Xiao Lu

Photo: Monica Merlin

Monica Merlin: Can you talk about your ideas and experience around the time of the China Avant-garde exhibition in 1989? You became an important and sensitive figure in the art scene at that time. How did you feel about this?

Xiao Lu: Dialogue, the work I exhibited at the China Avant-garde exhibition, was my graduation piece. Because it was a graduation project, my teachers took an active part in the process, from its initial conception to completion. One of the teachers was called Maryn Varbanov. He is a Bulgarian/French tapestry maker who taught at the [Hangzhou] Art Academy while I was there. Sometimes I would take my artworks to him and ask for his advice, so he had an influence on my work at that time. Another teacher who had an impact on me was Professor Zheng Shengtian. In the beginning I wanted to do some paintings for Dialogue, but Zheng told me to use photos instead. So my teachers really contributed a lot of ideas throughout the entire process. After all, I had hardly any experience with contemporary art at the time. I had studied oil painting for so many years, and had always felt that I should paint, but Zheng told me to do an oil painting to meet the graduation requirements, but also make the Dialogue piece using photography. He said, ‘Just make it, and then we’ll see what happens.’

After I finished it, I actually did not send the work to the 1989 China Avant-garde exhibition myself. At the time I did not know the curators of the exhibition, Gao Minglu and Li Xianting, so I had no idea that I would be able to participate. Due to some personal experiences when I was young, I had difficulty relating to other people at school. I was not very close to others and I did my own thing.

At the time of the exhibition, I had already graduated and started working at the Shanghai Oil Painting and Sculpture Institute, so I was very surprised to receive a notice one day telling me that my work had been accepted by the China Avant-garde exhibition. I only found out why later when I visited Hangzhou and saw Zhang Jian, who told me that he had sent the piece on my behalf. Zhang was the editor of the magazine New Arts at the university, which had published an image of Dialogue around the time of my graduation exhibition. As the editor, Zhang had some slides of my work, so perhaps when Gao Minglu had asked Zhang to send him some good works from our school, he had decided to send my work.

My piece was also published on the back cover of Art Magazine (Meishu). The editor Tang Qingnian noticed my piece when he came to Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts to see the graduate show. Dialogue was able to capture his attention probably because it took a new approach in the atmosphere of the 85 New Wave. That is why they put this work on the back cover of the magazine. Perhaps this is how the piece had left an impression on Gao Minglu and the other members of the China Avant-garde exhibition organising committee. So, when Zhang Jian sent in the piece, they chose me. Otherwise, they would not have noticed it among so many other artworks.

So my participation in the exhibition was not self-initiated, and being in the exhibition was really unexpected for me. I had only just graduated and I somehow got this unusual opportunity to take part in a big exhibition. I did not have too many thoughts – I just wanted to make it good.

Then on the day of the exhibition, my decision to add the gun-shot element to the Dialogue piece came about quite unexpectedly. As a recent university graduate, I was quite respectful towards procedures and I wanted to report what I was planning to do. In the morning, I spoke about firing the gun to the only person I knew on the organising committee, Hou Hanru, who I knew through Maryn Varbanov. I saw Hou briefly but he was very busy and sent me away – probably thinking that he could disregard me because I was not particularly famous. If I had known Gao Minglu, Li Xianting, or anyone else on the committee, I would have talked to them. But at the time, I was an obscure nobody in their eyes, and a woman too. So I did not have the opportunity to speak to anyone about firing the gun before the exhibition opened.

Xiao Lu

Dialogue 1989

Image courtesy of the artist

I did not necessarily intend to do the gun firing the way I did. I really cannot explain clearly why I did it; it is as if the whole thing was predestined. So many things could have prevented it from happening, but in the end it happened. If I had talked about my plans to anyone on the organising committee, it probably would never have happened. I know that everyone who had told Gao Minglu their plans was not given permission to carry them out. At that time, the organiser’s ideas for the exhibition were not that advanced and radical.

On the opening day, Tang Song arrived at the museum just after I had fired the gun. If he was there just a little earlier, it probably would never have happened. There were so many coincidences on that day that eventually made the gun firing happen. Perhaps some people meticulously plan their work, but I am not like that. As soon as I have fixed upon something, I have to finish it, and during the process I just let whatever happens happen. I am not a very deliberate person and I just do what I feel like doing at the time. So that is how the gun firing came to take place on 5 February 1989.

