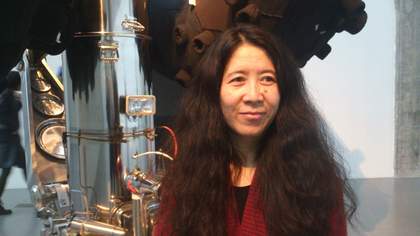

Yin Xiuzhen at Pace Gallery, 2013

Photo: Monica Merlin

Monica Merlin: Could you talk about how the situation for women artists has changed in China since the 1990s?

Yin Xiuzhen: I will focus on the situation in contemporary art. At my university there were two classes: oil painting, which I studied, and traditional Chinese painting. There were twenty-five students in my year, of which four were female. It was the same in the year above – four female students. I found it strange. I wondered if it was because of the entrance exam, but the exam was open to anyone, male or female. In any case, there were very few female students in my year, and after separating them into two classes, there were only two left in my class. Later I found out that there were more female students at the Central Academy of Fine Arts, but I went to Capital Normal University, a school that trains teachers. They have more female students now, but still only six or seven, never more than fifty per cent of a class. Female students are always a minority, and even fewer female students become artists after graduation.

This disparity is connected to our education tradition. For a woman, higher education is the ultimate goal. After women have received their education, they are expected to return home to look after their children and family. This is why many women artists stop practicing after graduation. In the early days of contemporary art exhibitions, there were very few female artists. I remember at a seminar during a Chinese contemporary art exhibition in Bonn, someone asked why there were no women artists. The curator said ‘because there are not any women artists in China’. This made people angry. The Women’s Museum in Bonn said they had to hold an exhibition of Chinese women artists, so they sent a Chinese woman artist based in Germany to visit China to search for women artists. That was how they found me. I heard the story and it made me laugh. They then curated the exhibition Half of the Sky: Contemporary Chinese Women Artists in 2011.

Gradually, people started thinking about the question: why are there so few women artists in China? Why do we not see women artists in exhibitions? When male curators considered this issue, they would say, ‘It is not right that my exhibition has no female artists. Let’s find one.’ It felt like when you add seasoning to your cooking – ‘Let’s add some salt.’ They would find one or two women artists just for the sake of it. They certainly did not appreciate art by women artists; typical praise for a woman artist would be something along the lines of, ‘Her art does not look like a woman’s work. It is very powerful.’ This shows that they believed women were only good at petty details and their work was only ‘powerful’ when it looked like a man did it. While it might be true that men and women have mental and physical dispositions, which means they may be interested in different subject matter, there are of course overlapping areas of interest. In fact, some male artists can create very detailed work, or adopt other typically ‘feminine’ tropes in their work. This is quite normal.

I do think nowadays we have lots of women artists – many more than in my day. I do not know all those young artists very well, but I know that many of them are doing quite well out there and they are good. They have plenty of opportunities and venues to exhibit their work. Back in the 1990s, it was all underground. There were no exhibition spaces and we often found a place in the suburbs and simply left our works there. Or we did exhibitions at home and invited people to come.

Monica Merlin: Have you encountered any difficulties when exhibiting your work? Do you think these difficulties of exhibiting might have related to the artists’ gender?

Yin Xiuzhen: If they did not invite me to exhibitions because I was a woman, I had no way of finding out. But I did get invited to some exhibitions just because they needed a woman artist. Some people said to me that my works did not look like they were made by a woman, for example, Washing the River and The Ruined City, both of which used cement powder and tiles. I have also produced works that might be more stereotypically ‘female’, for example, using a needle and thread as materials. But for those works I was just following my heart. I chose needle and thread based on the piece I wanted to make, not just because I am a woman.

Yin Xiuzhen

Ruined City 1996

Installation, with furniture, cement powder and tiles

© Yin Xiuzhen, courtesy of Pace Beijing

Monica Merlin: They must have been surprised when they found out that you, the artist, was a woman. How did you feel about that?

Yin Xiuzhen: I did not feel comfortable. They were looking at women artists through tinted glasses. In their stagnant thinking, they believed women and men should each behave in certain ways.

Monica Merlin: In the 1990s you used a lot of cement, which might have seemed macho to a lot of people. Do you think they judged you for the material you used?

