A Map of Terrorism offers a coded analysis of the ways in which our identities are constructed, categorised and tracked as data. It forms part of Heath Bunting’s ongoing work The Status Project, which was developed with Kayle Brandon from 2004.1 The artwork is an image in the form of a PDF (Portable Document Format), which can be explored online or printed out to standard paper size A0. The page is hosted on irational.org – a server established by Bunting in 1996 that hosts art by members of a loosely defined collective of net and new media artists – and is accessible via a link from the ‘Intermedia Art’ pages on the Tate website.2

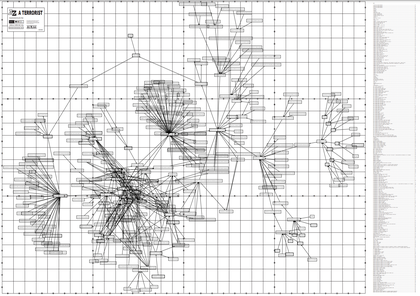

Fig.1

Heath Bunting

A Map of Terrorism 2008

Full map available as PDF at http://status.irational.org/map_of_terrorism/map_of_terrorism.pdf

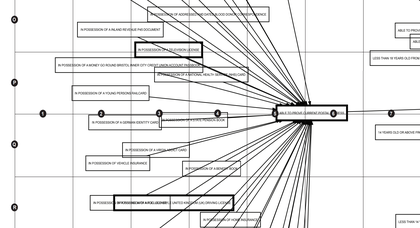

Fig.2

Detail of A Map of Terrorism showing a node reading ‘IN POSSESSION OF A VIRGIN ADDICT CARD’ connected to another stating ‘ABLE TO PROVIDE CURRENT POSTAL ADDRESS’

A Map of Terrorism resembles a spider diagram or flowchart, with multidirectional lines connecting various possessions, actions and consequences through which a person may be identified as a terrorist (fig.1). These identifiers include possessing providing training in forward rolls, being an environmentalist and glorifying terrorist acts. One box on the left of the map, for example, reads ‘IN POSSESSION OF A VIRGIN ADDICT CARD’ (a loyalty card for Virgin Megastores) (fig.2). This is connected to the box ‘ABLE TO PROVIDE CURRENT POSTAL ADDRESS’, which in turn leads to the ability to join the Bristol Public Library, and from there to accessing The Anarchist Cookbook, for which there are just two further steps before ‘ARREST FOR TERRORIST OFFENCES’.3 Through these categories and relational connections, the work aims to reveal how everyday language, requests for information, and protocols have their roots in political and social power dynamics.

Fig.3

Detail of A Map of Terrorism showing the A–Z design at top left

The design of the map, in particular the label at the top left, is a direct reference to the A–Z Maps published by Collins (fig.3). The black and white, DIY appearance of the flowchart is dictated by the data itself as well as from Bunting’s concept for the work. Rather than applying labels or categories to the data, Bunting ‘let the data structure itself’, retaining a flattened hierarchy of information.4 This approach towards the visualisation of data to allow for its ‘emergent nature’ can be connected to Bunting’s creative and activist background in DIY practices of mail art and street art.5

Bunting has described The Status Project as ‘an expert system for identity mutation’.6 The project was commissioned from Bunting and Brandon by Helix Arts in Newcastle and for exhibitions at the New Museum, New York, and the Banff Centre for The Arts in 2004.7 The work can be understood as an exploration into what Bunting refers to as the ‘system’, or the organisational structure ‘that governs the quality of living, compromises our freedom, supports discrimination, protects ownership, controls social mobility, etc’.8 Visualising and analysing this ‘system’ through a database (which at the time of writing had around 26,000 entries), Bunting explores who has social and political mobility and who does not. One of aims of the project is to illustrate that the self consists of multiple identities. Bunting describes the self in terms of three layers: ‘the human being’; ‘the natural person’ (the identity constructed through documentation); and ‘artificial persons’ (collectives, such as corporations).9 Some people, he explains, have access to more identities than others:

