Levin used a query on the database to find references to breakups (such as ‘broke up’ or ‘dumped me’) and then removed any irrelevant posts. The data was then further analysed for references to romance and, from this, the ‘highest classification scores’ were selected for the visualisation.6 The ability to explore and find patterns of experiences in break-ups was created using a language analysis program and by comparing similar characteristics. For example, the software analyses who instigated the breakup, what emotion the individual was expressing, and the gender and age of the blogger. In this way, as Golan Levin has explained, ‘visitors to The Dumpster can experience both the unique stories of specific individuals as well as observe a group portrait of a blogging generation’.7

The Dumpster was one of three works commissioned in 2006 for Tate’s website in collaboration with the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.8 The Whitney presented these works on Artport, a section of its website that is set up to document and provide access to online artworks from Whitney exhibitions and collections. The commission was instigated by curator Christiane Paul, the initiator of Artport and a friend of Levin’s. A few years earlier, Paul had commissioned Levin to create Axis 2003 and included Levin’s The Secret Lives of Numbers 2002 in the Whitney Biennial the following year.9 Levin shared his ideas for The Dumpster as it was developing, and Paul proposed that this could be realised through a commission for the Artport and subsequently Tate.

The idea for the work came about through a conversation between Levin and computer scientist Kamal Nigam, who was working for a machine-learning company employed to investigate potential terrorists in the wake of the 9/11 terrorist attacks in New York by searching through global blogs. Nigam found that, instead of potential terrorist plots, blogs were filled with teenagers discussing their romantic lives. Fascinated by this seemingly unintentional subversion of attempts by the state to monitor and control information circulation, Nigam searched the data and provided Levin with a file. Levin then brought in software engineer Jonathan Feinberg to create the backend of the work. Feinberg has collaborated with Levin on a number of works and with other net artists including Martin Wattenberg and Marek Walczak on another Tate commission, Noplace.10 For The Dumpster, danah boyd, a specialist in how young people use social media, was invited to advise on protecting the privacy of the bloggers whose writing appears in the work.

Reception and interpretation

The Dumpster can be understood as a series of self-portraits and a collective representation of the common experience of heartbreak. In a statement about the work, Levin wrote that he is ‘drawn to the revelatory potential of information visualization – whether brought to bear on a single participant, the information culture we inhabit, or the formal aspects of mediated communication itself’.11 The statement further described how when ‘used as an interrogative mode of artistic practice, information visualization has the potential to offer us a new perspective on ourselves’.12 The work can also be seen as a witness to shifts in global communication towards personalisation and social interactions.

In 2004, the term ‘Web 2.0’ began to be used to describe new website designs that allowed users to interact and collaborate with each other through social media and user-generated content.13 The creation and popularity of blogs was an important part of this development. Before the arrival of Facebook (2004), Twitter (2006) and Instagram (2010), blogs were the most common way for people to self-publish their ideas, emotions and experiences. By drawing on data shared by individuals through their blogs, The Dumpster captured a moment of transition in the self- and social portraiture of online communications. By aggregating and visualising personal, supposedly trivial, teenage experiences, Levin subverts the co-option of internet search applications used by nation states and governments to surveil potential security threats.

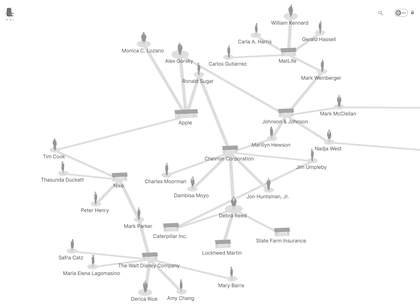

Fig.3

Screenshot of Josh On’s They Rule 2005–ongoing, which maps the social networks of board members of large corporations

Accessible at https://www.theyrule.net/

The new ways in which societies communicate online was the focus of a particular subset of net art. As Levin has described, ‘the kind of net art that I was doing in the early 2000s, in this particular case, had to do with the idea of doing data visualisations as a mode of artistic practice’.14 Other artists working in the same area as Levin include Martin Wattenberg, whose Spiral 1999 created a visualisation of the Rhizome.org database of texts,15 and Josh On, who created They Rule 2005–ongoing (fig.3), which exposes the social networks of the members of boards of large corporations.16 Levin also makes the comparison between net art involving data visualisation and Cory Arcangel’s Working On My Novel 2014. To create this work, Arcangel found people on Twitter who posted the words ‘working on my novel’ and selectively published their tweets in a book.17 Working On My Novel charts how a creative endeavour becomes a collective experience through social media. Like The Dumpster, it makes visible personal experiences and the potential this creates for community.

