Le Match des Couleurs is an artwork and webpage by Simon Patterson that plays on the arbitrariness of coded language systems by combining two typologies: colour on the internet and football leagues. One is a coded system designed to be read by machines and the other a simple but evocative list. Until 2021, the work could be launched from Tate’s Intermedia Art pages.1

On the first screen of Le Match des Couleurs a grid of colour swatches appears (fig.1). Clicking on any of these squares launches a new window filled with the colour magenta (fig.2). At that moment, the audio begins, in which Eugene Saccomano (1936–2019), a French radio journalist and football commentator for the radio station Europe 1, reads a script written by Patterson. Saccamono narrates the scores of imagined games between teams in the French football league, followed by the name of the colour you see on screen and its hexadecimal code. For example: ‘Voici, Le Premiere Division; Auxerre 1, Equivalent Hexadecimal, Magenta CE007B; Bastia 0, Equivalent Hexadecimal, Magenta DE5AAD’. The whole sequence finishes with the word ‘Voila’.2

Fig.1

Landing page of Le Match des Couleurs 2000 by Simon Patterson, featuring a grid of colour swatches

© Simon Patterson

Fig.2

Subpage of Le Match des Couleurs 2000 by Simon Patterson. Clicking anywhere on the landing page takes the viewer to a magenta screen, originally accompanied by an audio track.

Every colour on the grid on the first page of Le Match des Couleurs is labelled with its representation as hexadecimal (hex) code. Hexadecimal code (where there are sixteen digits used, numbered from 0 to 9, followed by the first six letters of the alphabet, A to F) is used in computer programming to translate binary code to a form that can be more easily read by humans.3 In HTML, colours are described in hexadecimal code that takes the form #RRGGBB (RR= reds; GG = greens; BB=blues), so #FF0000 is the purest red (with the red at the highest value, F, and the green and blue at the lowest value, 0); black is #000000, white is #FFFFFF. Patterson’s decision to combine this coded system with another, the division of football teams into leagues and set matches, can be understood as part of his ongoing interest in the absurdity of juxtaposing unrelated groups or typologies.

Accompanied by the voice of Saccomano, the animation moves slowly through a range of colours, gently fading from one to the next in the order of the colour grid shown on the initial screen. Patterson describes how the ‘colours go from dark to light and bleach out almost to white in colour, before they start to fade in again and you realise the colour’s changed [...] you have a visual sense of it being a wave’.4 There is no option to pause, play or skip forwards; the only possible function is to close the window and return to the Tate homepage.5 Patterson describes this limit on user participation as a ‘slightly mischievous critique of Web Art’, much of which, at the time, emphasised interaction.6 In contrast, Patterson chose to set the rules and let the experience play out: ‘I just thought it’d be quite nice to do something that you press a button and you click on it. Nothing else. It doesn’t do anything. It just does its thing.’7 In many ways it functions like a film on a loop.

Le Match des Couleurs is the second of three works that make up Patterson’s colour match series. The first, Color Match 1997, is an audio work created with sound designer and artist Zoe Irvine in which Tim Gudgin (1929–2017), the football results announcer for BBC’s Grandstand and Final Score, reads from a text written by Patterson. It includes the names of every football team that has ever played in the English football leagues, the scores of imagined matches and the names of Pantone colours (the international standardised colour reproduction system used by printers and designers). One excerpt, for example, reads: ‘The FA Premier League; Accrington Stanley, Pantone Red, Late Kick-Off; Arsenal 2, Pantone Red 032 U; Aston Villa 1, Pantone Rubine Red U’. This first instalment of the colour match series was created for the exhibition Fantasy Football Art League in 7. It was subsequently released as a CD, in an edition of 50.

