Screening Circle 2006 is a collaborative online artwork created by Andy Deck through which users can create colourful designs by viewing and editing designs made by others. The work can be accessed on Andy Deck’s website, which is linked to from the Tate Intermedia Art webpages and via artport, the Whitney Museum of American Art’s online portal for net art. As this text was being completed in September 2023, Andy Deck had been updating the artwork, so that functionality lost by Flash’s end of life was mostly restored.

Fig.1

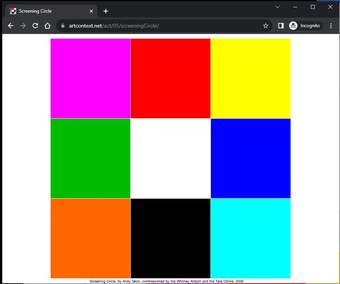

Screenshot of the start screen for Screening Circle 2006 by Andy Deck

Fig.2

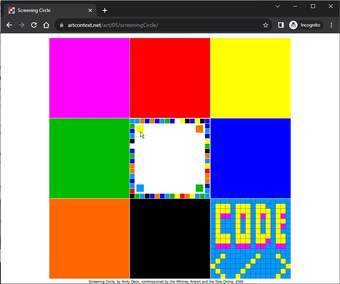

Screenshot of the Screening Circle start screen after clicking on the lower-right square to reveal the menu item ‘CODE’

The start screen consists of a three-by-three grid of nine coloured squares (fig.1). Initially, when the user moves their cursor over the outer squares, they show an animation of coloured lines moving towards the central square; when an outer square is clicked on, however, different options are revealed in pixelated lettering (fig.2): ‘PLAY LOOP’, ‘HELP DOCS’, ‘Art-port Tate’, ‘VIEW’, ‘andy deck’, ‘CODE’, ‘INFO’ and a character that resembles a small ‘a’, a kind of artist’s logo that stands for Andy, art and @. This ‘activated’ version of the page also serves as the menu page.

Fig.3

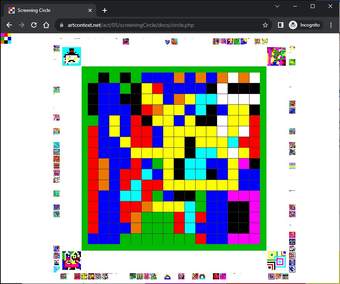

The drawing page of Andy Deck’s Screening Circle 2006 where users can edit a design by changing the colour of individual pixels

Clicking on the central white square takes visitors to the drawing area. There, a continually changing border of brightly coloured designs pulses around an empty white square at the centre. Selecting any of these moving squares brings it, along with three others, into the internal space; clicking on one of these three squares brings it into the centre of the group and allows the user to edit a design by changing the colour of individual pixels within it (fig.3). Each pixel can be changed to one of nine available colours. Clicking on any other design on the outer border will save the one the user has been working on. The ‘PLAY LOOP’ function on the launch menu plays through these designs in a rapid sequence, while ‘VIEW’ allows the user to see visual representations of any edits archived to a particular date.

Users can return to the menu page for Screening Circle by clicking the small grid at the top left of the browser window. There, each section of the surrounding grid provides a route to further information about the work. In the ‘INFO’ section, for example, Deck reveals how part of the inspiration came from ‘the tradition of the quilting circle’ where ‘a group of people [would] make a quilt together, each producing small squares that are later sewn together’, explaining that in Screening Circle this has been ‘reinterpreted for the context of interactive electronic media’.1 In the same section, Deck explains how the design constraints in the work, such as limiting the number of colours users can select from, were intended to encourage participation and creativity, since ‘the emphasis shifts to the many things that are variable’.2 Within even this fairly limited framework, users could choose to create abstract images, write words or draw recognisable shapes or forms.

The ‘INFO’ section also considers access and copyright issues, noting that Screening Circle ‘should be considered part of the creative commons’.3 This reflects Deck’s commitment to open source technology. In the ‘CODE’ section of the site, Deck describes how the JavaScript source code for Screening Circle can be ‘peeked at’ using the ‘Source View’ function in the browser, and offers to provide users with further PHP and C language code upon request.4 In this spirit of openness, Deck also makes his contract with the Whitney and Tate available to ‘peruse’ on the ‘Artport-Tate’ section of the site.5

Making and commissioning

Screening Circle was one of three works co-commissioned in 2006 by Tate, for its Intermedia Art pages, and the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, for artport, a website set up to provide access to online artworks as well as documentation of net art and new media art from Whitney exhibitions and collections.6 Having previously collaborated on Gate Pages 2001, the first net art work on artport, Deck was approached by the Whitney curator Christiane Paul to create a work for artport and Tate.