One further fortunate thing is that I managed to get the performance photographed. While waiting on the square outside the museum, I saw an old classmate shooting videos. I told him that I was going to do a performance and asked him to photograph it. If not for this chance encounter there would have been no images of the performance. So, you see, a lot of coincidences.

At the time, I didn’t know anything about installation or performance art. I did Dialogue just because at the time I felt very stifled, really quite suffocated. I had a boyfriend but I could not talk to him honestly about my past. I was keeping a lot of things to myself. Even though we were living together as a couple, I felt like we were strangers and I couldn’t talk to him about anything. I felt like I could not communicate with men. Dialogue was about that.

Monica Merlin: Did you think he would not understand you?

Xiao Lu: No, I think the problem was with me. I thought that I could not talk to men because I kept so many things to myself. In my mind, these things were very dirty, so I could not talk about them. But you cannot stop thinking about those things overnight. When I was writing my book in 2004 I discovered that, from a psychological point of view, if you set something aside and do not deal with it, it just grows and grows like a cancer. You need to face it. So when I finished my novel, Dialogue, it felt like a release. Looking at it in terms of psychology, it is good for me to write it down and get it out. If I always keep these thoughts inside, they will stay and never go away.

When I look back at the works I have created in my life, I think all of them are about my hope to communicate and have an emotional relationship with men. I think that I have never been able to let out my emotions, so no matter whether it is Dialogue or any other piece, I know how I am feeling when I am doing it. I know very clearly that the works belong to me, but I do not know how to talk about them.

When I started, I would joke that your fame must be equal to your ability to endure it. The fame I attained after the 1989 exhibition was too much for a recent graduate. I was not prepared to face the situation at the time in terms of my experience and mental resilience. I was not able to talk about Dialogue. It is what it is, but I did not know how to explain it. Later I took political and social approaches to explain the work, but that felt very phoney. I did not know how to talk about my work so I did not speak at all. So that was my problem: I did not know how to deal with what was happening or the work itself. If a person has psychological issues, it will cause a host of other problems. So I think that psychology has a direct influence on art.

Why did this work cause so many problems and repercussions in the Chinese context? The 1989 gunshot is completely exceptional – it could not have happened at any other time. It was fired on the eve of the Chinese New Year in 1989, suggesting that there would be many more gunshots to come. Regardless of how society perceives this work, the work has its own life. I created it at a particular place, at a particular time, and in a particular historical context. That is why it caused those particular consequences. You should not mix the work with its consequences. Now in China people often confused these things. If a work is political or social, then you are not allowed to say that it is a work born out of the artist’s emotions. If you say it is the product of emotions, then you are accused of trivialising it.

Monica Merlin: This is also related to traditional views of women – they say that women artists’ work is always closely related to their emotions so whatever they choose to convey is only related to these emotions. Sometimes it is true, but there are other sides to it, and more complicated thoughts going on.

Xiao Lu: According to this theory, Dialogue, which was born out of a woman’s emotions, is simply worthless. The same work, however, is deemed extremely meaningful and valuable when Tang Song added his political and social interpretation, saying that it tested the flexibility of Chinese law and so on. It is the same piece of work – created at the same time and at the same exhibition – but if you change the way you talk about it, suggesting that it does not involve politics or social impact, the work suddenly becomes worthless. This is the context for Chinese contemporary art. And if it is made by a woman, it is deemed to be worth even less.

Monica Merlin: But for me, looking at the history of Chinese contemporary art, I think your piece and your performance in 1989 signal a very important moment. It was a historical milestone in two ways: firstly, it broke new ground in contemporary Chinese performance art; secondly, it is a statement that female artists do exist in China. Were you thinking about the situation of female artists back then?

Xiao Lu: No, I was not. Today there are many female university students, as well as many female art students. But back then, I was the only female student in my class.

Monica Merlin: Did the 1989 exhibition feature any other female artists?

Xiao Lu: Yes, Xu Hong and Huang Yali. The latter is a sculptor. There was also a woman who did traditional Chinese paintings. But there were only a few women. Among the female artists, my work was probably the most striking.

Monica Merlin: This was an important piece and it represented what women artists could create.

Xiao Lu: If you tell Chinese men that a woman made the most important work at the 1989 China Avant-garde exhibition, they would not agree! This is a man’s world, you know? It is terrible – I think on a psychological level, the men would not be able to accept this fact.

