Nonrepetitive 2011 is an online, interactive, real-time sound work by Achim Wollscheid that was hosted on Tate’s website between 2011 and 2012. When it was launched, Nonrepetitive could be accessed via the Intermedia Art pages of the Tate website, under its ‘Archive’ section, with a page introducing the work and a link that opens Nonrepetitive in a new window. On accessing the work, users would encounter a window with a thin black line on a white background (fig.1), and a constantly changing sound would begin playing. Users would be able to move the line by clicking and dragging it, and to see other people moving the line. The movement of the line would be reflected in changes to the sound.

The sound produced is reminiscent of sonar, amp reverb and early dial-up internet, with a regular and then irregular pattern of gentle or loud beats, knocks and at other times ‘a screeching noise’.1 They were created by Wollscheid recording scratching and tapping on his computer keyboard, and then manipulating these sounds using the software Pure Data. The sounds that played in Nonrepetitive were built to be ‘random, supplied by some kind of chance operator within the program’, but also responded to the active movements of the user’s cursor.2

Nonrepetitive was collaboratively produced and experienced collectively. Each visitor to the webpage could see modifications enacted by other online users, creating a continuously variable experience over time. Wollscheid describes the interactive element of the work as follows:

Grab the line – which depicts the sound spectrum of what is currently being heard – and start drawing. Everyone else online on the site will see (and hear) the change. In other words: the piece is not a downloadable app, but a piece of music that is online in real time and can be seen, heard and changed by everyone at the same time. The piece is, so to speak, an object that is played and traded with.3

The sound produced was a random variation, created within the computer program, which evolves as people use it.4 Wollscheid explains the idea behind this approach as ‘to use the composition as an interface to connect people who then would play with the sound and each other. Kind of a very complicated ping-pong’.5 The name Nonrepetitive is taken from a computer music problem that circulated during the 1960s concerned with how to programme a piece of music that would not repeat.6 As a proposed answer to this problem, Nonrepetitive brings people together to collaboratively create a non-repeating, never-ending work. The program would never allow ‘constant silence’ and if it crashed it would be automatically restarted.7 In explaining his interest in unlimited duration, Wollscheid refers to the time-bound properties of different media: ‘The medium decides what can be done: 3 minutes of music on a single, 27 minutes on the LP, 80 minutes on the CD and never-ending on the computer’.8

Making and commissioning

The seeds of Nonrepetitive began in 1992 on Radio X, a Frankfurt-based radio station founded by Wollscheid and other artists.9 German law requires radio stations to transmit at all times – the airwaves can never be silent. In response, co-founder Petra Ilyes suggested creating a never-ending sound piece to fill empty timeslots and Wollscheid designed a basic model for a sound that would ‘evolve from certain parameters’ but within a closed system.10 Although Radio X did not ultimately broadcast the programme, Wollscheid was interested in how his work could become a ‘playground that would give others the chance to manipulate and communicate’.11 He developed these ideas in part through the Tate commission.

Along with five other composers, Wollscheid was invited to take part in The Sound of Heaven and Earth at Tate Modern, London, in January 2005.12 Seth Kim-Cohen, the organiser of the event, invited each of the composers to produce a new work that could be played on the night by an ensemble of musicians. The works could only be communicated to the musicians through a ‘sound score’ that could take forms other than the written word. Wollscheid’s contribution Replika took the sound in the room as the starting point.13 He continually recorded, processed and replayed the ambient noise, resulting in a composition that took the shape of a ‘continuing interchange’ between those in the room and the environment of the auditorium.14 In his review of the event for The Wire, Clive Bell captures the experience of hearing the work:

30 seconds of live playing is followed by 30 seconds of freshly processed sound from Wollscheid’s laptop, as he throws back a version of what has just been heard. The musicians respond to the android serenade, and on we go… once the expressionistic, gestural splattering is out of the way, the music settles to a rewarding group exploration.15

Wollscheid returned to work with Tate in 2010 at the invitation of Kelli Alred (then Kelli Dipple), who was Curator of Intermedia Art between 2007 and 2011. Alred had previously been Webcasting Curator at Tate and had worked with Wollscheid on The Sound of Heaven and Earth. She approached the artist in 2010 to propose a commission for Tate’s website. Alred and Wollscheid agreed that the work would be active for one year, partly dictated by the budget for hosting the work online. It was the last of the net art works to be commissioned by Tate.

