In 2006, the artist collective Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries (YHCHI; Young-Hae Chang and Marc Voge) created two related net art works: The Art of Sleep and The Art of Silence. Both take the form of animated films comprising black text on a white background, with no other colour or imagery; both are accompanied by a jazz-influenced soundtrack. The works were acquired by Tate in 2018 and can be experienced online via their respective artwork pages, linked above. They are currently on display as part of the Media Networks display at Tate Modern, London, in which audiences are directed to the net art works via a QR code on the wall of the gallery.1

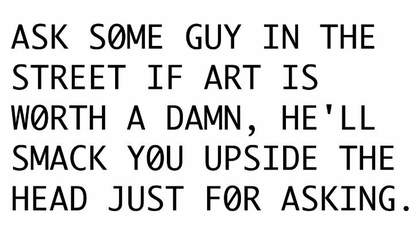

Fig.1

Still from THE ART OF SLEEP 2006

Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries (Young-Hae Chang and Marc Voge)

© YOUNG-HAE CHANG HEAVY INDUSTRIES

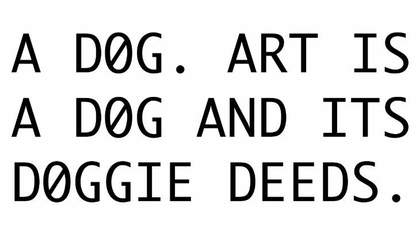

Fig.2

Still from THE ART OF SLEEP 2006

Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries (Young-Hae Chang and Marc Voge)

© YOUNG-HAE CHANG HEAVY INDUSTRIES

The Art of Sleep is a stream-of-consciousness narrative of an individual’s thoughts as they lie in bed, kept awake by the whining and barking of a nearby dog. The twists and turns of the narrator’s thought patterns have an anxious, humorous, repetitive tone. First, they focus on the irritation caused by the dog and the futility of its whining. This soon leads to an ‘earth shattering discovery’ about the meaning of art and the art world – that it, too, is futile, and that anything can be art (figs.1 and 2). The narrator’s thoughts become more passionate and fast-paced as they become excited by their discovery (‘The entire history of art is a lie!’) and their plan to outsmart ‘the bastards’ – the critics and art dealers who perpetuate and benefit from it. The narrator begins to test their theory (‘Apples are art; Asses are art; Axes are art’) and the dog’s barking ceases. After a short while, it starts again. The narrator concludes by saying, ‘I’ve got to get up early and start this damn Tate commission’. The work’s soundtrack is a relaxed jazzy cymbal beat with a synth melody and occasional samples of keyboard and double bass.

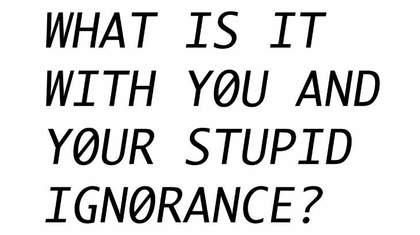

Fig.3

Still from THE ART OF SILENCE 2006

Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries (Young-Hae Chang and Marc Voge)

© YOUNG-HAE CHANG HEAVY INDUSTRIES

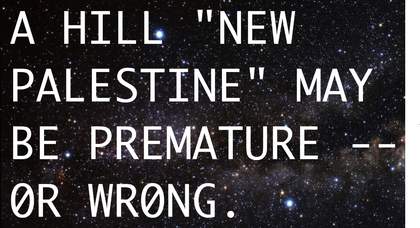

Fig.4

Still from THE ART OF SILENCE 2006

Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries (Young-Hae Chang and Marc Voge)

© YOUNG-HAE CHANG HEAVY INDUSTRIES

The Art of Silence takes the form of an interview with Chang and Voge about The Art of Sleep by Jemima Rellie, who commissioned both works in her role as Head of Digital Programmes at Tate from 2000 to 2007. Each participant in the conversation is given a different, computer-generated voice. Rellie asks the artists a series of questions about their work and influences. The conversation at first appears to be an argument between the artists, but as it evolves it becomes recognisable as a discussion about the processes of validation and education in the contemporary ‘art world’ (figs.3 and 4).2 Throughout, a pacy soundtrack of drums, cymbal and synth accompanies the computer-generated voices of Voge, Chang and Rellie. It ends with Rellie singing ‘Funky Nassau’, a song written by Ray Munnings and Tyrone Fitzgerald and recorded by funk band The Beginning of the End in 1971.