In an essay commissioned by Tate and the Whitney to coincide with the launch of the work, writer on digital culture and new media Lev Manovich connects the ordering of subjective and social experience in The Dumpster to a longstanding tradition of portraiture in the arts.18 He describes the artwork as a ‘social data browser’ in which ‘the particular and the general are presented simultaneously, without one being sacrificed to the other’.19 In a review of the work published in Art Critical online magazine, Amber Ladd places The Dumpster within the context of the shift within internet search engines towards personalised or ‘social’ search.20 The new search applications, launched by Google and Yahoo! in 2005 and widely used since – including in The Dumpster – enabled search engines to address ‘opinion-queries’ (sourcing responses to queries from friends and authorities) and to interpret and personalise a ‘user-query’ (finding items that would be relevant to a user’s other searches).21

The Dumpster has also been interpreted in relation to aesthetics and digital practices. For media theorist Timothy Scott Barker, with its process of both archiving and assembling, ‘the information [in The Dumpster] is visualised in such a way that [it] produces a group portrait of participatory culture and composes a multitemporal history of relationship beginnings and endings’.22 For artist David Jhave Johnston, it can be understood as a form of collective poetry:

The Dumpster exemplifies the uncategorizable object that lurks at the edge of poetic discourse: simultaneously infographic and crowdsourced, it is an immense reservoir of phrases orbiting love, and as such constitutes a dynamic sprawling networked poem whose form echoes geology.23

The artist’s practice

Golan Levin is an artist, researcher, engineer and educator. He is interested in exploring ‘new modes of reactive expression’, whether through interactivity, cybernetic systems, performances, digital artefacts or virtual environments.

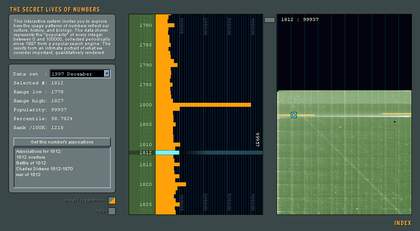

Fig.4

Screenshot of The Secret Lives of Numbers 2002, a collaboration by Golan Levin, Jonathan Feinberg, Shelly Wynecoop, Martin Wattenberg, David Elashoff and David Becker

Levin studied undergraduate and postgraduate degrees at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Media Laboratory. Between degrees (1994–8) he was involved in the internet research think tank Interval Research Corporation in Silicon Valley, California.24 While at Interval Research and at the MIT Media Laboratory, where he worked after graduating, Levin began to create interactive, computer-animated works, including Yellowtail 1998, a real-time animation that responds to lines and movement coming from a cursor on the screen. In 2001, he collaborated on Dialtones (A Telesymphony) 2001, a performance in which sounds were created using the ringtones of the audience’s phones.25 The Secret Lives of Numbers 2002 represents a move within his practice towards data visualisation (fig.4). The work is an interactive visualisation of a study into ‘the relative popularity of every integer (a number which is not a fraction) between zero and one million’.26 In 2009, Levin’s Opto-Isolator 2007, an artwork that looks back and responds to the gaze of the viewer, was included in the exhibition Decode: Digital Design Sensations at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London.27

Technical narrative

The Dumpster comprises a website containing multiple pages, mostly static and contextual, while the interactive component of the artwork is a Java applet embedded in the homepage, which would load automatically when a visitor came to the page. Java applets are small applications written in the Java programming language. They are delivered to users in the form of Java bytecode and executed within a Java virtual machine (JVM) in a process separate from the web browser.28 In order to run the artwork on a computer it was necessary to have a browser that supported applets, as well as a JVM installed on your computer. If the latter was not present, the visitor would be presented with a link to download one. The applet itself was authored using Processing, a free, open-source programming framework aimed at visual artists, designers and architects.29 Processing was initially created in 2001 by artist Casey Reas and designer Ben Fry and has since become a key programming framework for art and design.

