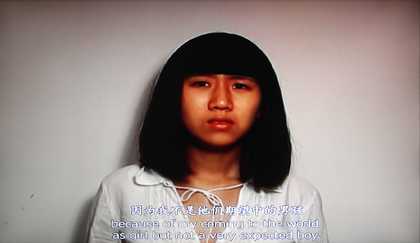

Han Yajuan

Image courtesy of the artist

Monica Merlin: Let’s start from when you graduated. What were the ideas behind your early works?

Han Yajuan: I will actually begin with my education. I went to an art high school and then an art university. There was no break during this time, and things went very smoothly. At university I studied oil painting, which was considered to be elitist, and modern art. Between 1998 and 2000, experimental art in China was only in the early stages. Someone happened to send me a video camera as a gift and I started making short films and video art. Because of my academic background in oil painting I was not particularly interested in contemporary art at first, but it was my experience in making short films that drew me to contemporary art. I enjoyed making videos and I carried on for two or three years, taking part in various contemporary art exhibitions and events. Later, however, I did much less video art, mainly for two reasons. Firstly, I was still a full-time student. Secondly, after seeing many high-quality, interesting video works by other people, I felt that as a student I did not have the money to achieve the desired effects. Without the right equipment, it is difficult. Very often, I had very good ideas, but I had to convey them in a rather crude way, a lot of the things I wanted to do were simply not possible with my resources. Video felt beyond my grasp. I gradually felt disappointed with making videos, so I went back to oil painting, which was something that I could do well at the time. It just so happened that around the same time I got into an MA programmeme in oil painting, so I turned my focus on painting again. But during my MA programme, I also made some video work every year, because I still liked it, as much as I liked painting. I found a good balance between the two.

Monica Merlin: After you graduated, what did you want to express in your paintings?

Han Yajuan: The central goal of my art is to provide a space for the expression of my perception of the world. My early pieces came from close observations of people around me – the ways in which I saw them and how they could represent my own life. Later, in the middle period, I began to paint from a bird’s-eye perspective. I started to step back from close-ups to look at life and myself. Later, my perspective changed again, from bird’s-eye to ‘multi-space’, which is a way of looking at life and existence from another dimension. Even recently, I have still been making changes in my work, which I will talk about later.

So this is how my work has evolved. If you ask me whether my work is related to society: of course, it is. But it is a particular kind of relation. For example, it is not the case that as soon as I learn about pollution issues, I will go and paint it. There is always a thinking process, and only afterwards comes the expression. In other words, my expression at every stage is not only influenced by society, but is also closely related to my own perception.

Monica Merlin: Most of your paintings feature women, from young girls to adults. Can you talk about why you mostly paint women?

Han Yajuan: Perhaps because I am a woman myself, and because I think that my take on women is objective. I always try to present subjects from an objective point of view. Being a woman, I am inherently limited in my knowledge about men, and thus cannot understand male issues objectively. So seeing things from a female standpoint is the only objective point of view I have, and I decided to observe and express my ideas from this point. My early works received a lot of attention because they are the expression of what I see from my point of view, and my perception of the surrounding world – they are observations and representations of the circumstances, hopes and concerns of a whole generation of girls.

Han Yajuan

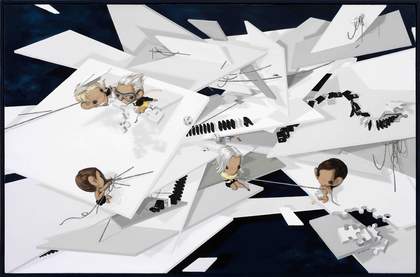

Quantum Leap No.02 2012

From the ‘Transcendence’ series

130 x 85 cm

Courtesy of the artist

Monica Merlin: In your early works, we often see a cow. Is this a symbol?

Han Yajuan: Yes. Because cows are all female, they become a symbol for women in my works. Moreover, there is a mutual gaze happening between the women and the symbolic cows. They project themselves onto each other and reference each other.

Monica Merlin: You have been an artist for seven or eight years now. The girls in your paintings have grown up too, almost as if you are growing up together. Does this reflect the course of your life? From your twenties to thirties, has there been any change in the way you look at the world?

Han Yajuan: There have been major changes and they took place very naturally. If you only compare the works I do now with those from seven or eight years ago, you see a really big change. But even within those years, my works varied a lot and I explored different issues at every stage.

Monica Merlin: Why did the changes happen?

Han Yajuan: In short, it is because my perception of the world changed – it became deeper over the years. And that in turn is because I got to see more things, reflect on more issues, read more books and do more research.