Making and commissioning

The Art of Sleep was commissioned for Tate’s website in 2006 by Rellie, who had invited the artists to make a work that commented on the art world. The Art of Silence was a subsequent commission of the same year, also for Tate’s website, which evolved from Rellie’s invitation for YHCHI to take part in an interview. The Art of Sleep was first made accessible on Tate’s now-defunct Net Art pages in November 2006, and migrated in 2008 to its Intermedia Art microsite. In both locations, it was accompanied by the essay ‘An Ornithology of Net Art’ by artist and co-founder of Rhizome, Mark Tribe.3 The Art of Silence was presented via the same pages, where it was described as an interview rather than an artwork. At the time of writing, both exist as videos, accessible both from the Intermedia Art pages and from the Tate artwork pages.

In 2006, the now unsupported Adobe Flash Player (Flash) versions of the works would open in a new web browser page from Tate’s Net Art pages, linked to from Tate’s homepage. In the Flash version, once the works began, they could not be paused or skipped back or forwards and the work’s running time was not visible; the only way to stop the work was to click ‘back’ on the browser window, type a different web address in the address bar or close the window entirely.4

Reception and interpretation

In both The Art of Sleep and The Art of Silence the artists share their ‘neurosis’ and ‘insecurities’ about feeling like ‘total outsiders’.5 Based in Seoul, they felt disconnected from the rapid changes taking place in the international art world. The internet was a way for them to show ‘that art can be made anywhere by strange people, such as ourselves, even in places like Seoul, South Korea’.6 However, despite making work on and for the internet, they also felt peripheral to the net art scene, in large part because they ‘didn’t do’ interactivity, which they considered a ‘driving force’ of net art.7 In 2001, YHCHI received a Webby Award for their website but were simultaneously criticised by some on the jury for resisting interaction and ‘algorithmic computation’.8 While the lack of interaction in their works made YHCHI relative outsiders from net art scenes, they were embraced by artists working in other spheres.

In ‘An Ornithology of Net Art’, Mark Tribe reasserts the artists’ credentials as new media artists and reflects on their success in the ‘mainstream art world’.9 He attributes this to the way ‘their work resembles older art forms, such as concrete poetry and experimental cinema’, as well as their use of ‘emotionally expressive voices and dynamic visual qualities [that] communicate across disciplinary boundaries’.10 Jessica Pressman, an academic with a focus on experimental literature, has further explored YHCHI’s relationship to ‘older art forms’. Pressman identifies modernist strategies in YHCHI’s work, comparing the minimalist aesthetic they employ with ‘avant-garde experiments in typography’ and the narrative style to the ‘manifesto tone of the modernist period’.11 She also considers the reading experience they create for their audience, describing how the onslaught of text and sound denies the ability for close reading. The combination of this style and approach leads Pressman to frame the work of YHCHI as an example of ‘digital modernism’. She describes this as a strategy in which the techniques and aesthetics of modernism are adapted to critique ‘a contemporary culture that privileges images, navigation, and interactivity over narrative, reading and textuality’.12 Pressman suggests this can be seen in YHCHI’s use of language – sometimes irritated, playful, explicit, and always personal – as well as in their ‘minimalist aesthetic’.

YHCHI considered their prevention of viewer interaction in the historic Flash versions of the works as a ‘dictatorial stranglehold on their viewer’.13 Pressman interprets this as resistance, as ‘an effort to remind the reader that the screen shields, and thus makes illegible, the coded processes that enable the text to appear on it’. Recognising a shift in user behaviour towards streaming content online, YHCHI decided to adapt their work into a video format that would not require Flash. This meant that the work could be more easily played on mobile devices, but also altered the user interaction so that viewers could now pause and skip through the film. This shift in approach was not unanimously welcomed. The artists recall one particular comment from a Harvard professor after he heard about this change: ‘Hey’, he said, ‘you just took out the most interesting element of your work’.14

The artists’ practice

Fig.5

Screenshot of WA’AD 2014

Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries (Young-Hae Chang and Marc Voge)