Le Match des Couleurs, also created in collaboration with Irvine, was initially shown as a video projection at artconnexion, Lille. Tate later commissioned a version of the work as part of its net art series, at which point the Pantone references were translated to hex code, a more relevant coding system for an online artwork. This version was also released on a CD and distributed in an artist’s book by Alec Finlay.8 The final work in the series, Colour Match 2001, was created as a screensaver and made available to buy in the Tate shop.9 Like the first two works, the screensaver fades between a series of colours and includes a narrative voiceover. John Cavanagh, football announcer for BBC1 Scotland, reads the names of all the teams in the Scottish football league, imagined scores, followed by code numbers of coated Pantone colours, for example, ‘Heart of Midlothian 1, Pantone Orange 021 C; Hibernian 2, Pantone Warm Red 1585 C; Inverness Clachnacudden, Pantone Warm Red, Late Result’.10

Making and commissioning

Le Match des Couleurs was one of the first pieces of net art works commissioned by Tate, along with Graham Harwood’s Uncomfortable Proximity in 2000. Sandy Nairne (Director of National Programmes, 1994–2002) announced the commissions on the Tate’s website: ‘Both artists have been commissioned simultaneously with a view to creating a dialogue of the interactive nature and possibilities of web art, exploring the relationship between the virtual and the real object and the role of the museum and the Internet in contemporary art’.11 The first commissions therefore include one artist who had experience of working with online technology – Graham Harwood, as part of the collective Mongrel – and another who was new to the medium, but who had works in the Tate collection.12

The piece was commissioned by Matthew Gansallo (Senior Research Fellow, Tate, 1998–2000), who described his interest at the time in bringing net art together with ‘work that we can readily identify as fine art – paintings, sculptures, representation’.13 He compiled a list of artists, including Patterson, who had never made work for the web, but whose art had the potential to ‘engage the audience’ in thinking about the internet as a tool for artists to use. Gansallo was particularly interested in the way Patterson played with the ‘innuendo of use of technological systems’.14 When Gansallo approached the artist about a possible commission, Le Match des Couleurs already existed as a video projection. Patterson proposed that this work could be translated into an online form. To achieve this, Patterson worked closely with Tom Betts (Web Editor, Tate, c.1997–2001).

Reception and interpretation

Le Match des Couleurs explores the absurdity of standardised systems and codes. Patterson describes how such systems can serve to muddle or destabilise the meaning they attempt to fix:

You’re trying to nail the meaning to the work and the work is shifting in relation to the meaning. So, as soon as you apply a name to something or you attribute something in a verbal language, that has already shifted in terms of our collective understanding of what that means. So, it’s just about the way that language is always in a state of flux. The meaning is always in a state of flux.15

Patterson also related Le Match des Couleurs to his experience of synaesthesia in the way it explores the internal alignment between things, people and ideas with visual phenomena such as colours.16

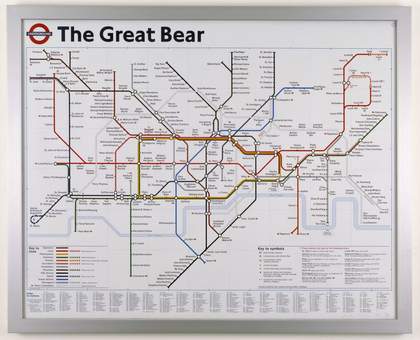

Fig.3

Simon Patterson

The Great Bear 1992

© Simon Patterson and Transport for London

The work acts as an archive, Patterson explains, in the way the list-like narrative records something that could become obsolete: ‘For me, it was the idea of memorialisation. If you’re evoking the names of all the teams that ever played in a league, then you’ve got some interesting names; teams that don’t exist anymore, like Middlesbrough Ironopolis. It immediately evokes a sense of lost industry.’17 The same memorialising function is present in other works by Patterson, including The Great Bear 1992 (fig.3), for which the artist redesigned the London Tube map using categories such as ‘engineers’, ‘footballers’ and ‘sinologues’ (Chinese scholars), to name the stops on each line.