Yin Xiuzhen: They did view my work in terms of its materials, but I only chose cement because of its special character. At the time, China was undergoing rapid changes. Demolition was happening everywhere and you could smell cement in the air wherever you went. After getting married, I lived in a single-storey house; a hutong. I saw many other single-storey houses disappear one after another. They were a type of Chinese traditional architecture and it was extremely painful to see them go. I chose cement also because I like how its soft and powder-like form turns heavy once mixed with water. These are the reasons I chose cement; I was not trying to be like a man by choosing something dusty and tough.

Monica Merlin: Looking at your works from that period, I see a paradox between the texture and the weight of the materials you chose. For instance, cement can be soft as well as heavy.

Yin Xiuzhen: I have liked this kind of contrast since my earliest work, Dress Box, which I made in 1995. I sewed together my clothes from childhood to adulthood, stacked them in a trunk, and sealed them with concrete; the concrete was hard, but the clothes were soft. The concrete looked cold, but the clothes felt warm and carried my warm memories. This is how I feel about our society: everyone has a soft side in their heart, but they have to toughen up when facing society. This kind of contrast is everywhere, and it has become an ongoing element in my work.

Monica Merlin: Some reviews said that your art displays feminine characteristics. Do you agree that your work is feminine? What you do think of femininity in art?

Yin Xiuzhen: Actually, I have never considered this, but many people have asked me about it. Since the beginning of my career, I have only made art because I find something interesting or because an idea strikes me. When I look at other artists’ works, I do not see them in terms of male and female. Whether I like it or not depends on how I feel about the work itself. You [to Merlin] are researching women artists, so you study and analyse the relations between male and female artists but, for me, this never crosses my mind.

Monica Merlin: I think no individual is completely independent of the context that they live in – their country, history, society, family or other circumstances. I am interested in an artist’s personal experiences. When you started making art in the 1990s, your works were related to the house, the area and the city that you lived in. I agree that your art is not necessarily related to gender but, in my opinion, when a person is growing up, their society and family have different kinds of requirements and expectations of them, depending on whether they are a man or if they are a woman. This surely contributes to what kind of person one grows into. I wonder if you have thought about the type of pressure you have experienced as a woman – the pressure from your family, as well as the rapid development of Beijing and society at large.

Yin Xiuzhen: I think the situation is different between urban and rural areas. My mother is from a rural area but later moved to Beijing. I noticed the difference between men and women when I went to her hometown. Women do all the cooking and men take all the prime seats at the dinner table. Boys get better food than girls and more of it. I could not understand it, because at home, in Beijing, my mother treated us equally. I could not see any difference.

When the Tangshan earthquake struck in 1976 with a magnitude over seven on the Richter Scale, my aunt – my mother’s younger sister – picked up one of her children before rushing out of the house. On her way out, she realised that it was her daughter in her arm, not her son. She then put her down and went back to take her son. Her daughter hated her for it, and their relationship was not very good afterwards. The daughter knew that her mother treated her differently from her younger brother.

There is a reason why people in rural areas tend to prioritise boys over girls: when parents get old, they usually live with their son, because once the daughter is married off, she is out of their hands. If they have two sons, they will live with one son for a year, and then with the other the next year. They will no longer have a house of their own, because they would have given it to their children. The situation is still the same now in rural areas but you do not see this so much in urban areas.

However, my father and mother did have different expectations of me. My father thinks that a girl does not need to achieve too much. I did science in high school and when I failed the university entrance exams my father asked me to get a job. But I was not willing to and insisted on trying again for university. I did science, which was mainly about maths and physics, but I was actually interested in fine arts. To enrol as an art major, I had to pick up new subjects like history and geography, so it was a hard time for me. I got a temporary job and worked every day because I did not want to ask my family for money. In the evening, I went to classes in preparation for the exams. And on the weekend I studied painting. That was how my career as an artist began.

My mother, on the other hand, was always very supportive of me. She said I could keep taking the exams until I did not want to do it anymore. But my father told me to ‘just get a job and make some money’. He thought that a girl should not work so hard. My mother is someone who is strong and eager to excel, like the legendary heroine Mu Guiying. She believes that girls should succeed in every aspect and be independent. I inherited that from her.

Yin Xiuzhen

Nowhere to Land 2012

Installation with used clothes, steel, stainless steel, mirrors, headlights

330 × 240 × 210 cm

© Yin Xiuzhen, courtesy of Pace Beijing

Monica Merlin: Can you talk about the title and background of the works in your current exhibition, Nowhere to Land, at Pace Gallery?

