BorderXing Guide is an art project accessed via a website created by Heath Bunting between 2002 and 2003 to document his experiences, and the experiences of his collaborators, crossing borders in Europe without documentation.1 The website also served as a resource demonstrating how others might do the same. The artwork webpages are hosted on the artist’s website, irational.org, and are linked to on the Tate’s website, initially under the banner of ‘net art’, and from 2008 within the Intermedia Art pages. When the project was launched, access to the BorderXing Guide website was possible only from authorised client computers; today it is open to all internet users. The webpages contain an archive of documentation collated by Bunting and others from attempts to cross borders in Europe without travelling via official checkpoints. The website also includes background to the production of the work such as contracts and budgets, narrative guides and recommendations for travellers. The website was launched in 2002 and updated with records of border crossings and commissioned performances until 2007.

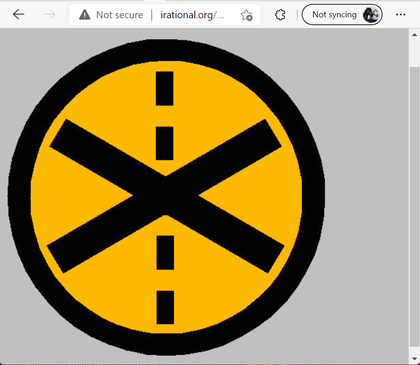

Fig.1

Landing page at http://www.irational.org/borderxing/

Fig.2

Listing of borders at http://irational.org/cgi-bin/border/route/route.pl. Those not yet attempted are coded in orange; those successfully crossed are coded in green (if overland) and blue (over water).

The website’s landing page shows a black ‘X’ in a yellow circle with a black border, set against a grey screen (fig.1). Clicking on the ‘X’ takes you to a second page, where the contents of the artwork pages appear as a bulleted listed of links in black Times New Roman font, again set against a grey background. One of these links to the ‘routes’ page, which displays a chart of the routes taken by Bunting and friends, including those attempted or scoped and those successfully crossed (fig.2). These are graded for difficulty between 1 and 6. Clicking on a route takes you to a page that details the dates, intention and equipment needed for the crossing along with a textual and photographic narrative of the journey and concluding thoughts or recommendations. For example, on a crossing between Hungary and Austria in 2006, Bunting writes: ‘Learn to vary your speed as required. Move slowly and experience fast on the border – do not rush. Use tall crops for cover. Cross lines of drift (paths, rivers, roads) at 90 degrees using a high level of caution.’2

Fig.3

Example of the photographic documentation of the crossing between France (l’Hospitalet Pres l’Andorre) and Andorra (Soldeu)

Source: http://irational.org/borderxing/fr.ad/day02_lake01_kayle_brandon01.jpg

There are also links to maps or additional information on some of the route pages. Photographs capture various stages of the journeys, from cooking porridge and falling over to stopping to view the landscape (fig.3). Journeys were undertaken solo, with another person or – more rarely – as part of a group.3

At the time of writing, the website is fully accessible anywhere in the world. However, when it was initially launched in 2002 it was only openly accessible to users in certain countries. In Europe (including at that point the United Kingdom), the United States, Canada, Australia and New Zealand only ‘authorised clients’ could view the work. People or organisations could apply to Bunting for authorisation, so long as they had publicly accessible internet. Clients and countries with full access – from education and cultural institutions, such as Tate, to individuals and businesses, such as Easton Internet Cafe in Bristol – are listed under the ‘client’ section of the website.4 Regarding this authorisation process, Bunting explained that ‘countries which are normally difficult to enter get blocked apart from specifically listed locations, countries which are more welcoming get free access. It’s a simple ironic reversal’.5 Placing conditions or rules on access highlights the distribution of power and mobility. In Bunting’s words, it was about ‘trying to reverse the freedom of movement we have in the West and the restrictions we place on people from other places’.6 The authorisation requirement was also, as curator Honor Harger observed, a challenge to ‘the supposed liberties that accompany the concept of the Internet as a borderless space’.7