Reception and interpretation

Sound artist, writer and theorist Brandon LaBelle has identified Wollscheid’s interest in the ‘crowd as an input’, creating a space for ‘networked production’ rather than any kind of ‘singular authored object’.16 In the way it is activated by the input of an online crowd, Nonrepetitive explores this interest in transformation through collective production. Wollscheid’s engagement with people and technology can be traced back to his collaborations with musicians Ralf Wehowsky and Stefan Schmidt, and with the artist Charly Steiger, in the 1980s.17 Together they experimented with cassettes and vinyl, sending them across Europe, North America and Australia; whoever received them was invited to further manipulate, destroy or add recordings to them and send them back. LaBelle describes this process as ‘sound practice in the form of social network’, in which ‘the postal system became a kind of relay mechanism aiding the transportation of sound and the coalescing of an artistic network’.18

The writer and composer Bernd Leukert discusses the work in terms of Wollscheid’s influences, from rock music to the experimental avant-garde, and highlights the importance of the social in his work.19 For Wollscheid, the internet provided the potential for play, technological interaction and transformation. As a method of distribution, it also enabled access to a broad, global audience.

The artist’s practice

Wollscheid makes radio works, sound works, performances and installations that play on the interactions between light, sound and architecture. His recordings can be found under the name SBOTHI (Swimming Behaviour of the Human Infant) and the German electronic noise music collective P16.D4. Wollscheid often works collaboratively: he co-founded Selection in the 1980s, an organisation that produced and distributed records, CDs (under the name Selektion) and art projects; he also co-founded Tutorial postmodern, Radio X (a non-commercial radio station in Frankfurt) and a2w2.net, a collaboration with architect Anke Wünschmann exploring relationships between architecture and the social, media and infrastructure, organisations and individuals.20

Wollscheid considers ideas of transformation through the production of interactive and collaborative experiences:

My approach is to develop whatever artwork I do as some kind of interface. It’s not something that you should just look at or listen to. It’s something that you can transform. There is no onlooker. They are actors, and they can cooperate or co-act with the functions that I present.21

In Translations, a performance with Kenneth Goldsmith in 2008, Wollscheid manipulated the audience’s mobile phone signals while Goldsmith read his conceptual poems.22 In another performance, Activating the Medium, organised by the sound organisation 23five at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in 2001, Wollscheid made three circuits of the auditorium. On the first, he created noises by ‘tapping and scraping various surfaces with a cigarette lighter and a can’; on the second he ‘augmented the sounds with a complex trill of amplified chimes which his laptop generated in response to any sounds coming from the room’; and finally, he ‘changed the settings on his computer, which now emitted fragmented slabs of noise in response [to] any sound generated in the space’.23 Between each change in sound he addressed the audience with this question: ‘How do you feel when you hear the sounds that I am making?’. As the reviewer for The Wire relayed, it became clear to the audience that they had ‘been welcome to participate in the noise making’ all along.

There is a strong political dimension to Wollscheid’s work, especially in his collaborative, participatory approach to making art and persistent questioning of authorship. Wollscheid grew up in Germany in the 1960s and 1970s and, like other artists of his generation, he felt the need to respond to a ‘permanent silence’ that pervaded the country, ‘silence about the past mainly, but also practical silence’. He says:

As a result, some youth started to experiment with attacks against that kind of silence. The RAF, the Red Army [Faction], as I understand them, were attacking the silence that permeated everything. That is part of my work. I couldn’t sit in a studio and silently paint. That’s ridiculous. I have to do something that I’m part of to experience some kind of response.24

Technical narrative

When discussing the work, Wollscheid tends to emphasise the interactive potential of Nonrepetitive rather than the specific technology behind it. However, the tools and processes used reflect the context in which the artist created the work, and Wollscheid was committed to using free and open-source technologies where possible.

The sound element of Nonrepetitive is created from a one-second sample of a recording of Wollscheid scratching his keyboard.25 The sample is then continuously and randomly transformed by a computer program. The interaction by online visitors causes the sound to change. The position of the line does not represent the audio output of the program, as a waveform might, but acts as a control interface where the position of points on the line triggers complex changes in the manipulation of the audio.

