This paper outlines the philosophy and approach that Tate Learning has established in order to inspire and invite the widest range of participants, with the aim of sharing and shaping the profound opportunities that arts’ learning affords. We believe that art is a powerful catalyst for creativity, critical thinking, emotional reflection and social connectivity. It is vital to the growth of our children and is core to innovation and the creative economy.

Inspiring learning – current context

There are four different galleries that form the family of Tate: Tate Modern, Tate Britain, Tate Liverpool and Tate St Ives. Approximately seven million people visit the galleries each year. Currently we have sixty members of staff across all four sites who provide learning programmes for approximately one in eight of our visitors in – gallery, as well as at least one million further learners online. Our teams include experts in early years and families, schools and teachers, young people’s programmes, digital learning, interpretation and public (adult oriented) programmes. In 2013 we ran nearly 2,000 separate events and activities. We offer these activities seven days a week for the public and apply a ‘one third’ rule in our programme: one third of all our work in Learning each year focuses on the collection, a third on exhibitions and a third on broader arts –learning agendas and emerging ideas in the public realm. In this way we try to work closely with the curatorial programme whilst also remaining sufficiently fleet of foot in being able to respond to social and cultural changes and developments as they arise.

Our aim is to maximise learning experiences with art, both within the gallery and beyond its walls. We want to make the most of the public’s encounter with art by creating meaning through its aesthetic qualities as well as from the many ideas that artworks provoke in the viewer. To this end, our role is to support the public’s learning, not to assume that everyone can access art and ideas easily, but to provide contexts and the conditions for learning that inspire people to look and think deeply; from the novice to the expert there is always something more to enjoy and to understand. It is our responsibility to engage a wide public who wish do so.

Our approach to learning with art

The values that Tate Learning is built on are shaped by Tate’s overarching vision and include a democratic, public-focused approach to our work. We are committed to inclusive and equitable practices that involve participation and the co-construction of experiences and knowledge with the learners. We have respect, openness, risk and curiosity at the heart of what we do and as the central values to which we always return. Our ambition is to create new forms and environments for learning that push forward our practice and make a difference to arts-learning more broadly, increasing the perception and participation in visual arts for the public. In this we seek to address the following:

- How to make clear our values and intent.

- How best to go about developing programme.

- How to articulate our practice and the value for participants.

- How to create new spaces for new programmes.

- How to do all of this with research and evaluation at its core.

The detail

Learning is the term that describes profound human processes of change; this includes, (but is not limited to) cognitive, social and behavioural change. Learning is the personal journey that takes us from what we thought yesterday to what we understand today; learning with art, which so often asks “what if?”, invites us to imagine how we might see and think differently tomorrow. Indeed arts – learning is unique as a discipline in that it explores how abstract ideas are made manifest through aesthetic qualities, it deliberately engages with emotions and generates meaning through complex human intellectual and social interactions. It is therefore contingent, ever changing and wrapped in the complexity of human subjectivity and the imagination. Yet in today’s world, the high value given to knowledge as something concrete and fixed, dominates many educational practices. Perhaps this is even more evident in our current time of global change and uncertainty in which there seems less and less space for ‘contingent’ thinking to happen in educational (or even professional) settings. This is at odds with the necessity for us to do so, to be able to adapt to our changing world, a world in which learning with art is so powerful because it does navigate the uncertain, it relies on the subjective, it demands the critical and interpretive and invites imagination, flexibility of thinking and the capacity to assess and evaluate, make decisions and judgements as well as communicate in the social realm; it embodies the very essence of the kind of tolerance and divergent learning that we and our children will need to flourish in the world of tomorrow, if not today.