Fig.4

Installation view of Andy Deck’s Screening Circle 2006 at Miniartextil, International Exhibition of Contemporary Textile Art in Como, 2006

In addition to being accessible online, Screening Circle has also been exhibited in 2006 as an interactive installation at Miniartextil, International Exhibition of Contemporary Textile Art in Como, Italy, curated by Luciano Caramel with New Media Art curator Domenico Quaranta (fig.4).7

Reception and interpretation

Screening Circle builds on Deck’s earlier work Glyphiti 2001, a program inspired by MacPaint software in which people can create and edit images by selecting whether pixels in a choice of designs should be black or white.8 Like Screening Circle, Glyphiti attempts to shift notions of authorship from private into public space. Deck set the parameters for the works, programming the size of the grid and limiting the available colours to black and white. The images were individually created through user participation and form part of an ongoing archive.

The limitations Deck put in place for Screening Circle can also be understood as a consideration of the work’s context, as a commission for large-scale institutions serving a range of audiences. Deck has reflected on concerns about people writing and drawing obscene or offensive things on Screening Circle, which was an outcome he experienced with Glyphiti. In the design, he tried to create a space in which ‘there was an element of freedom of expression but that it would be hard to write out whole sentences about how people felt about the institution or things like that’.9 Deck was also interested in creating net art that invited people to collaborate and make creative decisions: ‘I’ve always wanted to put the responsibility for some of the design decisions or some of the artistic decisions on the user. When it’s a collaborative piece like that, I want other people to choose things’.10

When it was launched in 2006, Screening Circle was contextualised on the Tate and Whitney websites through a description of the work and an essay commissioned by new media art specialist Alison Coleman. The essay draws on Deck’s reference to quilting circles, considering both as forms of public art that deal with ‘community members and prioritise social issues and political activism’.11 Screening Circle, Coleman continues, carves out a space for ‘shared authorship’ as each participant ‘interprets the work… through their own contributions’.12 These ideas of shared authorship are celebrated by artist, designer and researcher Yueh Hsiu Giffen Cheng in their essay ‘The Aesthetics of Collaborative Creation on the Internet’. Cheng describes how Deck’s work invites users to experience and create the artwork simultaneously, becoming ‘editors’ and ‘artists’ as well as viewers.13

The curator Domenico Quaranta, who co-curated the installation version of Screening Circle in Como in 2006, also highlighted the participatory nature of the work. For Quaranta, the design of the program encouraged the participation of those ‘not truly sure of their creative gift’ by putting people at ‘ease with an elementary interface’ that ‘makes the process truly open’.14 Deck has expanded on his decision to create something ‘generic rather than too personal’, as a way of inviting a sense of collective ownership into each design.15

The artist’s practice

Fig.5

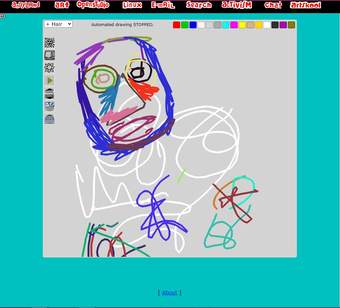

Screenshot of an ‘automated drawing’ created on DraWarD 1995–96 by Andy Deck

Andy Deck creates public art for the internet that invites collaboration, and creative and collective play. This is often combined with a desire to create space for people to think critically about the power, control and commodification that lies within software and online environments. In an interview given in 2010, he underlines the relationship between online space, capital and accessibility: ‘I hate to see everything we play with online become a commodity. It excludes the billions of people who can barely afford electricity and connectivity’.16 In 1990 Deck began making computer paint programs that could be used to create time-lapse animation. From there, he began to work with the internet and JavaScript, using the programming language to extend his programs into collaborative online environments. One example of this is the work DraWarD 1995–96, a whiteboard with which people could draw and interact online (fig.5).17

Many of Deck’s works are driven by data.18 CultureMap 2000 uses data collected from search engines to produce an interactive visualisation of the prevalence of various words on the internet. As well as picturing the evolving content of the web over time, the work highlights the commodified nature of online environments.19 Other works present the effects of warfare, conflict and the nation state. Antiwar 404 2009, made in collaboration with getpeaceful.org, a non-profit media initiative and website cofounded by Deck that ‘uses online media to highlight peace advocacy across the globe’, is a database documenting lost or disappeared anti-war websites. Like many of his works, Antiwar 404 was designed to be shaped in collaboration. On the work’s website it states: ‘Contributions to this collection from the general public are welcomed’, although it is unclear if this is still possible.20