Most human beings have one natural person, but they fail to see their separate identities or the possibility of possessing multiple identities. Members of the elite possess several natural persons and control several artificial persons with skilful separation. ‘The Status Project’ began as a survey of these persons on a local, national and international level by producing maps of influence and personal portraits to comprehend the issues of identity and social mobility.10

The Status Project now forms the basis of much of Bunting’s work, which often explores ‘how networking, network language, databases and network infrastructure’ have become part of our everyday lives.11 According to Bunting, ‘you’ve got to look at the language, the protocols, not just of the internet transport layer, but of the user interfaces’.12 A Map of Terrorism, like the other fifty or so maps created as part of The Status Project, has been shown in different ways.13 It can been accessed as an image online, printed out and read, or printed out and displayed in galleries.14 In fact, the initial idea was that ‘people would walk around with maps in their pockets of the system as well as maps of the city layout’.15

Making and commissioning

A Map of Terrorism was launched on Tate’s Intermedia Art pages in 2008. It was commissioned as part of a wider programme called ‘Critical Gestures’, along with two other works, the reenactment of Festival of Misfits (retitled for the 2008 iteration as the Festival of Missed Fits), a newspaper work from 1962 by Gustav Metzger, and We Come from Your Future, a sound art series and public encounter by Ultra-Red.16 In an essay reflecting on this programmatic theme, the philosopher Sadie Plant considers how the three works draw on the themes of ‘flights of migrants, the lines they traverse, the crossings they make, the intersections they produce, the systems of surveillance and control they provoke, contest, and break’.17

Bunting’s map is based on a database he created using the UK Terrorism Act 2006.18 From this he pulled out the references to terrorism, which are listed in an index on the right-hand side of the map. According to Bunting, these references fall into three groupings: ‘performing an act of terror; membership of all of the prescribed terror organisations in the world; and then any mention of terror’.19 These references can be found as nodes towards the right-hand side of the map; on the left are what he refers to as ‘clusters of normality’, such as getting a supermarket loyalty or a library card. Bunting was interested in showing the ‘bridges’ between everyday situations where your information might be requested and what information the government might link together in order to define someone as a terrorist under the UK’s Terrorism Act of 2006.20

The work was informed by Bunting’s experiences of being investigated for suspected terrorist offences.21 In 2002, he was commissioned by Tate to create BorderXing, a work in which he and his collaborators crossed borders in Europe without a passport and demonstrated to others how to do the same.22 These actions and others brought attention to Bunting from UK border control and the police. With the commission of A Map of Terrorism in 2008, he saw an opportunity to respond: ‘If could get the Tate to stamp my work, I could then create this clash between intelligence services and culture’.23 Bunting therefore considered his work with Tate to be a political action, ‘play[ing] chess with the intelligence services’ by drawing on the power of another state funded institution.24 With the idea of a potential commission in mind, when Bunting was next stopped by UK border officers – a regular occurrence in his travels as an artist, given he was often questioned for having little luggage and carrying a hacked mobile phone charger with wires exposed – he retrieved the map from his pocket.25 He explained that it was related to ‘a commission from the Tate. It’s about how you’ve set me up. You framed me as a terrorist with a bomb. I’m not quite sure about this legal definition’.26

Reception and interpretation

A Map of Terrorism aims to reveal how the language and protocols we interface with daily are rooted in political and social power dynamics. It was intended as a usable guide, or map. It is therefore both an analysis of systems, relations and connections and a means to share this information with others. As Marc Garrett, Co-Founder of gallery Furtherfield, has summarised, ‘Bunting’s work expresses a discipline conscious of agency, autonomy and enactments for self and collective empowerment’.27 What he uncovers is shared, ‘leav[ing] the paths he has discovered wide open for others pass through’.