Put simply, our approach in Tate Learning is to ensure that visitors are able to access sufficient skills in ‘learning how to learn’ to build their own knowledge with art. The aim is for the public to recognise when and how they are gaining knowledge so that this is replicable beyond the moment; this means that the experience of learning needs to be visible and explicit to people taking part, unlike many educational experiences that veil the processes of learning or indeed assume that learning is taking place merely because activity is happening or information is being given. Not everyone, and indeed less than one might suppose, feel confident enough to look at, enjoy and make meaning with art. Its not that people can’t or don’t have the capacity to do so, it’s that we separate art from the every – day, we actively create barriers physically, socially, emotionally and intellectually from very early on and in doing so make hard work of an engagement that is essentially about looking, feeling, thinking and creating; four fundamental human traits.

To this end we have sought to design active learning environments where enquiry can happen, where the public take ownership of what they learn through a wide range of programmes that also invite participation and learning through reflective experience. This means that those involved quite literally ‘see for themselves’ or create for themselves, the contingent processes involved in working with ideas or activities in art. Our aim is not to withhold knowledge or information, we are not inviting opinion over (or instead of) knowledge, it’s that we try to find appropriate ways of making clear the perspective generated by the knowledge available and offer opportunity for this to be challenged, rethought or reassembled. This has led to programme design in collaboration with artists, educationalists, scientists, philosophers, etc., as well as participants, to explore the broadest range of perspectives and to figure out the many and different ways that they can be imagined together; a creative act in which people make their own difference. Setting up such programmes is harder than one might imagine and is resisted sometimes when people feel a need to be told ‘how it is’; this is unsurprising, given that this is how we have been taught, and what is modelled in many formal education systems. However, the aim here is not to create situations where we transmit our own knowledge by stealth or give one form of knowledge priority over another and that over the experience of learning itself, it’s about giving up the idea of the authority of knowledge to the value of learning.

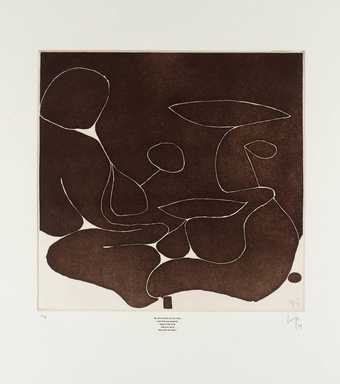

Victor Pasmore

‘By what means can we know?’ (1974)

Tate

Reflective Practice – Our approach to programming

Over the last ten to fifteen years, there has been a growing change in both the theoretical debates and the daily activity for institutions. This includes (but again, is not limited to):

- A sense of movement from passive reception to a more participative public involvement.

- A shift from a standardized ‘one-size –fits-all’ approach to one that was personalised.

- A reduction in transmission models for learning to co-constructed dialogical models.

- A change in perspective about knowledge that although contested has moved from what you know to how you use what you know.

- A change from the single authorial voice of an institution to a sense of plurality and many voices within and outwith that contributes to the whole.

- A shift from the institution as a private knowledge holder/receptacle of knowledge moving towards being an open resource for public access and understanding.

These shifts can generally be said to match our own changing approaches to learning with art. They have generated a need to rethink how we go about the learning processes involved in our own professional practice in order to co-construct the kinds of learning environments we imagine with participants. This re-think has resulted in an approach for Tate Learning based in reflective practice, which has become known as Transforming Tate Learning. We began Transforming Tate Learning in 2011 and worked with Steve Seidel (Patricia Bauman and John Landrum Bryant Lecturer on Arts In Education, Director, Arts In Education programme, Harvard University) to establish five stages of work that would underpin our changing professional practice. These are:

1. Identifying our core values and the necessary conditions for learning that emerge from this.

2. Identifying how these values are made manifest in our programmes

3. Identifying the processes and mechanisms that need to be in place to enable us to understand what is happening and to account for the experience of those participating.