Over time, Deck varied the level and types of control available to the user in each work to balance the individual agency of each user against other users and the structure and goals of the work. The artist has explained that, in comparison with 2006, ‘people are less patient in experimenting with interfaces... They have expectations that are baked into their way of interacting with screens that just didn’t exist at that time’.21 This was evidenced at the ‘Lives of Net Art’ event in 2019, programmed as part of ‘Reshaping the Collectible: When Artworks Live in the Museum’, for which the artwork was set up at Tate Exchange in Tate Modern, London.22 The researchers present at the event observed that many visitors did not understand how to use the interface, and required an explanation by members of the team.23

Deck often collaborates with other net artists. For example, he worked with net artist Mark Napier on GraphicJam 1999, a collaborative drawing hosted by THE THING, the online community for media art, activism and cultural criticism, founded by Wolfgang Staehle.24 He has also created works with Andrej Tisma and co-founded Transnational Temps, an environmental arts collective, with artists Veronica Perales Blanco and Fred Adam.25

Technical narrative

Unlike many of the other works commissioned for Tate’s net art and intermedia art sites, Screening Circle was functional for the duration of the ‘Reshaping the Collectible’ research project. This allowed the team to gather a technical narrative by interacting with the work itself. In addition, the ‘CODE’ page contains a wealth of information, and researchers held several conversations with the artist about the website’s technical make-up.

The technical infrastructure of the work is split between the browser and server side. On the browser side it relies on JavaScript to navigate through pages, to display the interface for drawing images and to call and display past images from the server side. It uses the Asynchronous JavaScript (Ajax) and XML approach, which means the website sends requests for data to the software on the server side – in PHP (Hypertext Preprocessor) and C code, including GD Graphics Library and libflv – to create and animate GIFs that are then displayed by the browser.26 Deck also uses Flash Video (.flv files) and GIFs in the work.

Many of the works featured on Tate’s Intermedia Art website make use of rich internet applications (RIAs), such as Flash (Le Match des Couleurs 2000 by Simon Patterson) and Java Applets (The Dumpster 2006 by Golan Levin).27 These applications require the download of an application as well as a plugin installed in the user’s browser. By using Ajax, Deck partially avoided the reliance on plugins. The choice also enabled immediate interaction, even at low internet speeds, since with Ajax it is possible to load new elements to the page without reloading the entire page in response to a user’s input. In this way, the interaction is nearly immediate, in spite of the much lower data rates of internet connections at the time.28

Deck has highlighted the technological difficulties in making the work during a time when many of the standards and workflows relied upon in this type of production were newly established or not widely supported:

It’s worth pointing out that the source code for Screening Circle is not especially pretty. Using JavaScript (ECMAScript) to make this piece has been a little like eating soup with a fork. It’s pretty discouraging that the most elegant language for making experimental, interactive, online media – Java – is struggling to survive as an online content format in the face of Microsoft’s belligerence.29

Because Screening Circle is built using asynchronous JavaScript, it is made up of many discrete elements that Deck was able to manipulate directly at a lower level than is often possible with the higher-level authoring environments aimed at playback via a plugin. This informed the structural and aesthetic choices that Deck made in the production of the work and his long-term maintenance of its functions. For example, Screening Circle records all users’ input to the drawing area in a database. These interactions can then be searched by date and rendered as animated image sequences in either .flv format, which requires the Flash plugin to play back, or as GIFs, which play back natively in the browser like all other elements of the work. In order to minimise the amount of server space required to store the user-generated interaction data, Deck implemented his own encoding system. The communication between the interface in the browser and the PHP scripts on the server are also optimised for efficiency using an artist specified format.30

Under the ‘VIEW’ section of the website, the .flv playback option makes use of a server-side Flash video encoder that Deck selected because it does not use anti-aliasing to soften or fill in the jagged edges of lower resolution images. This maintains the crisp pixel structure of the graphics, making them consistent with the aesthetic of the rest of the work. Deck recounts how direct engagement with new technologies – such as the server-side encoder library that could render out the .flv animations from users’ interactions – encouraged him to develop this element of Screening Circle even though it is not part of the central interactive area of the work.31