In the ‘Production’ section of the website, Bunting published administrative and financial information about the commission. There is a detailed budget, invoices and contracts, including those between Bunting and Tate.8 By sharing this information, Bunting disrupts the balance of power, which is usually weighted towards the commissioning party rather than the artist. Organisations such as Tate traditionally keep this information private, or not easily accessible to the public. Publishing such information holds the institution accountable for their hiring and commissioning practices and gives artists the opportunity to better advocate for themselves and their work. This administrative transparency was shared by other net artists. Andy Deck, for example, another artist commissioned by Tate, provided a link to his commissioning contract on Screening Circle.9

Making and commissioning

Bunting was invited by Jemima Rellie (Head of Digital Programmes at Tate, 2000–07) to submit a proposal for a work that could be displayed on Tate’s website. In an email to Bunting, Rellie explained that Tate was encouraging proposals that ‘respond to the historical context of network art; or, respond to the context of Tate as a media and communication system; and that might involve significant elements of interaction’.10 Bunting replied with a proposal to develop his ongoing project A guide to crossing borders in Europe.11 He reasoned that working with Tate would give him the opportunity to reach a broad audience, since ‘the Tate is an attractive tourist location for many foreign visitors many of whom will have difficulty in obtaining visas to enter the uk the border crossing guide could be useful… marketing’.12 On the project’s budget, available on the BorderXing Guide website, Bunting notes that he believed the artwork could be used to ‘provide concrete information’ for ‘activists, asylum seekers, eastern europeans without visas’.13 A launch event was held online and at Tate Modern in October 2002, with a seminar by Heath Bunting, Armin Medosch and Florian Schneider.14

Advising Tate on the selection for its net art commissions, artist Matthew Fuller reflected on the parallels between Bunting’s proposal and the work of artists such as Ian Hamilton Finlay and Richard Long, which often use the landscape as material or as an environment for a journey or narrative. He noted how Bunting extends this approach by including in his work ‘an interrogation of the political, economic and juridical composition of landscape and travel’.15 BorderXing Guide was co-commissioned by Tate and the Museum of Modern Art Luxembourg (MUDAM) and was launched on institutional websites by 30 June 2002.16 Both organisations paid Bunting £4,500 and, in return, leased the work for their websites for five years.

Reception and interpretation

The work can be understood as an extension of land art, as live art and performance, and as political activism. It is rooted in Bunting’s personal experience (and the experience of his network of friends and collaborators) of border issues.17 He has described how BorderXing Guide was a challenge to restrictions on the freedom of movement at the time:

I was looking more at the founding mythology of the EU of open borders and freedom of movement of people, products and capital and the reality on the ground. Also, this close connection between natural landscape and legal state boundaries. It’s really a good excuse just to roam around Europe and climb some mountains. Feel like I was doing something naughty, which I was actually because that got me into being classified as a terrorist, actually.18

The internet acted as a means of production as well as a means of distribution for BorderXing Guide. Bunting has described the sense of mobility that creating work online gave him, using a server as a studio space: ‘I’d go to an internet cafe, log into my server, do some writing, do some emails, make some webpages, upload some pictures, log off and go somewhere else.’19

In an essay contextualising BorderXing Guide on Tate’s website, Florian Schneider compares Bunting to a coyote, a term used in the border area between North America and Mexico for ‘the traffickers in migrants, who for a fee offer their knowledge of how to cross a state border without the usual paperwork’.20 Like a virtual coyote, Bunting collects and documents experiences and translates them into a manual for others. Schneider situates the work in the context of the increasingly complex network technologies (chip cards and biometric systems) at national borders at the turn of the millennium. The website was included in an exhibition of works at Hartware MedienKunstVerein, Dortmund, in 2006.21 It was shown together with related works such as Botanical Guide (presented as a booklet) and a DVD slideshow of photographs from the initial twenty-four journeys. The curators wrote that the project, with its access limited to those in particular places, exemplifies the idea that ‘the work wants information to be free, but recognises that it needs all kinds of protection to stay that way’.22