A Map of Terrorism also acts as a form of social network analysis. It illustrates, by way of direct visual links between different status identifiers, how recognised forms of identification, such as proof of residence or a fixed address, can allow some people to move across different social groups and conditions, while for others social mobility is restricted. Class is one aspect of this on which Bunting has reflected: ‘I come from a working-class background and you’re not allowed to talk about aesthetics. You can be a bad troublemaker, that’s it really. To kind of break that blockade, you have to make your own media.’28

In her essay published alongside the work on the Tate website, Sadie Plant considers the discrepancies that Bunting ‘unearths’ in the constructions of our identities by ‘state bodies and corporations with which they interact’. For example, how it is illegal to promote terrorism by ‘wearing a jihadist T-shirt’ and yet easy enough to purchase the T-shirt. Drawing a parallel between Bunting and the American artist and member of Critical Art Ensemble Steve Kurtz, Plant reflects on the contradiction that the nations these artists both operate in – the USA and the UK – ‘have defied international law to use violence in pursuit of their own political goals. The very freedoms they claim to protect are precisely those they undermine’.29

Other interpretations and analysis of the work consider it within the broader context of The Status Project.30 Garrett, for example, places Bunting’s work in the context of other hacktivist artists who analyse and respond to the increase in surveillance culture (for Garrett, the internet was a successor to Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon, called the ‘Netopticon’).31 Ida Hirsenfelder, meanwhile, notes how Bunting and other artists working online remain committed to present their offline work ‘using the same logic, advocating that hacking of social space is not only possible online but also in other, material realities’.32

The artist’s practice

Heath Bunting is an activist, artist, hacker, programmer, environmentalist, educator and one of the early founders of net art.33 Bunting began working as an artist in the 1990s, during a period of recession in the UK. One of the consequences of the economic crisis was the ready availability of discarded or unused computers, which Bunting began to use in his work:

There were lots of computers lying around in skips on the street. I rekindled my interest in computers and would do projects on the street with these systems… [that] you just had to plug in again because they’d been so hastily decommissioned. A whole tax department would be shut down by the austerity measures of the Conservative party at that time and just chucked out in the street, it wasn’t even recycled. You could do quite interesting projects with those.34

Bunting moved from Bristol to London in 1994, where he started a bulletin board system (BBS) called Cybercafe, ‘dedicated to arts and technology’.35 For one Cybercafe event that year, Kings X Phone-In he posted the numbers of public telephone booths in Kings Cross station, London, along with a number of prompts, including calling one of the numbers and chatting with whoever answered and gathering at the station to watch the reaction and interact with callers.36 He describes the event in a report published to Cybercafe: ‘I arrived about three o’clock in the afternoon; the phones were already ringing. The market research woman from BT, who happened to be there, said “its very strange, the telephones have been ringing all day”. agreed that it was strange.’37

The event highlighted questions of networks and connection, and in this way could be understood as an extension of mail art.38 Josephine Berry emphasises this communicative potential in her interpretation, describing how the work imagined the public phone booth area as ‘not just an instrument of personal, one-to-one conversation but as a conduit for engineering encounters between “members of the public” and in this sense “earthing” the communications network in the local context’.39

When Bunting began working online, he used CompuServe, a ‘computer time-sharing’, or internet service that was known in the 1990s for its online chat and messaging forums.40 Working online gave Bunting an instant global reach and he soon became part of a series of discursive events and exhibitions around early net art, alongside such artists as Alexei Shulgin, Vuk Ćosić and Natalie Bookchin. Bunting founded irational.org in 1996 as ‘an international system for deploying “irational” information, services and products for the displaced and roaming’.41 Artists associated with the group include Daniel García Andújar, Rachel Baker, Minerva Cuevas and Marcus Valentine. Their projects often highlight the benefits of being classed as members of a particular identity, as well as the requirements for entry to that identity. For example, Rachel Baker’s TM Clubcard – Earn Points While You Surf 1997 attempted to turn a customer database into a genuine social network, and Student ID Card 2002/2006 by Minerva Cuevas/Mejor Vida Corporation produced student ID cards for the public (with the benefits afforded to those enrolled in academic institutions), so they might be ‘never-ending students of a better life’.42

Bunting has worked with language and protocols since beginning The Status Project. As well as the maps, which as ‘sub-sections of the system’ help provide a ‘sense of place and potential for social mobility’, this work includes ‘Identity Kits’ composed of ‘business cards, library cards, a national railcard, T-Mobile top-up card, national lottery card and much more’.43 He also runs identity workshops, intimacy encryption workshops and survival training.44

Technical narrative

Visitors can access A Terrorist via a link on Tate’s Intermedia Art pages. The artwork page opens in a new window or tab as a PDF on the artist’s website, and a map fills the browser window. On the Intermedia Art page, there is a short text under the link to the artwork: ‘The map is available as a PDF and you will need Adobe Reader to view the project. Use the zoom function to examine detail and use the A–Z references to the right of the map in order to pinpoint the position of individual entries.’45

By using PDF, Bunting ensures that the map can be easily printed as well as navigated online, with zoom functionality for exploring the connections in detail. Bunting uses a coordinate system to locate specific characteristics in the diagram, much like the A–Z maps he references in the map’s label.