The developers whose projects made Screening Circle possible include Thomas Boutell, who created GD Library, Stanislav Malyshev, who created a patch for GD Library that allowed the creation of the animation, and Klaus Rechert for his work on the libflv library.32 Deck not only uses these libraries but also contributes changes to them, demonstrating his engagement with open source code and tools. As a consequence, rather than use the common tools of the period, such as Flash or Java Applets, Deck chooses to use variants of JavaScript. These, he explains, are ‘broadly supported in Internet browsers and my use of the language can be interpreted as both a rejection of corporate-driven media infrastructure, and as an endorsement of the standards bodies that are working to achieve consensus about technology protocols and software languages’.33

Current condition

Deck’s works are ‘systematic in nature’; they are live and growing systems rather than objects and as such require a particular kind of ongoing maintenance: ‘I have a lot of old code to tend in my garden… I am actively updating my work to make it stay operational insofar as I can.’34 Deck has made the decision to keep the majority of his works on his own server, with some of the source code available to download,35 also providing metadata to archives that include his work. This means that others can have access to the data and or can link to his works while the responsibility for its stewardship and preservation remains with Deck. This decision, which can be understood as his ‘attachment to autonomy’,36 means the artist retains control over how his works are accessed (for free and without adverts), and that he remains in control of ‘how to adapt or “retire” my work when technologies change’.37

In a 2021 article on the conservation risks of ephemeral platforms, Deck reflects on the scale of this work:

Since the mid-1990s I have built and maintained a succession of six different servers to host my online work. Because it is not practical to maintain old operating systems when setting up new computers, application software must be compatible with new operating systems. For me this has meant that each new server installation had a higher version of the PHP language. Thousands of lines of code needed to be brought into conformity with new versions of PHP.38

In his correspondence with Tate for Reshaping the Collectible, Deck identified all the key issues in preserving his work, as well as several solutions. For instance, he has recently discovered a way to play .flv files using JavaScript.39 Other upgrades or amendments Deck has made include replacing Flash-based elements in his work with P5.jS and other HTML, CSS and JavaScript solutions.40 He has also cited the use of Web Sockets and jQuery in his restorations of older works.41 Deck wants to be able to account for changing platforms in the ways people encounter his work, for example by creating tablet-friendly versions, but acknowledges that works are also historic. For instance, he has reflected that it has become difficult to sustain the pixelated, ‘hard-edged’ look with the current softened-edge designs of software programs.

For Deck, Screening Circle belongs to its time and its context is crucial to understanding the work.42 This is not just art historical context but also knowledge of how the internet was experienced at different moments in time. With this information, and continued engagement from both artist and institutions, there is potential for the work to be updated for current platforms, such as tablet and smartphone, and ensure the work remains ‘active’ for years to come.43

Conclusion

With its seemingly simple interface and invitation to draw and connect, Deck’s work prefigures the collaborative behaviours of users evident on more recent online platforms (such as the use of TikTok to layer musical performances into new compositions) and other participatory artworks made for the web. One well known example is Ai WeiWei and Olafur Eliasson’s Moon 2013, which invited users to leave their mark in an ever-expanding wall of graffiti.44 Yet Moon differs from Screening Circle, which came before it, and TikTok, which came after it, in both scale and intention: users do not get to know each other, and no single user knows how it functions. Collaborative drawing applications on the net using Web 2.0 interfaces change how Screening Circle might be remembered in the future, by users and non-users alike. It may be more useful, therefore, to consider it in relation to earlier community-oriented systems for online co-production, such as Nine(9) 2003 by Mongrel.45 This online ‘knowledge map’ sought to link artistic gestures, such as photographs, texts and links, together in a simple user interface so that ‘the networked maps become a communal knowledge map’.46

‘Do It With Others’ (DIWO), has been an important tenet in British media art, and a year after the launch of Screening Circle the art and technology gallery Furtherfield launched their DIWO mail art project, in which they used the NetBehaviour email list for people to exchange works, culminating in an exhibition at HTTP Gallery in London.47 Furtherfield wrote of that exhibition:

Participants worked ‘across time zones and geographic and cultural distances with digital images, audio, text, code and software. They created streams of art-data, art-surveillance, instructions and proposals in relay, producing multiple threads and mash-ups’. Co-curated using VOIP and webcams, the exhibition at HTTP Gallery displayed every contribution [as] an email inbox, alongside an installation of prints of every image, and a running copy of every video and audio file submitted.48

At the same time as this, Furtherfield was hosting workshops with young people within Visitors Studio, their ‘artware for live collaborative audiovisual remix’, which referenced AndyLand as an inspiration for its creation. This was an online environment that enabled all kinds of artistic production and chat in real time, in a ‘many to many dialogue and networked performance and play’.49 Visitors Studio is no longer online, but the spirit it instilled, in using the web as a space to extend creativity, and most importantly to do it with others, and teach others how to do it, remains.