4. Drawing together and analysing our findings in order to develop broader understandings and build theory.

5. Ensuring that what we find through the process feeds back into practice and is disseminated appropriately.

These five stages included the participation of all our teams across sites and involved a series of on-going discussions, workshops, cross-site research seminars, debates, clarifications, definitions and the creation of new approaches and programmes, collaborations with externals and many tough questions. We worked with Eileen Carnell (formerly a Lecturer at the Institute of Education, London) to support and keep the momentum going for the team. Transforming Tate Learning is an iterative process and one that we all continue to work on so that we are able to account for our values, embed rigour and reflexivity into our work, identify what it is that we are evaluating and enable us to ask better questions at the right time. The process helps us to select appropriate data collection methods for research and evaluation and ensures that we share what we are finding with others. In many ways it functions as an action research programme for the entire team.

It has had a profound and positive impact on Tate’s learning practice and has made our work more visible within the institution, better articulated and with clear aims aligned to our deeply held values. It has changed our thinking and the work that we do. We are still in this process, beginning to form better ways of finding out the impact of our work and forming theoretical frames as to why and how different kinds of programmes result in different benefits/outcomes for the learners (including ourselves).

One of these frames looks at how we use time, space, content and pedagogic methods to see what’s happening in our work. We are exploring how these four aspects, all of which can be changed, match the context of the work. It raises some interesting questions: How can we best configure a way of putting together these four key elements that result in the most rewarding learning for our participants? What happens if one of these aspects goes wrong? How do we construct experiences that maximise the conditions for learning using such a frame? Are all aspects equal in value, and are there recurring qualities of these four elements that we can identify in order to repeat successful outcomes?

We are currently exploring these questions and this gives just one example of the ways in which we are challenging ourselves to take experience and case-studies to a level in which we can hypothesise on the value of our work and ask what learning takes place for individuals and why, so that we may understand the bigger picture of what’s happening when we learn with art, and improve on what we do with our public. It seems that memorable, out of the classroom content-rich work that explores art and ideas has many yields. These include, but are not limited to: new forms of co-operative social interaction amongst the participants and across ages, a more developed language that uses metaphor and simile and that flexes the imaginative muscle (important for creativity and innovation), a growing ability to analyse and synthesise and in doing so the capacity to make informed judgements and form opinion. More open-ended programmes encourage divergent thinking and speculation (applying knowledge across contents and artworks), self-led and peer-led programmes invite and achieve personal and emotional enrichment resulting in confidence for participants as well as a raft of new skills and capabilities. We now aim to leave our programmes open enough that they will inspire curiosity and afford an ownership of learning and independent thinking by those taking part. We try to create conditions and spaces that are surprising as well as reflective, exploring how ideas are made manifest in artworks and how we may embrace contingency and inspire a passion to learn.

Where next?

Our current challenge is to invite more people into the conversation about art and into co-constructing learning activity at Tate. To this end we seek to diversify learning experiences with art; that is to say that we need to change the types of programme, the spaces and the approaches to programming that we make in order to help diversify our public (space). We wish to extend learning experiences with art, which means that we want to explore how we can grow our reach and enable more people to have access to learning with Tate in and out of the gallery, such as creating resources, more developed interpretation and digital learning opportunities (time); and lastly, we wish to deepen learning experiences with art which means that we want to develop research, training, national and international networks and a more sustained engagement for the public within and beyond the gallery before, during and after a visit (method); all of which we wish to do in order to expand access and engagement with art and Tate’s collection (content).

To achieve this we are working on a new programme with colleagues across the organisation, as well as with partner organisations, artists and individuals in order to create a place for exchange. The ambition is to generate hands-on public engagement, interaction and participation at a much greater scale, depth and reach than we can presently achieve. Audiences will be invited to learn and contribute through an exchange of knowledge and ideas, help shape outcomes, and thereby contribute to cultural and civic life.

The purpose of creating a place of exchange is to take the next step on our journey in learning and to embrace the challenges of our changing world. We wish to explore a new model for the ‘new museum’ and strengthen the visual arts infrastructure in service to the wider sector by exploring new ways of working. This is an invitation for everyone to join the conversation and to learn – for oneself, from others and with art.