agoraXchange is a website and discussion forum created by artist Natalie Bookchin and political scientist Jacqueline Stevens that was online between 2004 and 2020.1 Through the collective design of a multiplayer online game, in which participants were invited to, ‘make the game, change the world’, the artwork imagined an alternative society. The website acts as an environment, or ‘agora’, within which people can debate what might be possible in the game and, by extension, in the world we experience outside it. For Stevens and Bookchin, the work presents a contemporary alternative to Thomas More’s Utopia (1516), a fictional satire about an island and the social, religious and political customs of its inhabitants.2

Fig.1

Screenshot of Natalie Bookchin and Jacqueline Stevens’s agoraXchange, phase 1, via the Wayback Machine, capture taken 10 February 2020, https://web.archive.org/web/20200210052812/http:/www.agoraXchange.org/index.php?page=218

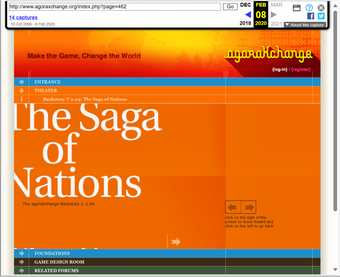

Fig.2

Screenshot of the top-level menu on the main page of the site

agoraXchange was initially accessed via Tate’s Net Art pages, which were superseded by Tate’s Intermedia Art pages in 2011. The website is no longer functioning, but there is an archived version that can be accessed via the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine (fig.1). The site comprises a homepage with a menu divided into seven top-level sections: Entrance, Theatre, Foundations, Game Design Room, Related Forums, Credits and Links (fig.2). Each section of the menu can break down further into separate subsections. The ‘Entrance’ section acts as the landing page for the site, with the ‘News’ subsection serving to situate new visitors to the site and provide a short explanatory text about the project and its current status. This includes an embedded news feed of real-world events related to the project, site updates and other relevant content chosen by the artists.

The other subsections under ‘Entrance’ are ‘Manifesto’, ‘Decrees’, ‘FAQ’ and ‘Timeline’. Under ‘Decrees’, Stevens defines the four political tenets for the game. Each in some way challenges what she describes as the existing ‘unnatural political institutions’ of society.3 Citizenship would be by choice and not by birth; wealth would be redistributed at death; there would be no ‘state jurisdiction over kinship relations’, such as marriage; and there would be no private land ownership, but instead lifelong leases for land would be given to individuals or organisations where the use of land was ‘non-harmful’.4 With these decrees as a basis, visitors could propose and discuss ideas for the design of a new game in which a new world could be virtually experienced.

Fig.3

Screenshot of the first page of ‘The Saga of Nations’ slideshow in the ‘Theatre’ section of the agoraXchange website; Wayback Machine, capture taken 8 February 2020, https://web.archive.org/web/20200208103943/http://www.agoraxchange.org/index.php?page=462

The ‘Theatre’ section uses an image-based click-through slideshow, called ‘The Saga of Nations’, to communicate the backstory used as the foundation for the game design activities (fig.3). The text describes the effects of birthright on social structures and ‘how nations came to their demise’. The images accompanying Bookchin’s text – media photographs of the attack on the World Trade Center in 2001, of Guantanamo Bay detention camp and of the torture of Iraqi citizens by American soldiers – locate the artwork at a particular moment in time, three years after 9/11. The ‘Foundations’ section includes texts discussing the theory behind the project.

Most of the user interaction took place in the forums and in the ‘Game Design Room’, through a basic commenting and voting system. It functioned as ‘a collaborative workspace where participants would discuss, debate, and develop the game design’.5 The next section, ‘Related Forums’, contained other user forums not directly related to the game design process but focused on relevant topics, such as political theory. Discussions in the forums concerned with game design often turned into discussions about potential societal change. Bookchin had hoped this would happen; she writes in a post on the website that she wanted the ‘“messiness” of human relations to come through in the game’.6 The ‘Credits’ section contains information on the design and funding for the project. Finally, the ‘Links’ section of the site is organised by subject, including ‘Games and Online Worlds’, ‘Border and Immigration Net Activism’ and ‘World and Law Resources’.

Making and commissioning

agoraXchange was conceived as a platform for exchange and discussion. Bookchin explains how they approached the design: ‘We were thinking about it as architecture – how do you produce certain movements and interactions within a space that can feel productive?’7 The work was created a year before Facebook launched, when there were few online environments for virtual social interaction and discussion. With this in mind, Bookchin and Stevens wanted to create ‘an alluring, utopian space that you would want to be a part of’.8

The collaboration began in 1999, through a conversation between Bookchin and Stevens on the ‘efficiency of the politics of parody’.9 At that time, Bookchin was working with RTMark (®™ark), an activist collective known for pranking and parodying American corporations.10 Jacqueline was familiar with the collective and wanted to explore how fiction and parody might be used as a political gesture. Working together, Bookchin and Stevens presented an idea for a multiplayer artwork at the symposium user_mode = emotion + intuition in art + design at Tate Modern, London, in 2003.11 The following year, Bookchin was approached by Jemima Rellie, Head of Digital Programmes at Tate (2000–07), and proposed agoraXchange in collaboration with Stevens.