After the commission was launched on 12 July 2000, responses to the work mentioned the slow loading speed of the image, both as a conceptual and technological point. In Tate’s institutional magazine, Paul Quinn wrote that Le Match des Couleurs exploits the inherent delays of the internet, as ‘a slow connection makes us contemplate the evolving pixels like specimens under glass’.18 In an essay commissioned for the Tate website, writer and artist Matthew Fuller describes a similar effect in ‘the pixels shifting in formation across the screen to different values’.19 These reflections record an experience of the work in the context of the internet in 2000. It also reflects Patterson’s interest in delays or gaps in understanding, which Gansallo describes as ‘the waiting and expectation of the computer and the internet: when you click on something and you wait for something to come up’.20 Fuller’s text places the work in an art-historical context, first in relation to the creation, circulation and standardisation of paint in the Renaissance, and secondly by creating a parallel between Patterson’s odd pairing of two coded systems and the ‘contradictory, awkward, random, juxtapositions’ of things, objects and ideas in the work of the Surrealists.21

At the time, there was some criticism of Tate’s selection of Patterson for a net art commission, rather than an artist more familiar and engaged with the internet. One reviewer for Metamute compared Patterson’s approach with that of Graham Harwood, who was commissioned by Tate at the same time.22 Patterson’s artwork is described as blending ‘perfectly with the Tate website’s monochrome décor to produce the seamless countenance of Britart cultural unity... fit[ing] snugly into this framework provided for them by the art museums’ nineteenth century agenda’.23 By comparison, Uncomfortable Proximity turns the Tate collection inside out, revealing ‘a political history of the art museum as an instrument of social engineering’.24

Fig.4

Simon Patterson

Cosmic Wallpaper 2002

© Simon Patterson

The artist’s practice

Le Match des Couleurs and the other works in the colour match series combine systems of knowledge from one discipline or social class with another. This concern for juxtaposition, categorisation and social groupings is seen in many of Patterson’s projects. In Cosmic Wallpaper 2002, for example, Patterson renamed constellations of stars with a history of the band Deep Purple (fig.4).25

Patterson’s work was included in the exhibition Freeze, organised by Damien Hirst in London Docklands in 1988. He was nominated for the Turner Prize in 1996, for which he displayed First Circle, an 18-metre wall-based ‘rainbow spectrum’ superimposed with a map of the solar system.26 It was shown at Tate as part of an installation of three yachting sails named for Laurence Sterne, Currer Bell (Charlotte Bronte’s pseudonym) and Raymond Chandler, drawing upon ‘puns on shipping terms and equipment (stern, bell, chandler) and the nature of making art’.27

Technical narrative

The online version of Le Match des Couleurs is based on the earlier video installation. It was adapted to the web by converting the video to a Flash animation and translating the Pantone references to the hexadecimal code. In 2002, Flash was the most common way of displaying video on a browser, as video files were still too large to download and video playback on the browser was not implemented. The adaptations to the web were performed by Tom Betts who, as the first web editor at Tate, had worked on the design of the first Tate website.28

On experiencing the artwork as users, we identified some unexpected behaviours. For instance, the animation always begins with the same shade of magenta and related audio, no matter which colour is selected from the initial grid. Although we thought this may have been an error, interviews with the artist confirmed that this was the way he had designed the work. We also noted that the Shockwave Flash Movie (.swf) file presented as a bar of colour at the top of the browser window, rather than filling the full screen. In this case, we knew the intended behaviour was for the colour to fill the browser window and screen.

We wanted to understand how the page was built and coded. We began by using the developer tools on our browsers to look at the code for the pages. The computer scientist Emma Dickson undertook further analysis of the .swf file using a tool called Trillix.29 Like most webpages, then and now, Le Match des Couleurs uses Hyper Text Markup Language (HTML) to describe the structure of a webpage and JavaScript and Cascading Style Sheets (CSS) to describe how HTML elements are to be displayed.30 To understand why the .swf file was not displaying correctly, we needed to consider the site’s HTML elements, which are defined by ‘tags’, sets of characters constituting a formatting command for a webpage.31 For example, <table> defines a table, <p> defines a paragraph and <h1> to <h6> defines text as a heading.