Yin Xiuzhen: The background is our contemporary life. My art has a lot to do with society. No one is separate from the society in which they live. No matter what ideas you have, you have to live on Earth and, for us, in China. I live in Beijing, and every day I open my windows to look outside. This is a habit from my upbringing: my mother said you should open the windows for ventilation every day because the indoor air quality is not as good. But now, I must watch the weather forecast every day first. If the smog is severe, I will make sure that all the windows are shut. In the old days, we opened windows to get some good air from outside, but nowadays the air is much better inside than outside.

The air pollution in Beijing now causes quite a lot of pain, particularly for those who have children. It is easier for adults as most of them have a strong immune system, but small children are still in the process of growing. Air should not be a luxury, but it is now for us. I feel very happy every time I see a blue sky. No matter how busy I am I will spend some time outside to take some deep breaths. I will also tell my child that she can run a few more circles in her PE class. But when the air is not good, I will tell her not to go outside even if her teacher asks her to. I told her, if she is asked to go out to do some exercise on a bad day, just say, ‘my mother does not allow me to go out today’. Of course I worry that the teachers will not be happy, but my daughter’s health is much more important. When the air pollution index is high, it means that once you have inhaled the pollution, you will never be able to get it out. It can cause grave damage to our health. Pollution has been very bad this year – more than half of October had dangerous levels of pollution, and we rely on the wind to blow it away. It is sad.

Because my child is Chinese, I want her to receive a traditional Chinese education. My hope for her is to establish her cultural roots before she goes on to absorb things from overseas. I do not want to send her abroad just yet. I have struggled with that quite a lot – I wish she could enjoy clean air abroad. Many of her classmates have transferred to schools in Singapore, America and the UK. Sometimes they send her photos – ‘Look at our blue sky and green trees!’ – it makes us so envious here.

It is a practical issue that needs to be solved in China. What should we do? That is how I came up with the title Nowhere to Land. We are a developing country. London used to be the ‘city of fog’ and it experienced the same issues. We should be far-sighted and learn from the experiences of others. We can avoid the mistakes that other countries have already made. Pollution is also a global issue, since one country’s pollution can affect pollution in other countries. In China, sewage water is injected through pipes into the depths of the earth, which pollutes drinking water. More than half of the water sources in Beijing are highly polluted.

People cannot live without fresh air to breathe, or water to drink; these are the basic rights of every human being, but now they are under threat. This makes me feel very sad. It used to be the demolition of houses and relocation of people in Beijing that made me sad. Now it is this issue of breathing and basic survival. A lot of food scandals have also been reported lately. Often the media tells you what has been poisoned, what you should stop eating and how you can tell whether something is real or fake. But I believe that food specialists should inspect all food before putting it on sale. It should not be left to the consumer to test the food after having bought it; it should not be left to the consumer to report to the media if their food is fake or poisonous.

I made the piece Nowhere to Land in such an anxious state of mind. I made a big pair of aeroplane wheels and placed them on the floor with the wheels suspended in mid-air. No one knows where it is going to land or what is going to happen when it does. People always want shortcuts, even at the price of sacrificing the environment.

Once you enter the exhibition, you will see another work entitled Fireworks. The shape of the piece resembles corridor windows from traditional Chinese gardens. However, in the place where the windows should be I painted fireworks at the moment before they are extinguished.

Monica Merlin: You rarely paint. These pieces show another side of you.

Yin Xiuzhen: I studied oil painting and I actually enjoy painting a lot. Every time I visit an old classmate and smell the paint, I feel nostalgic, because it reminds me of the smell of my university classroom.

Monica Merlin: Do you think you may paint more in the future?

Yin Xiuzhen: It depends on the work. Fireworks needed painting. But I can get tired of painting sometimes. Song Dong knows about this. When I stopped painting, he asked what had happened. I said, ‘I cannot bear it any more. I need a break.’ I guess this is because I think about a lot of things when I paint.

Once you have passed the fireworks in the garden corridor windows, you will see a ‘diamond’ – a work called Black Hole. On the diamond, you can see brand logos and popular phrases printed on clothes, representing what people want and desire. Inside the diamond, there is some lighting. This is the second diamond that I have made. The first one was made in New Zealand with a freight container. I cut open a freight container, made it into a giant diamond and put it by the sea

Yin Xiuzhen

Black Hole 2013

Installation with multi-layer board, used clothes, LED lights

150 × 250 cm diameter

© Yin Xiuzhen, courtesy of Pace Beijing

Monice Merlin: Are the clothes used in this exhibition second-hand?