Kamal Nigam, who at the time worked for Intelliseek’s Applied Research Center,30 had access to a scraping of all the blogs on the internet for 2005. Together with Levin, Nigam used BlogPulse, a search engine optimised for blogs, to search for terms such as ‘broke up’ and ‘dumped me’. The resulting posts (numbering several hundred thousand) were then scored by a machine learning classifier trained to recognise posts about romantic breakups, in an effort to eliminate false matches, for example, posts about bands breaking up.31 This was done using TF-IDF, a technique commonly used in search engines, information retrieval and text mining that weighs the importance of specific words or expressions in a corpus of texts.32 At the end of this process, the 20,000 most highly scored posts were included in the visualisation. Andrea Boykowycz developed a database tool for cleaning the data and Jessica Greenfield, Joel Kraut and Giana Gambino are mentioned on the website as having helped to ‘prune the data’.33 These posts were then stored on a database in the backend of the website developed by Jonathan Feinberg, from which the Java Applet draws its results.34 The applet provided the graphic interface to visualise the dataset. It used parameters such as the age and gender of the blogger, whether someone was cheating or who broke up with whom, to identify and group similar types of breakup, which could be browsed by the visitor.

The work is hosted on the servers of the Whitney Museum of American Art, with whom Levin collaborated more closely than with Tate.35 On the Whitney site the work is displayed in the context of the museum’s Artport pages. Its URL begins as https://artport.whitney.org/commissions/thedumpster/, with each page having its own specific URL.36 When the work was visited from the Tate site, it appeared under http://www2.tate.org.uk/netart/bvs/thedumpster.htm. This page contains an embedded link to the Whitney pages in its code, so when visiting the artwork pages from the Tate site, the whole site appears to sit under one URL only, and on a Tate server.

Beyond the online version of the work, Levin also created a ‘kiosk version’, meaning a self-contained software that can run offline. This version was initially created in 2006 to show the work in gallery settings. It was updated in 2013 to include applications for MacOS, as well as Windows 32 and Windows 64 bit. The resolution of the online version was kept low, at 640 x 480 pixels, to accommodate the variable hardware of online visitors, but with the gallery version it was possible to stipulate the hardware, and the work was displayed at a higher resolution of 1024 by 748 pixels.

Current condition

The work has not been playable in a regular browser since 2016, when the type of Java applet upon which the data visualisation element of the work depends was dropped by Oracle, a key developer of the Java framework.37 We therefore first experienced the work by the means of videos created by Levin, which are available online.38 The website containing the data visualisation software is still on the Whitney website and it contains thorough documentation of the work, the context of creation and an artist statement.

An artist’s engagement with the documentation and preservation of their own work is particularly important for net art, and Golan Levin’s website demonstrates his continued commitment in this regard. Not only does he document the functionality and production of the artworks, but also often describes any interventions or updates. For instance, the history and software for the different versions of The Dumpster can be found on Levin’s page on GitHub, an online software repository often used by open-source projects.39 The page about the artwork on Golan’s website has been moved to the ‘archive’ section and is still live and findable.40 From the GitHub page, it is clear that a new version was created in Processing in 2013, with further developments in 2020. This version has not yet been placed online.

After reading the available documentation, and with some further exploration, we found an extension to the Google Chrome browser – CheerpJ Applet Runner, developed by Leaning Technologies – that will playback the applet.41 Using this tool is not a preservation solution as it depends on the original software remaining available online, but adding it to a browser will allow the playback of the applet. This meant we were able to view and experience the site and its interaction, and we could create additional structured documentation. This type of tool can be useful to researchers, although we would not expect occasional visitors to install it for a one-off viewing.