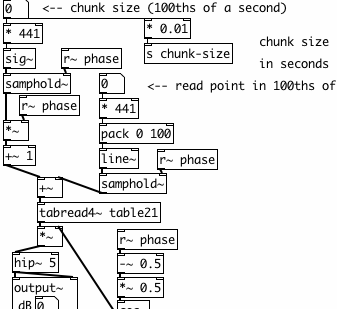

Fig.2

The Pure Data patch used in Nonrepetitive. The square boxes, or ‘objects’, contain functions. The objects are connected by patch cords which dictate the order in which the functions occur.

At the core of Nonrepetitive is a software application that allows multiple remote users to interact in real time with sounds as well as other remote users. The software application was created using the Pure Data (Pd) graphical programming environment (fig.2), together with plugins such as Adobe Flash (Flash) and other server-side technology.

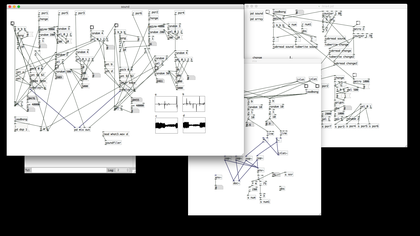

Fig.3

Screenshot of the Nonrepetitive Pure Data patch with all three windows open. The window on the left shows how the sound is manipulated; in the centre is the mixing window; and the window on the right displays the relation between the sound and the black line.

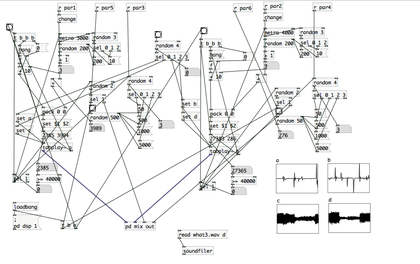

Fig.4

Detail view of the sound window from the Nonrepetitive Pure Data patch shows arrays and source audio files

Pure Data (Pd) is a C-based graphical programming environment that emerged as a later, open-source version of Miller Puckette’s highly influential software Max.26 In Pd, the usual lines of code that describe the functions of a program and how they interact are replaced with visual objects that can be manipulated on-screen. Wollscheid began working with Pd when he was looking to create a four-channel video artwork using a computer. He found that Pd suited his approach to programming because it uses a visual metaphor for coding rather than relying purely on text. He also highlighted the importance of Pd working in real time, as changes can be made while the program is running, allowing it to be used for live performances. Fig.3 shows the different windows that compose the Nonrepetitive patch in Pure Data. It shows how the sound is manipulated (shown in detail in fig.4), the relation between the sound and the line (Linie4.pd), and the mixing window.

The Pd patch loads an audio sample from an external file – in this case ‘read what3.wav’ – into the software. This is split and stored in four separate ‘arrays’, labelled a, b, c and d. The sound sample is the source material and the patch applies frequency modulation, randomised control signals and automatic signal routing for the patch to create complex varying outputs in response to user manipulation with a mouse. To allow remote access for multiple users, the software was set up on a web server.

Alexander Keidel was instrumental in developing the web elements of the project, namely those using the Java programming language (Java) and Flash. Wollscheid chose to host the software on the mainstream German provider Hetzner. The patch ran as a single instance on the server; it was streamed from the server to users’ browsers via an Icecast object, a piece of software that allows multimedia streaming, developed in part to create internet radio stations. The user’s browser would receive the stream, decode it and play it back via the Flash plugin. The communication from the browser to the server uses the HTTP GET method to input the cursor movements of the users.27 The software Watch Dog also ran on the server, which would relaunch the patch in the instance of a crash or failure.28

Current condition

At the time of writing, Nonrepetitive is not available online. In his agreement with Tate, Wollscheid agreed to maintain the project for a fixed period between 2011 and 2012, a decision made due to the cost of hosting and maintaining the site. Wollscheid has suggested that the work could be recreated, and improved upon, using different tools and a new interface.29 While significantly changing the interface may change the experience of the work as it was commissioned, altering the technologies of production may provide a way of maintaining the experience of the work.