Monica Merlin: What do you think of the current situation for women artists, and women’s rights more generally, in society?

Xiao Lu: To answer this question you can look at my video works, which are mostly personal. Two years ago, I suddenly felt quite lost and my work started to change. I started to let go of some emotions and they stopped bothering me. As I went on, I started to think about how to do my work. Over the past two years I have begun to use a different process. Until Love Letter all of my works were related to my lovers. They changed somewhat after that. I am very grateful to Li Xinmo, Xu Juan and Lan Jing for getting me involved in the Bald Girls exhibition [Iberia Center for Contemporary Art, Beijing, 2012]. They found me when I was in the midst of a change. I am the kind of person who goes with the flow of life and deals with things as they come up. So when Xu Juan – the curator – came to me and said she had chosen three of my works – Dialogue, Sperm and Wedlock – for the exhibition because they showed a feminist consciousness, I simply admitted that I had not thought about feminism when I created them. But she said, ‘It doesn't matter. I can write about them from a feminist perspective.’ And I said, ‘Sure, write on!’

Monica Merlin: But when you look at your work, do you not feel that the connection to women’s rights and women’s experiences is quite obvious?

Xiao Lu: Wedlock and Sperm were both born out of my personal experiences. After the curators of Bald Girls approached me the year before the exhibition took place, I bought a lot of books on feminism. That was the period when I researched the history of women’s rights. This experience changed me. Now I look at the work that I created for the exhibition and think it was probably not the best, but in the process of making it I underwent a change.

I just told you that I read many books on feminism prior to the exhibition, but actually, I did not read them in great detail; it was just for an overview. Nonetheless, it triggered a change in me. Before, I had always been concerned with my own personal experiences, but after Bald Girls I started to pay more attention to the lives and experiences of other women. My works were no longer exclusively based on my own situation. This was the transformation.

But as to where my work is heading now, I think I still need more time. That is because thinking about other women’s experiences is less direct than thinking about myself. With my own troubles, I know where it hurts, so I can immediately find the right spot and make it into a work. But if the work is about other people, I need to read about related issues to understand them. I have also started taking pictures or videos of other women. This is a new subject in my art practice.

My approach is really different now. My works before were primarily about myself and my experiences. Previously, my work had been about externalising the internal. Now perhaps I am internalising the external, and then externalising it again. So I think that the Bald Girl exhibition suddenly opened a window for me.

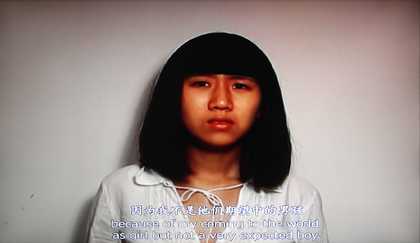

That was actually only the start. I made the piece What is Feminism? because feminism was a completely new thing for me. I did not have a thorough understanding of it at that time. I had read some things, but I was not like other women who had studied feminism for years. It was an entirely new subject for me. So in What is Feminism? I was asking not only the audience, but also myself.

Monica Merlin: What is your answer to that question?

Xiao Lu: It cannot be answered clearly in one sentence. I could try to answer this question for the rest of my life, but I think that part of it is that women should understand their value in society. For the first half of my life, I lived almost entirely for men, tied down by my emotions. Even though I managed to make some art, I did not feel the value of it. What I valued most was recognition by men. I might have received a lot of recognition from society, but at the time I did not care. When you attach so much importance to the opinion of one man and he ends up not thinking highly of you, you feel like the world has collapsed.

I think ‘women’s rights’ has many layers of meaning. First, a woman must find her own value and retain her independence, regardless of the relationship she is in. I know this now better than any other time. I will not mentally rely on any man to that extent again, even if I am in a relationship. I figured out another thing from my recent experiences – women must be empowered. In China, the world of critics consists exclusively of men and they are the ones who have the authority to speak. So when a woman encounters an issue, she has nowhere to turn to, no one will listen to her. In China, when something bad happens to women, they feel pain in the moment, but then forget about it afterwards. So I think I need to tell other women that they should fight for their rights before something bad happens.

When I did the Bald Girls exhibition, I said that women should help women. Every successful man is supported by countless women behind the scenes. Women help men, and men help themselves and each other. Why are women so weak? Women rarely unite among themselves for a common cause. Women are too self-absorbed. They centre themselves around their families and their emotions. Women are often out of touch with society. Men actively participate in society, whereas women do so passively. So when women want to achieve something in society, they may have already been dragged down before they even begin.