Bunting has also spoken about his experience in interviews.23 In preparation for an exhibition at Galerie im Taxispalais, Innsbruck, in 2007, he invited artist and writer Sissu Tarka to undertake a journey with him.24 In an article for Afterall, Tarka reflected on her experience of ‘virtually’ accompanying Bunting via messaging and sharing photos, placing their interaction within the context of site-specific performance and animation. She wrote: ‘I notice that our textual communication provides the means to explore the experience of a site, one simultaneously close and remote’.25

The artist’s practice

Heath Bunting is an activist and artist (or ‘artivist’26 ), hacker, programmer, environmentalist and educator.27 An early practitioner of net art, he is a co-founder of the artist-run Cube Cinema and Managing Editor with Natalie Jeremijenko of the magazine Biotech Hobbyist.28 Bunting is most closely associated with the server irational.org, which is an archive of his work and that of six other artists: Rachel Baker, Minerva Cuevas, Daniel García Andújar, Marcus Valentine and Kayle Brandon. The server and the projects and information hosted on it are described as ‘an international system for deploying “irational” information, services and products for the displaced and roaming’.29

Bunting has long been concerned with the political and environmental factors that structure lived experience and much of his work involves creating digital tools and protocols that can aid survival, such as manuals on how to plan your day, climb a tree, raid a skip or forage for food.30 Bunting’s daily route plans and his own experiences of being held for questioning when travelling can be understood as part of his ongoing practice of interrogating systems of control, access and information management. At the time of making the work, Bunting did not consider himself a net artist but claimed to have ‘network consciousness’.31

Technical narrative

The website is built exclusively with HTML and relies on techniques common to the late 1990s, such as the use of tables to create the layout of the page. This choice is consistent with the concept of the work as a tool and with Bunting’s preference for open-source software and standards such as HTML. The design of the page recalls earlier web browsers, with the use of the grey background and the Times New Roman font.32 By 2002, this visual language was already anachronistic.

The site is currently accessible online via the artist’s server. In part thanks to its technical simplicity, the page is handled correctly through browser-based quirks mode, even where web standards are not fully complied with.33 Quirks mode is intended to maintain support for HTML in websites built before the widespread adoption of web standards. The HTML elements and tags used throughout the site are still widely used and supported, so there is little immediate risk of them becoming deprecated. The simplicity of the site also means that the risk for preservation is low. Sarah Haylett, the Archives and Records Management Researcher on the Reshaping the Collectible project, used Rhizome’s web archiving service Conifer to record the Intermedia microsite, including BorderXing. The resulting Web ARChive (WARC) files are kept in Tate’s Public Records Collection. This means that, even if Heath Bunting stopped hosting the website, records of it could be used to rebuild the user-facing parts of the site.

Conclusion

BorderXing Guide is a significant work in the history of net art as well as in the history of land and performance art. It was a pivotal work for Bunting, both in that it defined many of his later projects and because of its material effects on his life: he is still regularly detained when crossing borders (legally and with a UK passport). Bunting describes his obsession with mapping the routes between two points – whether physical locations or virtual data points – as a survival skill, one necessary to evade difficult situations or to create new ways out.34 BorderXing Guide, with its architecture of authorised client access, takes the language of computer programming, in which protocols enable access to run routines, and brings it into the real world. Most importantly, however, is the activist gesture that Bunting made by proposing this work for the Tate’s net art commissions, resulting in Tate showcasing information which could be seen to run counter to national interests. The work thereby explores the role of institutions in securing borders, including those between genres or schools of art (performance art/landscape art), between ways of understanding art (finished object/ongoing project) and between art and life (what is in the museum/what is in the rest of the world).