The source of the diagram is a MySQL database coded by Bunting to be non-hierarchical and unstructured. He used a script that pulled out all the database entries mentioning ‘terror’ and imported them to GraphViz, an open-source graph visualisation software.46 Graph visualisation is used in different areas of knowledge, from software engineering to web design, to represent structural information as diagrams and aid data analysis. Bunting framed his choice of software in relation to his community ethos: ‘I’m from this idealistic, free software, open-source kind of culture – DIY – and to use anything other than Graphviz would be seen as heretical or somehow corrupted’.47 Bunting used Neato, one of the main graph layout programs within the GraphViz package, to create the diagrams. Neato creates ‘spring model’ layouts, which place nodes in space according to the laws of physics rather than according to preset hierarchies. The distance between nodes depends on their connections with the rest of the data being analysed. It is an appropriate choice for the type of unstructured data Bunting was working with, the layout described by Graphviz as ‘the default tool to use if the graph is not too large (about 100 nodes) and you don’t know anything else about it’.46 Bunting made minimal changes to the default layout, choosing to keep the diagram in black and white, although other maps in The Status Project use colour.47

The drawings created in Graphviz can be exported into several different formats. In this case, Bunting used Scalable Vector Graphics (SVG), an open format for vector-based images that can easily be imported to a page layout programme. By using a vector-based image, Bunting ensures the maps can be scaled or magnified without becoming pixelated. The A–Z logo, the location grid and the map legend were added in page layout, for which Bunting used Adobe Illustrator. The final file was created by saving the layout as a PDF.

Current condition

The formats and technologies used in the work are widely used, well supported and open, with no obvious risks to preservation from obsolescence. The PDF map is hosted by the artist on his own server, rather than on Tate’s website. Because the Map can be seen there in the context of The Status Project, this arrangement works well. For preservation purposes, Tate could store copies of the PDF file and the HTML code that describes the behaviour of the page, along with a description of that behaviour in natural language. It is important to identify the object of preservation: the Terrorist map linked to from the Tate website; The Status Project as it appeared in 2008; or The Status Project as a whole and the MySQL database behind it.

Taking the last-mentioned, wider view would mean creating snapshots of the database over time, as preservation copies, while allowing Bunting to continue to host, maintain and update his version. This approach would not result in an exact reconstruction of the 2008 map, as the data on which it is built would have changed, but it would address the spirit of the project in that it would be updated with new legislation and legal definitions, allowing the creation of new maps reflecting different moments in time.48

Conclusion

A Map of Terrorism makes visible the large, often invisible systems and technologies that emerge from the entanglement between the public and the private in contemporary society. It is part of a broader body of work by artists who interrogate the way in which identity production has been impacted by globalisation and the internet.49 These works explore how these technologies destabilise what Josephine Berry has called ‘the older order of identity production (nation, class, race etc.)’.50 In the same essay Berry writes: ‘Making art with (networked) computers almost unavoidably spotlights issues of information, identity, and globality. But this would be to formulate the encounter as almost accidental, when so often it comprises the very motivation behind certain artists’ decision to work with this medium in the first place’. The themes explored within A Map of Terrorism remain highly relevant with a growing awareness of, and attempts to resist, the assumptions and prejudices baked into the algorithms that govern the use of personal data.51 In this text we have attempted to give a sense of the context in which Bunting was working and also the way in which the technologies used are integral to the project, including the way in which the work is rendered. In something as unstable and mutable as the nodes the project describes, it is a welcome irony that in the use of a PDF A Map of Terrorism forms one of the most stable outputs among the Tate net art commissions.