© YOUNG-HAE CHANG HEAVY INDUSTRIES

The work of Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries combines global languages, poetry, cultural and political comment and humour. Their aesthetic is simple. In The Art of Sleep and The Art of Silence they use Monaco typeface set against a white background and choreographed in rhythm with music, sometimes American jazz and bebop from the 1950s and 1960s, or their own compositions. The subjects of their work range from everyday scenarios to the cultural, social and political. These topics often take the form of a conversation that appears on screen.15 Samsung 1999, for example, tells the story of how the South Korean multinational brand changed the narrator’s life;16 Bust Down the Doors! 2000 is a fifty-five-second Flash animation telling the story of a house raid;17 and Wa’ad 2014 explores an Israeli-Palestinian utopia on Mars from the perspective of a Palestinian astronaut (fig.5).18

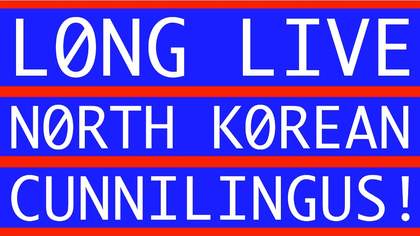

Fig.6

Still from CUNNILINGUS IN N0RTH K0REA (TANG0 VERSI0N) 2003

Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries (Young-Hae Chang and Marc Voge)

© YOUNG-HAE CHANG HEAVY INDUSTRIES

Language is seen by YHCHI as a vehicle to get ‘emotions out there’. In the context of the web, language ‘was the information super-highway’.19 They work in multiple languages, often aping or appropriating the language of advertising. This is both a celebration of mass culture and a reference to the effects of globalisation, political conflict and commodification. CUNNILINGUS IN N0RTH K0REA 2003, for example, is a fictional text which has supposedly been shared by YHCHI at the request of Kim Jong-Il.20 Within it, the North Korean leader promotes the leadership’s love and commitment to female oral pleasure (fig.6). This take on the dictator’s perspective of love (‘sexism is linked to capitalism’) can also be seen as a comic reflection on the experience of living under the threat of a potential nuclear attack.

Young-Hae Chang and Marc Voge met in Paris in 1997. Soon after, they formed a collective, appointing Young-Hae as the Chief Executive Officer and Voge as the Chief Information Officer. Attracted by the immediacy and global reach of the internet, which they have likened to ‘a convenience store open 24 hours a day, 365 days a year’, they set up yhchang.com to present their work.21 They have emphasised how showing their work mostly on their own website afforded them both independence and visibility: ‘All you need is your own website and an internet connection and you no longer need things like an artists’ studio. You no longer need to be in London’.22 The technical limitations of the internet in the 1990s shaped YHCHI’s work. As they point out, when they first started to make work, ‘the only way you could get yourself out there and make a statement, say you exist, was with words’.23 Images took time to download, likely slowing down a user’s experience of their works. Instead, through their ‘text-based movie[s]’, they could put their story on the screen in just a few seconds.24

Technical narrative

Both The Art of Sleep and The Art of Silence were created as online Flash animations (.swf) embedded on a webpage and hosted on Tate servers.25 Flash was a two-part system: the first was a graphics and animation editor (then known as Macromedia Flash) for content creation; the other was a player (then known as Macromedia Flash Player), which could play back that content on a computer or in a browser. YHCHI also used ActionScript in the work, a Flash-specific programming language initially added to enhance the options for animation, but which quickly evolved to support the creation of complex interactivity.

From a technical standpoint, the works are very similar and unless otherwise stated the text below applies to both The Art of Sleep and The Art of Silence. The artists began the process of making the works by testing the layout of the text on screen and choosing music to accompany it. The text was then laid out on a timeline in Flash, where the artists defined the speed of the text/image sequence in relation to the rhythm of their chosen music. They used AppleWorks for text editing and Sony Acid to compose the music.26 Since YHCHI work mostly on Apple Mac-based environments and Sony Acid is PC-based software, they eventually switched to Apple’s GarageBand.27 More recently, the artists have used Logic Pro, which is also an Apple product.28 For The Art of Silence, the voices of the three participants (Young-Hae Chang, Marc Voge and Jemima Rellie) were synthesised by a computer. The artists have described this process:

We used – if memory serves; this was 12 years ago – AT&T’s free text-to-speech online app... You’d plug into a window a limited number of words, and the app would offer to voice it with, among a few others, an ‘English’ accent. We’d record the resulting voice... the English ‘Audrey’ voice, that’s the one we used for Jemima Rellie, the curator of our Tate Online project. (By the way, at the time, and believe it or not, we recall Jemima telling us that the ‘Audrey’ voice sounded a lot like her.) As for Young-Hae’s voice, we used what’s now called the ‘Vicki’ voice on the Mac. For Marc we used what they’re now calling ‘Alex’. We added a MIDI version of ‘Funky Nassau’ for the singalong at the end. We synced the voices and the music on the Acid timeline, then exported it into MP3 and AIFF formats.29

The text and audio elements were combined using the Adobe Flash editor, and the resulting animation was exported as a .swf file. When setting up the two webpages on the Tate servers, the artists supplied the .swf files as well as the specification on how the animations should appear on the browser window – the size of the frame around the animation and that they should not loop.

The specificities of Flash influenced the look of the work. For instance, the text-based images that form each frame of the animation are vector-based and so can be resized, even by individual visitors on their own browser, without showing pixelation. The artists also designed the webpage so that the Flash animation started automatically when the page is opened, which is no longer possible on current browsers. Another aspect specific to these works was the lack of playback control: once the Flash file started to play the only option was to either let it play or close the window.

Current condition

The original, Flash-based versions of the two works commissioned by Tate and stored on the Intermedia Art pages of the website are no longer accessible from modern browsers. In 2017, Adobe announced that it would stop distributing and supporting Flash from December 2020.30 Since then, browsers can no longer play Flash files and block Flash-based content from running in Adobe Flash Player.31 The animations were removed from the Tate pages in 2021.

Until Flash’s ‘end of life’ in 2020, the films could be played in most browsers, provided the permissions to run the Flash player were enabled and the visitor to the site approved the playback. The works, like all content made with Flash-based technologies, have never been accessible on mobile phones or tablets, as the operating systems and browsers on these devices do not support Flash. Indeed, Flash’s decline is closely related to the advent of the iPhone and Apple’s decision not to support it on their mobile devices.32 The artists cited the lack of Flash functionality on mobile technologies as a major issue, particularly given that in South Korea, as in many other parts of the world, people were increasingly accessing the web via mobile devices.33

Unlike most of the net art works commissioned by Tate, both The Art of Sleep and The Art of Silence were hosted on Tate servers. In 2018, both works were acquired for the Tate collection and preservation options were explored as part of the acquisition process.34 Conservation strategies address the behaviours and characteristics that need to be preserved to maintain an authentic experience of an individual work. The selection of possible strategies to explore is therefore influenced by the characteristics of artworks, their functionality and the technologies of production along with the resources and expertise available in the institution or conservation team.

Understanding the artists’ approach to preservation is a key aspect of this process. YHCHI have transferred the majority of their work to video formats, which they host online via video platforms such as YouTube and Vimeo, and link to from their website. Video is, in general, a more sustainable medium than Flash, and makes the works accessible on mobile devices. The artists welcome technical improvements to their works: ‘The reason you want to make it better is because… these people are making the technology that we use. They’re always upgrading’.35

For both of the YHCHI works, the text and soundtrack are closely linked, and the way in which the text changes in rhythm with the sound is central to the work. This means that synchronisation must be exact. In this respect these works behave similarly to digital video, a view confirmed and reinforced by conversations with the artists.36 Using video, however, would change certain original properties of the work: the autoplay function, which allowed the work to start as soon as the window opened; and the lack of playback controls. When The Art of Sleep and The Art of Silence were first launched, these were considered important elements of the works, by both artists and their critical observers.37 However, the artists have since accepted the loss of these elements in their own restoration of their works.

With this in mind, and based on multiple conversations with the artists and the curatorial team at Tate, we explored several preservation approaches that would retain the original experience of the work. One of the first approaches we considered was emulation, or providing access to the original pages via an emulated browser. This means that a contemporary browser would display a historical browser with the capability to playback Flash. Emulation has proved effective in other time-based media conservation contexts, and research conducted by Rhizome has proven that it is applicable online and on a wider scale.38 However, on consulting Klaus Rechert, a researcher at the University of Freiburg and one of the leading experts on emulation, it became clear that the need for exact synchronisation of images and audio would be a challenge for current emulation technologies. As a result, this strategy was not pursued any further.