Monica Merlin: Is there a book, person or subject matter that has influenced you recently?

Han Yajuan: Looking at my works from the beginning until 2011 you can see the process. In my early work, I observed from a close distance the existence of my subjects and their relationship with the unknown. In the middle period, I tried to be a spectator and provide a higher perspective as if I were looking down at my own life. Later, I started using multiple spaces and multiple perspectives. At this point, my work was not realistic or about real existence any more. I discussed the impact of the unknown on us.

As discussed earlier, my works before 2011 went through three stages, during which I enlarged my perspective from close-up to multi-space. After 2011, I enlarged my perspective even further. I discovered that all the points of view I had previously adopted in my work were are all linked to my way of thinking. No matter how much I tried to provide an objective perspective, the works were all based on my own way of thinking, which is in turn influenced by society. So I started questioning these points of view. Their truthfulness is in doubt, because they are influenced by authority. For instance, even knowledge itself is a kind of authority. One’s way of thinking can be influenced by such an authority and follow a set pattern. I began to question the ways that people think.

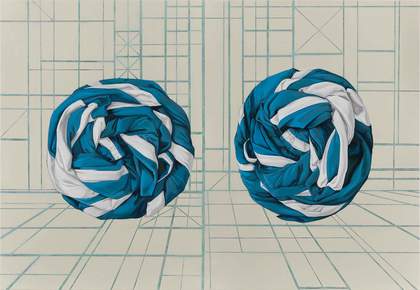

Han Yajuan

Lean on 2015

From the ‘Superlative’ series

Oil on canvas

140 x 95 cm

Image courtesy of the artist

Monica Merlin: Many people said your works are about consumer culture. What do you think of that?

Han Yajuan: If you have only seen certain works of mine from a certain stage of my career, you might say so. But if you have seen the whole process, you would have a different understanding. Actually, I do not care what others say. For instance, say I make a hexahedral to represent my perception of the world. Some people see three faces, some see six, and others see nine or even more. But I am offering six faces because it is my perception at the time. What others see in my work is their perspective. I hope those who see three faces can think about the faces that they have not seen. As for those who see eight faces, I would like to exchange ideas with them as well.

Monica Merlin: I can see in your paintings that you are concerned with the social pressure placed on women. Can you talk about it?

Han Yajuan: There is a lot of pressure. Society puts pressure on both men and women – different kinds of pressure. Also, we face different types of pressure at different ages. Which type of pressure would you like me to talk about? Regarding this, I have my own opinion, which is not necessarily connected to my paintings.

Monica Merlin: You can talk about any type of pressure you like. It can be from your own experiences, regardless of the connection to your paintings.

Han Yajuan: One type of pressure on women is having babies. For example, if I wanted to have a baby. I would have to stop painting. This is a very realistic conflict – I would probably have to stop for one or two years, but there are many things I want to make and I do not want to stop. So, being at child-bearing age is a big pressure for me. And this is a problem every woman faces, with social pressure coming from their parents and their families. Women are thus forced into a dilemma in which they have to choose between their careers and having babies.

Monica Merlin: What is the position of women artists in China?

Han Yajuan: The position of women artists is defined by men.

Monica Merlin: Do you find any difficulties in this situation?

Han Yajuan: It depends on how you see it. I do not think things have gone so far as to become ‘difficult’ for women artists. The overall situation in China does not have a direct, immediate, or visible effect on women artists’ lives, but it does pose difficulties for them. It is similar to how pollution affects our lives. Pollution won’t affect our lives immediately, but it is part of the overall environment in which we live and it could have a negative impact on our lives without your awareness. So for women artists, even though the environment won’t affect them directly, they are still under its influence.

Monica Merlin: The female bodies in your works are usually beautiful and attractive. Have you idealised them?

Han Yajuan: They are idealised, because I always celebrate positive things. It is not possible to achieve perfection every day, but you need to be happy with yourself. There is a need for that self-satisfaction in our society, because our education tends to make us lose confidence in ourselves. A woman might not feel comfortable about herself. The sense of self-satisfaction is crucial to everyone, regardless of their race, education and origin. You need to understand and be happy about your identity, and the position and value you hold in the society. I always want to emphasise positive things like this in my work.

Monica Merlin: What do you think is the relationship between women and famous brands? Because I can see luxurious fashion, cosmetics and travelling in your paintings.

Han Yajuan: Those things can help make your life more ‘perfect’ and give you a sense of comfort. Famous brands are important in certain phases of one’s life. Once you have passed through these phases, you will probably have other pursuits. But brands can be important to you in certain phases. For example, speaking of luxury, in my parents’ generation, which is about thirty years ago, bikes were a luxury. Now they have ceased to be a luxury, but maybe some time in the future, cycling will become a luxurious lifestyle choice again. In my work, people can see consumption and material goods. Just as I said, they exist physically, but how people see them will change.