The other important aspect to consider in the preservation of this work is the database containing the blog excerpts. For the applet to display sentences it must be connected to the database; when that fails, no text will appear in the balloons; only the word ‘Connecting’. Any preservation measure must take this into consideration and would require the maintenance of the servers currently hosting the work online. Fortunately, the Whitney Museum of American Art – and curator Christiane Paul in particular – have demonstrated a longstanding commitment to preserve and maintain these works in Artport.42

In our initial interview with Levin, he described some of the possibilities and limitations of the software he uses for the future of The Dumpster. He discussed the possibility of porting the Java applet to JavaScript, using P5.js, a client-side library used to create graphic and interactive experiences, and part of the Processing ‘family’ of programmes. This intervention he said ‘would give [The Dumpster] life for another number of years, until the day that they decide that JavaScript was no longer going to work in the browser’.43 Levin’s comment is based on the reasonable expectation that JavaScript will remain sustainable for the foreseeable future. According to a review of job adverts by IT Jobs Watch, which is a good indicator of levels of adoption and hence long-term sustainability of programming languages, it is one of the most in-demand programming languages.44

It is important to consider the longevity of the programming language when migrating software. Choosing a widely used language means that the artwork is likely to remain functional for a reasonable period of time and that if further updates are needed there is a wide pool of experts to draw from, even in the absence of the artist. Following the discussions around this work, the artist upgraded the software and made the updated version and the source code for the work available on his GitHub page.45

For this type of preservation intervention, where significant decisions have to be made about how software is migrated (and hence changed), it is best to work with the artist whenever possible. They, or their teams, usually have the most in-depth knowledge of the software systems and can approve any changes that may be needed, on a technical, functional and aesthetic level. In the interview, Levin made the point – echoed in conversations about preservation we had with other artists – that he could spend all his time just keeping his early works running: ‘It doesn’t get done for free, is the problem. I’m not saying this because I want money. It’s more just like, you know… I’m 47 now. I could spend the rest of my life maintaining my old shit. That could just be my career, just like keeping the shit from my 20s running.’46 Key to preserving works over time is finding a balance between the time an artist can or wants to spend upgrading or restoring their work and an institution’s or collector’s role in maintaining the works in their collection.

Conclusion

In 2006 blogging was an increasingly widespread activity and the move to pen shorter ‘status updates’ as introduced by Web 2.0 platforms, such as Facebook, had not yet become embedded in our online habits. The pain of a break-up (or the joy of a new love) would soon be noted not with a personal story but with an automated post notifying friends or other users that ‘Sarah has updated her relationship status to married’. As a result, The Dumpster occupies a significant place in the history of how the web was used as a personal space in the early and mid-2000s and charts the associated personal privacy risks. It sits in relation to other user-content driven net art works such as Olia Lialina and Dragan Espenschied’s One Terabyte of Kilobyte Age 2010–ongoing, which uses an archive of lost personal GeoCities webpages to create different web-based and offline installations, or Paolo Cirico and Alessandro Ludovico’s work Face to Facebook 2011, which scraped hundreds of thousands of Facebook profile pictures, names and details and used a facial recognition algorithm to group them and populate a fake dating site.47

Artists have long appropriated other people’s information to create new work but The Dumpster’s simple interaction and playful interface is an exceptional early example of data visualisation. With the release of Processing – the software language first created by artists used in many works of data visualisation – navigating data by clicking on bubbles or spheres, which each represented different ideas or content, became a common experience of being online. This aesthetically simplifies, and perhaps obscures, the complex coding behind the interface. The Dumpster and other projects that sought to expose or reflect on the machinic tracking of message content, such as Warren Sack’s Agonistics: A Language Game 2004 (also shown on Artport) or Annina Rüst’s Sinister Social Network 2006 (developed while she was studying at MIT), are important weigh-stations on the inexorable road towards today’s fully ‘artificially intelligent’ semantic analysis and corporate surveillance of what we say when we are online.48 In the context of ongoing debates about whether spending time online reduces or increases social isolation, it is always nice to be reminded that even if your heart is breaking, you are not alone.