The second option we considered was to redesign the Flash animation using HTML5, a widely used markup language used for structuring and presenting content on the web.39 The language was designed for interoperability and consistency, as well as flexibility of use, and these are usually good indicators of software sustainability.40 We worked with developer Rob Pentha to extract individual video frames and accompanying audio and programme them to playback in HTML5. In the initial attempt, the synchronisation was not precise enough. Further testing proved that exact synchronisation would be possible but very labour intensive.

The third option was the one already being used by the artists and consisted of migrating Flash files to video. Made up of simple moving images, sound and no interaction, The Art of Sleep and The Art of Silence work well as video. The artists have also used video formats to display their works in galleries in the past.41 Furthermore, in terms of sustainability, digital video is ubiquitous and standardised, which means it is a simple matter of transcoding a video file between two different formats. The function of transmitting moving images via the internet is also likely to continue, even if the platforms around it change, which means that transfer to video is likely to be a sustainable and accessible solution. The one loss is that video images are not vector-based, and so zooming in on a video will create pixelation, which would not happen on the Flash file.

Artworks often change in response to changes in technologies. These changes can be seen as important to the meaning of the work. Even if the artists feel these are acceptable and not essential, there is still a sense of loss and compromise. Our aim is to maintain both historical and new versions online, and to continue to try and find ways to maintain the playback of the Flash-based version. Another route to preserving knowledge of how the work has evolved is by providing the contextual information included in the description of the work.

Conclusion

The simple animated text and music creations of Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries circulated widely on email lists and ‘best of the web’ postings from the late 1990s; in 2001 they won a Webby Award, described by The New York Times as ‘the Oscars of the internet’.42 Their works were known in technology and media circles, even used as examples of clever web experiences in classes in departments of information studies, without necessarily being recognised or identified as ‘art with a capital A’. Those who encountered the works this way might be surprised to find them in the Tate collection, and on display at Tate Modern, in 2023.

The artists’ website has changed little since the 1990s, appearing as a simple list of black text on white background, with industry-standard blue underlined text for links. As artist Vuk Ćosić commented at the time: ‘If actual curating of online stuff can only be done online, it is done by everybody alive and it is called “links”. And if you are able to draw sufficient attention, as a quality broker of dialogue about quality ideas, you will get people visiting your curatorial site and the links you have put there’.43 There is no complex navigation or hidden meaning in the list of links curated by YHCHI; it clearly shows if the works were made for exhibition; which can be watched on the web; and indicates the variety of languages the artists use in their work, showing its international reach and inclusivity. This list is also, for all its aesthetic brevity, at times confusing. It shows how the artists also made ‘works’ in response to invitations to give artist talks, such as ‘EVERYTHING WE’RE SAYING IS STUPID AND WR0NG – S0 ST0P ASKING US T0 TALK AND ST0P LISTENING T0 US TALK (F0R JANE AND L0UISE WILS0N / NEWCASTLE UNIVERSITY)’.44

The two works YHCHI made for Tate – the commissioned work and the work made in response to the request for an interview with Jemima Rellie – illustrate their strategy of refusing to modify their presence, online or offline, in response to invitations issued from the art world. Their conception of their art as illustrated on their website mixes commissioned work with their own self-directed output and ‘non-art’ productions in which they have collaborated. For example, in the subsection ‘Meet the Artists’, there is an entry that reads, ‘WHAT IS AN ART C0LLECTIVE? (TATE M0DERN / THE TURNER PRIZE C0MMISSI0N)’, which might lead you to think that YHCHI had been nominated for the Turner Prize. In fact, they were invited to contribute to the twelve-minute video explainer ‘What is an art collective?’ created by the Tate Digital team to accompany the 2022 Turner Prize exhibition, which featured several collectives, but not YHCI.45

Given the artists’ fluid approach to the categories and presentation of ‘art’, it should come as no surprise that the work(s) commissioned by Tate now exist in different forms: as digital video streamed online, as gallery installations, as a Turkish-language version and an ‘INSOMNIAC VERSION’, and are included in museum collections.46 We can expect they may yet change again, existing side-by-side and multiplying across the web and the world.