Monica Merlin: What are your recent works like?

Han Yajuan: I mentioned that I started considering new ways of thinking. For instance, cognitive theory and how we perceive the world. I care about things unknown to me – the ‘unknown things’ and the ‘unknown space’ – and their relationship to us. This is actually the essential motif of all my works. As I said, I started questioning ways of thinking, because the perspectives I had are based on a certain logic. Taking a step back, I realised that there is not one universal way of thinking. A primitive man had a different way of thinking from ours because humankind’s cognitive systems have developed. The way of thinking in Zen Buddhism is totally different too. Our current ways of thinking are influenced by various authorities, and they pertain to every aspect of life, including the status of women and the issue of pollution. The root of our current thinking is dictated by an authority, which can be a group of people or even just one person. This is what I was starting to question.

But I did not know where to go next. One day I had a sudden realisation. It is actually very simple – I only needed to take a step back into daily life. I decided to use commonplace things to convey my questioning of people’s ways of thinking. For example, the subject matter can be a person breaking a piece of bread and finding rice inside. It is not what one expects. Many things have hidden spaces inside, which remain secretive and undiscovered because your perception does not enable you to see them.

There is another important facet in the evolution of my work. My early works are relatively simple, yet, as I progressed I began to add more to my compositions, until one day I suddenly had a realisation. Just because you wear a qipao, you don’t automatically become a traditional Chinese artist. Your aesthetics are acquired unconsciously. Do you know the famous Chinese painting Along the River during the Qingming Festival? It is a long scroll painting that depicts a large crowd of people in a very busy scene. If we compare this painting with a photo of a starry sky, which one do you think contains more information? For me, I suddenly understood that a seemingly empty photo might say more than Along the River during the Qingming Festival can. This was a turning point that brought me to choose subjects drawn from daily life. Instead of ’addition’, ‘subtraction’ became my approach.

Monica Merlin: Is there an artist who influenced your approach or thinking?

Han Yajuan: There are many artists whom I like, but I won’t paint the same things as they do. For instance, I like Albrecht Dürer very much. It sounds weird but I think my paintings are similar to his. I think our sense of precision is similar. So there is no doubt that I am influenced by other artists, but I never try to purposefully learn from any of them. Because the thoughts behind my works do not come from art itself, but from a broader realm. I always try to place myself in the wider world, rather than being constrained to any particular region. Of course practically I still need visas to go anywhere, which is very inconvenient. But I try to see and think about things from a wider perspective. That is why I said that my art is the expression of my perceptions, acquired not from art itself, but from many other things.

Monica Merlin: I noticed a book on feminism on your bookshelf. What do you think about feminism?

Han Yajuan: I think it is more natural if we do not single it out for discussion. Do you see what I mean? When you try to emphasise it, it is unnatural. Plus, feminism itself is based on Western theories. Personally, I would rather face this issue in a natural way.

Monica Merlin: What do you hope or expect the viewers to feel or think when looking at your works?

Han Yajuan: I am an artist and I am doing my job. I am not trying to give anything to others. I am just doing what I am supposed to do. In terms of the effects that I hope to achieve, as I mentioned earlier, if I built a hexahedron, I would hope that those who could only see three faces would at least think about the other faces. Living in such a fast-paced world, few people will think about origins. When we are children, we care about where we come from. When we grow up, we are swallowed into a social system and we do not have time to think. But actually, the questions about origins directly affect how we position ourselves. Like I said, you need to be comfortable, satisfied with yourself and proud of who you are. Many people lose sight of the significance of this and some do not even have the time to think about it. Of course I cannot force people to think about it, but I hope to encourage them to begin to do so. I am doing what I can as an artist: I present my thoughts in an artistic language, hoping my works can inspire others because otherwise they would be meaningless.

Han Yajuan

Nerds’ Philosophy 2015

From the ‘Superlative’ series

Oil on canvas

90 cm diam.

Image courtesy of the artist

Monica Merlin: There seems to be a strong link between your works and cartoons. Did you grow up reading cartoons? What is your relationship with cartoons?

Han Yajuan: The influence is mutual. When I was growing up, I saw a lot of cartoons and liked many of them, such as films by Hayao Miyazaki and some old Chinese comics – some of the early ones are very pure. Back then many of the cartoons were created elaborately with ink painting, but unfortunately they do not exist anymore. The comics or cartoons nowadays are neither fish nor fowl. They are shanzhai – fakes or imitations.