The artist still holds the Pd project as well as the individual objects used within Pd and a copy of the server-side files that ran the software on the web server. As part of this case study, conservator Chris King installed Pure Data in order to run the Pd patch supplied by Wollscheid and assess its condition. The first stumbling block we came across related to the use of external objects, which were not included in the main Pd download. However, as they were still available online we could download and install them so that the software could run. Even though we could not test the networked elements of the work, the fact that we could run the patch indicates that it would be possible to rebuild Nonrepetitive online, possibly with some alterations to the networked aspect.

The work depends on multiple technologies, each with distinct levels of risk for preservation and different impacts on the experience of the work. As an open-source programming framework with a lively community to support it, the Pure Data element is fairly low risk; it is still possible to open the patch and make any necessary changes to deprecated parts. Furthermore, historical components are still available online. The interactive and networked aspects, however, depend on the Flash plugin, which has been deprecated since 2020. If the work were to be remade, the functions performed by Flash – both in the case of the user interface and the audio streaming back into the browser – would need upgrading. Current versions of Icecast no longer rely on Flash for in-browser streaming and have moved to HTML5, which could potentially support the types of interaction required by the work. Any such action would depend on the artist’s approval and an evaluation of the results for online interaction.

In our first interview with Wollscheid, he explained that he did not have much opportunity to consider the legacy of his work in terms of conservation or preservation. This is, in part, because he understands his work as a way of understanding or investigating the social context in which it is made:

Whether there is a legacy to what I do, that’s a very, very tiny little fraction of what I do within everything that’s going on. I think that is almost vanishing. It’s not there. I don’t think there’s a legacy. I use my art as a means to find out little things about what is going on. That’s it. No hopes, no expectations.30

After our initial discussion, and in preparing the technical narrative for this text, Wollscheid was happy to consider what it might mean to have the work live again. He has kept the project in his archive and collaborated openly in sharing information about the production and life of the work.

Conclusion

It is fitting that Nonrepetitive, the last online work commissioned by Tate for the net art programme of intermedia works, bears closest resemblance to the first, Simon Patterson’s Match des Couleurs of 2000.31 Both rely on sound and its intrinsic ability to get inside a listener’s head and provide a texture against which a visual experience might be grounded. Both also use repetition: in Patterson’s case the sing-song vocal rhythm of someone reading the final scores in an imaginary competitive game (as would have been broadcast on radio), and in Wollscheid’s the repetition of sound itself, distorted, layered and multiplied. The biggest difference in the works, however, is that between the individual and collective experience of the ‘listener’. Nonrepetitive is designed to be ‘played’ collaboratively by users who interact with the linear soundwave on screen in real time. Even with today’s layered ‘songs’ produced on the video sharing platform TikTok, real-time collaboration through a simple interface and preloaded sound files is not possible. Apps such as Spotify’s Soundjam or PiBox get close in practice but are very different in spirit, designed for musicians with specialist knowledge of how to build tracks.

In spirit, then, the work perhaps bears more resemblance to the popular Flash-based game LineRider (released online in 2006), in which users draw a line that becomes the ‘track’ for an animation of a small figure on a sled. It might seem strange to compare Nonrepetitive to this earlier internet phenomenon: LineRider was not originally a sound game, nor collaboratively played. However, it has been used for visualising soundtracks and making music videos shared online, and its core action of manipulating a line on screen to change a composition, which is then shared with others, could be considered a precursor to Nonrepetitive. In Wollscheid’s work, the sound continues to mutate and evolve even when it is not being manipulated, suggesting a sense of endlessness, much like the white landscape into which the LineRider is cast.

Wollscheid’s decision to use the software Pure Data and to make his software code available online also speaks to another important feature of net art of this period: that repositories of shared code could be implemented in any number of other art works. Artists often made use of Pd for audio and Processing for visuals as open-source alternatives to expensive and proprietary tools such as Max.32 These visual programming languages recall the techniques of twentieth-century electronic music, where ‘sounds were created and transformed by small electronic devices which were connected via patch cables’.33 An example of this might be John Cage’s Variations VII (first performed in 1966), in which television and radio broadcasts, conversations recorded from telephones, and recordings of household appliances such as blenders or vacuum cleaners were manipulated by into a collage of sound. Nonrepetitive reimagines Variations VII for the internet, with the sound of the artist tapping on his keyboard broadcast to the net, with participants invited to manipulate the wire on which that sound seems to travel. In this way, Nonrepetitive both represents and produces anew.