There are two phases and two websites for agoraXchange. The first, described above, was created by Bookchin and Stevens and could be accessed until 2020 on www.agoraXchange.org. The second phase, which was not part of the Tate commission, was launched in 2008 and could be accessed on agoraXchange.net. Both are now accessible via the Wayback Machine.12 The second phase was led by Stevens in collaboration with media scholar Ayhan Aytes, artists Zeljko Blace and Ana Carvalho, web designer Colin Sagan and the socially engaged design collective quilted.org. This phase differed from the first in that it allowed people to vote on the choices that had been made in the previous iteration of the artwork.

Reception and interpretation

agoraXchange has been described as an example of activist gaming in net art, as ‘tactical media’ and as an example of a massively multiplayer online role-playing game (MMORPG).13 In her book Tactical Media, Rita Raley considers agoraXchange an example of ‘persuasive gaming’, part of a movement in media practices that engaged and critiqued the dominant political and economic order.14 She describes how the website, like other examples of persuasive gaming where political arguments are made by game mechanics, ‘advocates for social change’. It differs from other examples in that ‘it does not run the kind of gaming scenarios possible in sims-type environments’ and enables comment, debate and analysis rather than action.15 New media scholars Joline Blais and Jon Ippolito meanwhile connect the statement at the heart of agoraXchange – ‘make the game, change the world’ – to Buckminster Fuller’s World Game, developed in 1961 as an educational simulation tool for addressing overpopulation and redistribution of global resources.16

Media scholars Nick Dyer-Witheford and Greig de Peuter highlight the work’s potential for collective gaming, describing it as ‘a virtual world influenced by the wave of writing about “life after capitalism” that accompanied the turn-of-the-millennium counter globalization movement’.17 In a review of agoraXchange, artist and co-director of Furtherfield, Ruth Catlow, similarly situated the work as an example of a zeitgeist for net art activist gaming. She criticises how the work creates barriers to openness and inclusion through its use of language:

This art project, which also aims to liberate our creative imaginations, would be more successful with a shift of emphasis towards visual language, as a more generative, multilingual and accessible form of communication than the culturally encoded and politically loaded (in the global sense) use of (English) text.18

Stevens provides further context for agoraXchange in States Without Nations: Citizenship for Mortals (2009), which was developed in conjunction with the website, with one informing the other.19 The book explores the ‘alternatives to our current laws that base citizenship on parochial, unjust ideas about birth, and shows how these laws are connected to other archaic practices inconsistent with liberalism, including inheritance and marriage’.20

The artists’ practice

Natalie Bookchin’s work is concerned with the construction of meaning, reality and knowledge. She often engages with politics ‘relating to the intersection of the body and gender and technology’.21 She has explored these ideas through gaming, sensing that in games players take a position and an active role in the story rather than simply identifying with an image.22 Bookchin began making work online in 1997 following her series of interactive CD-ROM artworks, including Databank of the Everyday 1996, which brings together a computer database with a stock photography catalogue.23 Her move towards working online was also informed by her experiences of teaching. In the late 1990s, while teaching a class called ‘Introduction to Computing in the Arts’, Bookchin found that she, ‘didn’t know very much about computing in the arts’, and as a solution set some homework for her class (and herself) to create websites.24 This class exercise was later found by net artist Heath Bunting who, appreciating the idea, shared it online. As artists began making websites and sending their ‘homework’ to Bookchin, the visibility of her work grew. At around the same time, Bookchin worked with the artist Alexei Shulgin to write a parody account of net.art.25

Through these actions and experiences, as well as through her involvement with RTMark, Bookchin began thinking about the internet ‘not just as this new platform for distribution but as a site in itself that can be considered a space where artists and activists could develop ideas and work’.26 Today, Bookchin acknowledges that while the internet remains the principal subject of her work, at a certain point in her career ‘the internet as a site no longer seemed viable’.27 She has reflected on that change, asserting that ‘there is no internet. Even the idea of saying that there is an internet and there is an online space and an offline space no longer makes any sense. It used to’.28

Jacqueline Stevens is a scholar of political theory who has written about constructions of citizenship, the nation state and the law. agoraXchange was her first collaboration with an artist. Stevens has described how her work as a theorist was directly impacted by her experience working on the commission, from creating the website, to working with programmers and promoting the site with Bookchin through talks and festivals:

The engagement and the opportunity to network with digital artists all over the world really changed the nature of my own work in academia. I moved from being somebody who just worked on textual exegesis to very actively engaging legal reform and working with a broad community of lawyers and journalists.29

For Stevens, the collaboration with Bookchin began as a way of encouraging people to engage in politics. The second phase of the website in particular was aimed at developing engagement, with more opportunities to participate in decisions through voting. She also began to translate ideas from agoraXchange into the design of legal frameworks. This had a direct impact on her practice of law and has informed her work on citizenship and deportation practices in North America. From working on agoraXchange, Stevens learnt the ‘the ability to not just come up with the idea but to think about ways of using the internet to reach out to people’.30

Technical narrative

The agoraXchange project created an online environment where a community of users could collaborate on the rules of a game. Because of this participatory element, the boundaries of the work could be thought of as extending further than the website alone. The website however, now only accessible through the Wayback Machine, is a unique record of those interactions between participants, in the same way that video documentation may be an acceptable replacement for a live event.

Of the two phases of the agoraXchange project, we are focusing on the first, which was commissioned by Tate in 2004 using the domain agoraXchange.net.31 At this time the authors also acquired the domain agoraXchange.org, which until 2008 redirected visitors to the .net page.32 Phase I was active from 2004 to 2008, meaning that the content of the site was continually added to and amended. Additional subsections were added over time.33 For example, a section titled ‘2006: Next Step, Phase I.1’ was added on 26 January 2006 , where users were invited to help process discussions into sets of Yes/No questions to facilitate voting on various features of the game in development.34 In 2008 Jacqueline Stevens started phase II of the project, moving the phase I site to AgoraXchange.org.35 Tate’s Intermedia Art pages were not updated in that year to reflect the change in URL, so from 2008 to 2020 the link would lead visitors to phase II of the project rather than phase I.

Looking beyond domain names, it is also interesting to look at how and where a website is hosted – that is, where the digital files that compose a website are stored and managed. There are two main options for this: an artist may decide to host on their own server, giving them complete control and responsibility for building and maintaining it, or they may opt to have the website hosted by a hosting platform. Hosting platforms provide and maintain the storage and technical infrastructure needed to keep a website online. This usually has a cost, which may be dependent on the computing resources used by a website or the number of visitors it receives. In 2019, when analysing the then live agoraXchange.org, under the entrance submenu ‘document for translation’, we found a reference to www.kein.org, an artist-run networking initiative that provided free hosting for artistic and activist projects. Looking at captures from the Wayback Machine, we can see that kein.org supported and linked to agoraXchange.org between 2005 and 2007.36 The project is not listed after July 2007 and the kein.org website seems to have been taken down in 2015, although they are still supporting projects.

Fig.4

One of the banner images from the phase I site

Fig.5

Screenshot of the scrollbar used on the phase I site

Technically, agoraXchange is representative of the period in which it was made. The artists worked with artist Cynthia Madansky to design the layout and navigation of the phase I site. The New York-based agency FDTdesign provided the visual design elements, user interface and programming, including the backend administration interface. The banner images displayed at the top of each page are 711 pixels wide site, indicating that the site was most likely designed for browsing on 4:3 computer monitors at a resolution of 800 by 600 pixels, a widely used format when the site was produced (fig.4).

The site makes use of interaction elements defined in the HTML and client-side JavaScript.37 This approach – creating elements such as scroll bars from HTML, CSS, JavaScript and graphical assets (fig.5) – is typical of the period. In this case the code seems to have been borrowed from a developer who added this note to the JavaScript:

// Made by geeeet@ghtml.com

// Keep these two lines and you're free to use this code

This was a common way of working at the time, with developers sharing code on their webpages.38 This use of JavaScript and HTML was sometimes referred to as ‘dynamic html’ (DHTML) as it allowed for dynamic interaction and feedback from web page elements.39

The simple commenting and voting functionality of the site’s forums is provided using PmWiki, an open source wiki-based content management system written in PHP (initially referring to Personal Home Page and now to Hypertext PreProcessor).40 At the time, there were various solutions for creating and hosting online forums, including open source content management systems such as Drupal, which was used to implement a forum on the phase II site.41 PHP enables the pages of the site to be dynamically updated to incorporate user comments. PHP is widely used on the web to fulfil this type of functionality and can dynamically produce HTML based on user input that is then processed and delivered back to the browser to render.

Current condition

All pages of agoraXchange are now offline, and the URLs agoraxchange.org and agoraxchange.net lead to pages with a short message explaining that the site is no longer functioning.42 There are recordings of both agoraXchange sites on the Wayback Machine, from as early as 2003, but the forum features were not captured, so the discussions are missing from the record.