Yin Xiuzhen: They are second-hand. I prefer second-hand clothes.

Monice Merlin: How did you get them?

Yin Xiuzhen: My friends bring bags of unwanted clothes to me when they visit. They know I always collect second-hand clothes. My family, my sister and her children also collect second-hand clothes for me. People’s lifestyles are different now – they always want to keep buying new things. I put those unwanted clothes in my storage and sort them out for my works.

Monice Merlin: Did you make these works all by yourself or did you have someone to assist you? It seems like a lot of hard work.

Yin Xiuzhen: There were two types of work. One was sewing, which I got some people to help me with. The other was working with wood and metal, which I could not do myself and I got a factory to do instead.

Monice Merlin: You are having another exhibition in Philadelphia now, in collaboration with Song Dong and your daughter. Could you talk about those works and their significance?

Yin Xiuzhen: We have worked on this series for ten years. When Chambers Fine Art first invited us to do an exhibition, Song Dong and I did not see a reason to collaborate. They said that we could either exhibit as two artists or collaborate. We did not understand why they wanted us to collaborate, because we had never collaborated before – we were used to working separately. But then we discovered a reason to collaborate: to celebrate our tenth wedding anniversary. Soon afterwards, I got pregnant. The exhibition was in 2002 when I was seven or eight months pregnant, and we thought it would be interesting to collaborate on something to commemorate this.

In the beginning it was not clear how we were going to collaborate – whether I should make my work and he make his or whether we should conceive of the work together. In the end, we collaborated on the piece Chopsticks. We agreed on the size and shape of the pair of chopsticks, made one chopstick each independently, and then showed it to each other as a surprise on the day of exhibition. It was fun. The second exhibition was called The Way of Chopsticks. We had both stubbornly insisted on our own idea for how we should use a cot. For this work, we cut a cot into two halves and worked on our own half separately. We thought it was an interesting concept, to make the works separately without interfering with one other, and then place our works together only at the exhibition stage. The title The Way of Chopsticks implied a way of collaborating without too much constraint. All we needed was a common subject and then we could develop our own individual ideas. We also collaborated on videos such as Left Hand, Right Hand as well as some paintings.

What made Philadelphia [The Way of Chopsticks, Philadelphia Art Alliance, 2013] so novel, was that our daughter joined us. At the first collaborative exhibition she was still in my belly – by then she was 10 years old. She found our discussions at home interesting and wondered why we kept our work a secret from one other. She said, ‘It’s fun! I want to join you!’ She participated in one of the works and made a third chopstick. The three of us agreed on the basic shape and made it separately. My studio is big so each of us had our own room to work in. We did not see one another’s work until the day we finished it.

Monice Merlin: What did your daughter’s chopstick look like?

Yin Xiuzhen: We decided that on a specific length but left the shape open for her to decide. My daughter had some help with it and she produced some instructions for a manufacturer to make the chopstick. She had seen the chopsticks we made before, because we had a pair at home, so she requested that the overall shape of her chopsticks be made like our ones, but then she painted on them and added some dog hair – we have two big dogs. It was summer and the dogs were shedding hair as if they were shedding their winter jackets. She collected a lot of hair and made a ‘wolf’ chopstick – she really likes wolves. She loves art and started drawing when she was little.

Monice Merlin: Do you encourage her to make art?

Yin Xiuzhen: If she is interested, she can do it. If not, she does not have to do it. I said to her, ‘You can do whatever you want. You do not have to make art, but you must appreciate art.’ But from a selfish point of view, if she likes art, she will have more in common with us. Many kids do not want to chat with their parents when they grow up. If she makes art, maybe she will spend more time with us.

I kept many boxes of my daughter’s old clothes and toys. One day, she can look at these things and get an idea of how she grew up. They are not textual accounts, but they do document the past. They are nostalgic and carry our love for her. There are many stories in those clothes and toys. When I was young, my family was poor so I always picked up my older sister’s clothes once she had outgrown them. Then I passed them onto my younger sister. When my younger sister stopped wearing them, my mother would keep them just in case they could be used for making or patching other things; at the time, every family had a quota for buying fabric. Because she kept everything, when I became an adult I was able to see all kind of objects from my childhood. The reason behind why I keep my daughter’s things is different, but I preserve a history for her all the same. I believe she will be grateful for it in the future.

Monica Merlin interviewed Yin Xiuzhen at Pace Gallery, Beijing on 23 November 2013.

Published 21 February 2018