The table on the first page of Le Match des Couleurs was created using the <table> tag, but the layout is uneven. Each cell on this table contains a subtable, which when clicked calls a JavaScript function that launches the page with the .swf file. The code used to embed the .swf file in the webpage is reproduced below:

We can see from this code excerpt that the ‘test.swf’ file is defined to display at 100% of the width and height of the page, scaling to an exact fit, with a background colour of #ffffff, or pure white. It also links to a download page for a Flash plugin. The <embed> tag defines a container for an external application, in this case a Flash application, which would be needed to display the .swf file.

Like any other standard, HTML has evolved over time and some tags have been interpreted in different ways by browsers or been superseded so that browsers no longer interpret them at all. We suspected the .swf sizing issue was the result of changes in browser implementation of the HTML tags between 2001 and 2021. It is a fair assumption that when the work was first made it would have displayed correctly in most browsers, given that there is no mention of the error in the written accounts of the work. We knew the issue was with how the dimensions of the .swf file were being defined, which in this case was done in relation to the <embed> tag. The tag had been initially proposed by the developers of Netscape in 1995, but was not made part of the HTML standard until HTML5 in 2008.32

Emma Dickson noted that the page used Extensible HyperText Markup Language (XHTML) 1.0, a standard from 1999 that does not officially recognise the <embed> tag. By removing the ‘declaration of standard’ from the HTML code, the browser will render the site using HTML5, allowing the tag to be displayed as intended. Dickson realised, however, that doing so brought up the question of the work’s original appearance: ‘Did it ever display the embedded element full screen using the XHTML-1 Transitional format?’ In the report, they provided some potential answers:

Browsers change the way they parse formats and enforce strictness over time so it’s possible that as HTML5 was adopted the browsers changed the way they enforced different HTML standard declarations and started enforcing rules they hadn’t previously. This discrepancy will need to be addressed if a restoration is ever undertaken, either by updating the file format or viewing it through an emulator that would correctly render the XHTML-1.0 Transitional format.33

The other major challenge to the long-term preservation of this piece was its use of Flash. The application was still supported when we started the project, but was discontinued in December 2020, after which Flash/.swf files were removed from Tate websites as a security measure. This raised a further question: is there a way of supporting access to Flash files online while removing the associated security risks?

Research is currently being undertaken by the Emulation as a Service project at the University of Freiburg. The project team proposes scaling the use of emulation – using an application to imitate the behaviour of another – to support the running of obsolete software, including Flash, for cultural heritage organisations. Other approaches to safely supporting Flash are summarised by Dragan Espenchied in an editorial for Rhizome. The author lists tools including Rhizome’s archiving service Conifer and the browser-based Flash emulator Ruffle, as well as the creation of thorough documentation, such as that proposed by Constant Dullaart and Robert Sakrowski.34

Sarah Haylett, the Archives & Records Management Researcher on the Reshaping the Collectible project, recorded Tate’s Intermedia Art pages, including the launch page for Le Match des Couleurs, as well as the work itself, using Webrecorder (now Conifer). These recordings will be available as Gallery Records.35 Further documentation was produced in the form of interviews with Simon Patterson and Tom Betts, and through a detailed technical description of the work.

Conclusion

One of the first works of web-based art commissioned by Tate, Le Match des Couleurs could be considered as a memorial to the systems that have built our culture, be it through listing defunct football teams or referencing the colour standards that become obsolete with changing web design practices. The artwork was launched in 2000, four years after the first iteration of Flash was released as Macromedia Flash 1.0 and when net art was still developing as a genre. Audiences might have wondered, therefore, if it was possible to have an aesthetic experience via an internet browser window or how such an artwork might function. By deliberately making his work non-interactive (clicking anywhere on the colour grid sets the work running), Patterson created a contemplative and time-bound experience of shifting colour fields. The work's comparison to a screensaver in the press release was appropriate. It is also telling that one of the reviews for the work published at the time mentions that Tate had produced a colour range for the DIY store B&Q. Unlike an actual football match, Le Match des Couleurs leaves it up to you, the viewer, to decide how long to spend staring at it, letting the colours compete for your attention.