In this section we will identify the risks for preservation of agoraXchange and the strategies used to mitigate those risks. We have identified the participatory element of the website as a central function of the artwork. The website itself is valuable, therefore, as a document of the interactions that took place in it. It is essential in understanding how discussions were framed and the technological environment in which they took place.

The first consideration in preserving the website is hosting, and how engaged site owners are in maintaining the site online. During the commissioning process, it was decided that the site would be hosted by the artists. Jacqueline Stephens kept the sites for both phases of the project online from 2004 to 2020. It was agreed that Tate would have no control over these pages, so that if the artists decided to stop hosting the websites, they would go offline.

There are multiple recordings of both websites via the Wayback Machine, but the forum discussions have not been captured. While the site was online it may have been possible to extract the forum conversations using a tool such as GNU Wget, or create a web record using Conifer.43 If agoraXchange were to come into the collection, Tate would aim to obtain a complete copy of the site in its most recent form, which could be set up on one of Tate’s servers. An agreement could be made with the artists about the conditions of access to Tate’s version, given that the site is now unavailable. Tate would need to ensure the longevity of the artwork’s domain names, as these must be continuously paid for at the risk of being sold and used for other purposes. Given its particular nature, the conservation strategy for this work would need to include a decision on if and under what conditions the project would restart forum discussions. The alternative approach would be to present that part of the project as a fixed archival form, without reactivating the website forums.

In her interview, Bookchin recognised the importance of archiving and historicising net art, while questioning the way that this responsibility often falls to the artist: ‘I think there is a lot of value in saving and archiving this material. I think it’s really important to understand it and know about it today, but I also don’t want to be my own historian’.44 The invisibility of net art, like other forms of occlusion, is a political issue. If a story is told and some part of it is not included then it can become forgotten, ‘so if it’s not archived or it’s not represented then it doesn’t exist’.45 The challenge is how we situate an artwork like agoraXchange in art and politics and as a form of public art.

There is an interesting question that arises when preserving a work like agoraXchange, which records interaction at a particular moment in time – namely how the artists collaborating on the piece have different relationships to its ongoing iterations and how that is managed. For Bookchin, the work is complete: ‘agoraXchange, I think that that page is done. That’s archived’.46 For Stevens, agoraXchange has remained more active, partly because she developed the second phase in 2008. But the site has also acted, for Stevens, as a pedagogical tool. For example, Stevens used the forums on agoraXchange as a space for posting and discussion for her students in a ‘Social Theory and the Law’ course.

There could also be shifts in how we encounter the work. At the time of the commission, Bookchin considered agoraXchange as an artwork to be experienced sitting at a computer. But more recently she has addressed how the work might be encountered in a gallery:

If it were in a space, it might be printing out some of that stuff. People might interact with the website very differently than they would have in 2004. I certainly could see it that way. It’s not that a lot of new material would have to be generated, it’s really more about pulling some of that out. Also just understanding it.47

Conclusion

Bookchin and Steven’s work on agoraXchange reached beyond the net art scene, not only as a work of art but also as an experimental public stage in a research project and as a tool for teaching. Like many of the other net art works commissioned by Tate, it serves to interrogate what net art is, the forms it can take, and the uses to which it can be put. The Tate commissions undertaken before agoraXchange included immersive meditative experiences – such as those created by Simon Patterson and Shilpa Gupta – and critical engagements with organisational structures, such as the works by Graham Harwood and Susan Collins.48 agoraXchange falls into what is now more commonly understood as ‘world building’. It builds upon the model of multi-player environments (or MUDs, short for multi-user dimension, domain or dungeon) created using text chat and invites users to chat forums to play with the rules in building this new world. As such, the work marked an important development for Tate in commissioning works of net art that acted within and informed actions in the real world, rather than solely for viewing or experiencing art within the browser.

The press release from Tate explained that the public would participate in the world building via the site’s forum, after which ‘a committee of artists, activists, and political theorists will be convened to review the submissions and conversations for the purpose of proposing the possible games’.49 This approach tapped into a cultural phenomenon of empowering participants in the creation of content, and the increasingly blurred boundaries between individual online experience, networked gaming and stream-on-demand broadcast platforms. Driven by financial incentives to turn web users into consumers, in 2004 platforms began to prioritise centralisation, as evidenced in the launch of Facebook a month earlier. Sitting squarely at the midpoint of Tate’s net art commissioning programme, and with its focus on user participation, agoraXchange marks a turning point. It represents a form of net art that exists within the wider category of socially and politically engaged, public or participatory art, but which just happens to use online space to do so. A few weeks after the launch of agoraXchange, an article in The New York Times questioned whether net art’s boom had, in fact, bust.50 As such, the invitation to imagine a new post-capitalist society, in which non-extractionist, non-harmful rules of engagement determine social interaction, had come just in time. With the rise of the metaverse, such experiments in collaborative world building are more relevant than ever.