I am not someone with great desire for power or a high level of sensitivity to power, but if I have any power to speak, I will speak for all women. I think women need more help. Through my work, I have supported women’s rights, for example, by participating in the Bald Girls exhibition. Later, Guangzhou University invited me to give a lecture about my experiences. They said, ‘We are very glad that you are finally beginning to talk about feminism, Xiao Lu.’ ‘Feminist’ is an annoying word in China. Men really dislike it. But I told them that I am not afraid to be called a feminist if they needed to call me that.

Monica Merlin: I think what they dislike most is the ‘ism’ in feminism.

Xiao Lu: Yes. This does not bother me. In the West, feminist movements went through a stage of confrontation in the 1960s. China hasn’t gone through a historical stage like that yet. But the problem in China is severe. After reading many books, I realised that women’s rights are ultimately human rights. I think that in the West, women’s rights developed alongside human rights. Because if you demand respect for every human being, this includes women automatically. In Chinese society, there is no respect for individuals, let alone for women.

I once joked that in China an exhibition openly celebrating human rights would be shut down after three minutes because the phrase ‘human rights’ cannot be mentioned. When we did the Bald Girls exhibition we openly used the phrase women’s rights, but our exhibition was not shut down, which shows that in Chinese culture women are not paid attention to. When women fight for women’s rights, men are not alarmed. They will say, ‘The women are being silly and making a scene. Not a big deal.’ So our exhibition tested the status of women and women’s rights in China. Given what it showed, I think it is vital to promote feminism here.

Monica Merlin: Are you still collaborating with the Bald Girls artists?

Xiao Lu: I just spoke to them yesterday. Next year ‘the Bald Girls’ will form a unit of an exhibition at the Frauen Museum in Bonn with the theme ‘single mother’. Museums abroad like the Frauen Museum tend to plan programmes well in advance, but they inserted us into their upcoming exhibition because they think what we do is relevant to the theme.

Monica Merlin: Can you tell me about what happened at the Venice Biennale? You staged a piece of performance art and you were not welcome there.

Xiao Lu: They will never allow me to go back.

Monica Merlin: It showed how the Catholic Church sees art and life in a narrow-minded way. I was surprised that they agreed when they knew what you were going to do.

Xiao Lu: First, I dug up a large bucket of mud from the Grand Canal in Beijing, which I then freighted to Venice by sea. I planned to smear my body with it. When I told people at the church about my idea, they agreed that I could only do it outside their gate. But they changed their mind at the last minute. On the day before the performance, they stole my mud. They probably knew that I had fired gunshots in the past, so they became fearful that I would use the mud inside the church anyway. I was very angry at their decision.

In my performances, there are often accidental elements just like this one, and I am always left with having to make a last-minute decision about whether the event can go ahead. In this case, I decided to do the performance in Venice anyway and see what happened. Swimming was not the important part; the key moment was when I stripped off in the church. Everyone at the exhibition saw me.

A guy called Wen Cheng was at the performance and he took lots of photos. Later, he included my work in an exhibition he curated at the Central Academy of Fine Arts, which reviewed China’s art presence at the Venice Biennale over the past twenty years. He said to me that day, ‘I have a feeling that you will be in trouble, Xiao Lu.’ One of the photos he took of me that day showed me sitting under an arch staring at the sky. At that moment, I was actually wondering if I should do the performance or not. As I had prepared my outfit, it would have been easy to carry it off. All I would have needed to do was to strip off my shorts. But I needed to make a decision. Despite many years of being an artist, I had never stripped naked for a work. There had never been much nudity in my work. I was fifty years old and my body was not beautiful, so I felt some pressure. But then I thought to myself, ‘It does not matter. Just be yourself. This is my body at my age and it is a unique language.’ So I walked over and stripped off my clothes before the director of the museum could realise. He tried to speak but he was floundering. I ran very fast, and it only took me a few seconds to dash out. Church officials shut the door and made an announcement saying that the place needed to be purged because I had blasphemed the purity of the Catholic Church. I heard that they actually cleaned the church on the following day because I had made it dirty. They declared that I was not welcome there anymore.