Monica Merlin: A big difference between comics and your work is that your work does not have any text. So I have to imagine what the characters in your paintings think and say. I find it to be an interesting process that stimulates my imagination. Different possibilities can be created with different viewers. Do you agree?

Han Yajuan: It must be true if you say so.

Monica Merlin: When you paint many women together, are you concerned with their emotions and their thoughts?

Han Yajuan: That is a must. Many years ago when I was in middle school, I read a book called Sophie’s World, a very famous novel. It says that the universe is like a magician, and you are the rabbit in the magician’s hat. My role is like that of a magician – I create a world with the rabbit in the hat. I present this perspective to you, which I hope will make you think about how you should look at your life if you were the magician. I hope it makes sense if I put it this way.

Monica Merlin: Are you trying to engage your viewer to create their own stories around your paintings by suggesting different possibilities of what your characters may be thinking or feeling?

Han Yajuan: I certainly leave space for imagination, especially in my recent works. I always believe that although my works appear like cartoons, they are actually very realistic. By realistic, I do not mean that the figures in my paintings resemble real people. Rather, I mean that the relationship depicted between the individuals in my paintings and their existence resembles real life. The visual language that I choose is inevitably influenced by cartoons, but it is hard to say whether I chose the language or the language chose me. I liked cartoons to a certain degree at a certain stage of my life, and it is impossible to argue that they had no influence on me. But the key is how I utilise this influence to serve the themes I hope to express in my work.

Monica Merlin: In your paintings women are mostly together with other women. Do you think a woman’s best friend would be a woman?

Han Yajuan: There are two reasons why I chose to focus on women in the beginning. The first reason, is that I think my perspective as a woman is more objective. I cannot observe or think about the world from a male’s perspective. So I perceive life in the only way I know how. The other reason is the feminist concern you talked about. Even though I want to see things from a broader perspective, and to present it naturally without singling feminism out, the issue of women does exist. That’s why I want to give more attention to women.

Monica Merlin: So where are the men?

Han Yajuan: In your imagination.

Monica Merlin: Is there anything else you would like to talk about?

Han Yajuan: I want to talk about many other things. Today’s conversation focused on me being a woman artist, how society influences me and my relationship with society. But because I haven’t seen you for many years, I would like you to gain an understanding of the evolution of my art, where I am today and how I got here. However, I am happy to talk more about women if you like.

Monica Merlin: One more question on your past then. Going back to something you said before the interview, you mentioned that when you were growing up, for a long time you did not wear dresses or skirts.

Han Yajuan: I did not realise or accept my social role. I always wanted to be outstanding in everything, for instance, in school exams. This mentality was caused by my understanding of social roles. I did not feel I was different from a boy, and no one ever told me that I was. Only when I entered society did I discover that my understanding of social roles was not realistic. I realised that as a woman I have my social role and I am physically different from men. It is nothing to be shameful of. It is natural that the world has both men and women. But this understanding of gender is missing from our education.

Monica Merlin: Is it the result of Mao Zedong’s concept of gender equality?

Han Yajuan: Even though there was a concept of gender quality, Mao Zedong did not follow through by building a value system of gender equality in the society. So when a woman enters society, she would find it hard to adjust to how things actually are in the society. She has to re-understand her social role, and the value system she has had for many years would be undermined.

Monica Merlin: Was there a particular incident that brought you to this realisation, or was it a gradual process?

Han Yajuan: It was the accumulation of many things that led me to a sudden realisation.

Monica Merlin: When did the realisation happen?

Han Yajuan: At university. Before that, my life was relatively simple – studying and painting at school, and that is it. However, when I was at university I was exposed to more information, especially as this was around the time the internet was becoming widely used. Also, at university I met a lot of people, some of whom I had romantic relationships with – back then, students were not allowed to have romantic relationships in high school. Before university, contact with the opposite sex was pure friendship, nothing more than that. At university, the increased contact with the opposite sex contributed to my intellectual growth.

Monica Merlin: Do you think the education system remains the same today in terms of what they teach about men and women? Or do you think the younger generation today have a different experience than the one you had?

Han Yajuan: Certainly not the same, because times have changed. Young people nowadays have more channels of information and they mature at a younger age. Unlike us, their resources are not constrained to school, parents and their immediate circle. The world used to be smaller but the internet has expanded the world by providing access to information. Today’s young people must have quite a different experience from me, a much better one. They see more, have more choices and understand more. Back then, I did not have that many choices due to the lack of resources.

Monica Merlin interviewed Han Yajuan in her Beijing studio on 9 November 2013.

Published 20 March 2018