Monica Merlin: I think your performance is of great significance. You know that the Catholic Church is not particularly open-minded.

Xiao Lu: Catholics tend towards chauvinism, whereas my work was very feminist.

Monica Merlin: Your original idea, to which they gave permission, was about the environment, nature and other subjects. But I think that the final result was even better than the original idea, because it opposed the male chauvinist tradition of the Catholic Church. I think that this opposition is important; I know it because I am from Italy.

Xiao Lu: Was the course of civilisation in Europe all about fighting against religion?

Monica Merlin: It is complicated, particularly in Italy. The Vatican bears great influence on Italian politics. Because of the Vatican, the Catholic Church is very powerful. So I think that works like yours are definitely meaningful in Italy.

Xiao Lu: It was a way of rebelling. I think doing performance art requires the right time, the right place and the right person. For my piece at the Venice Biennale, a religious venue in Italy was the right place. The performance could only generate great power when enacted in such an environment. In this context, the work can be about women’s rights. After I was kicked out, I said to the church officials half-jokingly, ‘I saw so many naked women in your churches in Italy. Why can you not accept my nudity?’ They said, ‘The nudity in church paintings is used to tell religious stories and is pure.’

Monica Merlin: Actually, they usually do not show nudity, though the figures may wear loose and revealing clothes.

Xiao Lu: But Italy is the most conservative European country, right?

Monica Merlin: Definitely one of the most conservative, together with others in the Mediterranean area. But because of the Vatican, the situation in Italy is unique. The Vatican has huge influence on the Italian government and society. But the current Pope Francis seems rather progressive, and more open. He said something about homosexuality, stating that love is love and that he did not want to condemn gay people. I think that is some great progress. Of course they will never allow gay marriage – not for the next 500 years. The changes in their conservative view will be very slow.

Xiao Lu: Since the Venice Biennale has been going on for so many years, there must have been many bold artworks that challenged the church. Why do you think that they did not influence the Catholic Church?

Monica Merlin: There have been works that referred to or even opposed Catholicism and other religions. But in your case, the venue was particularly sensitive.

Xiao Lu: If it were in the main exhibition halls, it would probably have been fine.

Monica Merlin: Exactly. The space that you used was very interesting. Since they should have been familiar with the type of art you made before, it was strange that they even allowed you to do it outside the gate in the first place. What they did later was unfair to you.

Xiao Lu: They stole my mud, which I transported all the way from Beijing. Perhaps they thought I would give up. But when a crucial moment like that happens, I can be a rebel: the more you oppress me, the more I will fight back. This is something to do with my character. For a lot of women in China, if you keep oppressing them, in the end they will stay silent. But I will always fight back: you can see a spirit of resistance in many of my works, including Fifteen Shots and Sperm. It is in my character. Even if you oppress me and apply a lot of pressure, I will still resist you.

In Venice, they blocked every possible way I could produce the piece and they were not open to negotiation. There was no time for me to ruminate – I had to decide immediately what to do. So it was my character that prompted me to make that decision. I could have called the entire thing off, but the rebel inside me chose to go ahead.

Monica Merlin: Can you talk about your recent performance pieces or other new works?

Xiao Lu: I did a performance piece called The Skin Paper Room a few days ago in Shanghai. I fasted for seven days and seven nights, sustaining myself only by drinking water. During the seven days, I stayed in the same room, painting and writing. The third day was very hard. I wanted to challenge my physical feelings. When chatting with an old traditional Chinese doctor, I learned that fasting, when done in conjunction with drinking water, is actually good for your health because it allows the body to cleanse itself. But the doctor said I probably could not do it because I was too old. I was curious and wanted to try it anyway. He then advised me that seven days is the limit for an average person to survive on only water. At the time, I was invited to do a performance, so I thought I should try this idea. There was 24-hour CCTV surveillance of the space, so that should anything have happened, I could have been taken to hospital as soon as possible.

Monica Merlin: How did you feel afterwards?

Xiao Lu: I felt a bit weak right after the performance was completed. Three days later, I was taken to the hospital. I actually had a kidney stone. The doctor told me that drinking so much water during the performance washed the stone into the protonephridium, which was causing a lot of pain. But the stone was removed and I am fine now. If it was not for the fasting, I would have had no idea that there was a stone in my kidney.

Monica Merlin interviewed Xiao Lu in her studio-home in Beijing on 12 November 2013.

Published 21 February 2018