Cui Xiuwen and Wawa in her studio, November 2013

Photo: Monica Merlin

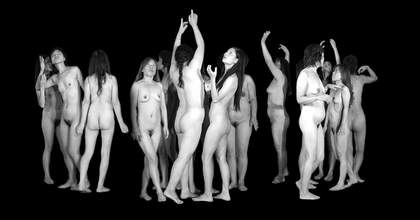

Monica Merlin: Let’s talk about your 2011 video work Spiritual Realm. Who are the performers?

Cui Xiuwen: They are ordinary people.

Monica Merlin: Are they people you know?

Cui Xiuwen: No, a model agency helped me find them. Some are full-time models at art academies, some are actors for movies, and some of them do modelling part-time while working in business. Lots of people are willing to do modelling work – they think it is a way to be involved in art. There are also many young people, actors and poets – all kinds.

Monica Merlin: Did you tell them you wanted to use nudity in your work?

Cui Xiuwen: Yes.

Monica Merlin: What did they think?

Cui Xiuwen: It was not a problem.

Monica Merlin: Did you tell them to move freely or did you direct them?

Cui Xiuwen: No, it was not like that. Even though I used nudity, my purpose was not to show their bodies. It was not about being beautiful. I was hoping that they would go back to the original, natural state of humanity. Wearing clothes is about your social identity and your naked body is your natural identity. I wanted them to return to the state of their natural identity, and then to feel their relationship to the world and the universe – to put themselves out there spiritually, to explore the universe and see how far they could go down this route. This is what I asked them to do.

The models had to possess the ability to perceive the spiritual world. I tested 100 models, but found that only around twenty of them were eligible. I kept those twenty people. It had nothing to do with their identity, age or profession, as long as they had this ability. Later, I discovered that, actually, having this ability has nothing to do with a person’s education; it is a natural gift.

I think, despite the fact that China’s traditional culture has been blotted out for over 100 years, its essence – such as the spirits of Laozi, Mengzi and Confucius – has been passed down to today’s generation thanks to ordinary people. All these people have a special ability, but they have not yet realised it. It is not just academics or scholars who have this skill; ordinary people do too.

Cui Xiuwen

Spiritual Realm 2010

Image courtesy of the artist

Cui Xiuwen

Spiritual Realm 2010

Image courtesy of the artist

Monica Merlin: How long did you spend with each person?

Cui Xiuwen: When I was testing them – to see if they had this ability to enter the spiritual realm – I told them, ‘If you go into this conceptual realm, a spiritual place where you lose yourself, then you can relax your body and follow your thoughts as far as you can. You don’t have to move, just do what feels most comfortable to you.’

Monica Merlin: So you did not have any rules for them.

Cui Xiuwen: No, I did not. One model was particularly great. When he came for the test, he was carrying a military bag. In China we would say he is er. Do you know this slang? It does not mean stupid, but a bit weird.

Monica Merlin: Yes, I think I know.

Cui Xiuwen: It is the character for the figure two. When he came to the interview, he had not even washed his face. He was totally dishevelled. One of his shoulders was higher than the other, and his legs were different lengths. If you saw him walking on the street, you would think he is like an animal or a piece of rubbish – you probably would not see him as a person. But when he got in the right state of mind for the test, you could see that he had a really strong spiritual ability, and quickly entered a realm of his own. It was a really big contrast.

Monica Merlin: As if he was completely detached from the outside world.

Cui Xiuwen: Previously it seemed he could only express himself as an outsider, but deep in his heart he had a close connection to the universe.

Monica Merlin: What does he do for a living?

Cui Xiuwen: He is a freelancer, doing odd jobs.

Monica Merlin: Was the space yours or did the model agency provide it?

Cui Xiuwen: I rented a studio.

Monica Merlin: I think that what was required of the models was really quite difficult, and scary. They were alone, naked, in an unfamiliar and empty space. It is great that the models had the ability to find that natural feeling in such a context.

Cui Xiuwen: Yes.

Monica Merlin: Where did you exhibit it?

Cui Xiuwen: It was shown at the Today Art Museum in Beijing. It was my major solo show. The walls were twelve metres high. Each character was four metres tall. It was spectacular. Twenty-two videos were played at the same time.

Monica Merlin: How long did each one last?

Cui Xiuwen: It depends. Each person needed a different amount of time to get into the right mental state. The shortest lasted about a minute before it was over. The model went into the state, but returned to reality only a minute later. There was another girl who, even if you called out to her to stop after fifteen minutes, would not be able to hear you – she had completely entered that state and could remain in it for half an hour. Everyone is different. Some people can only keep it up for a few minutes.

Monica Merlin: Was it quiet in the studio?

Cui Xiuwen: Sometimes it was quiet, other times there was some music.

Monica Merlin: Did anyone tell you what they were thinking about?

Cui Xiuwen: Some people did. Two or three kids from the series moved me and my colleagues so much that we cried; we were very touched by their experience. There was one teenage boy who was still in the early years of secondary school. He said that in that moment he felt like he was really helpless, and needed somebody’s love and care. He said he felt like he was growing wings like an angel. He did not speak when he was performing, but we could sense what he was feeling and it moved us to tears.

Later, we talked with him while we ate dinner. I was very affected by his performance, so I asked him, ‘What do you think art is?’ His answer at the time was ‘it is creativity’ or something like that, I forget. Then I asked, ‘How did you feel when you were being filmed?’ He said he felt that art was something sacred. He was innocent, and that was his genuine experience. I asked him some more questions, and his responses were very deep.

We also carried out some video interviews with some women after the shoot. They said they wished they could stay in that mental space and maintain the feeling they felt within it. They did not want to come back to reality because inside that space there was freedom.

Monica Merlin: What was in front of them when they were performing?

Cui Xiuwen: In front of them? They were on a stage, and there were lights on them. Actually the lighting blinded them so they could not see anything, even the people who were near the stage. I consulted with them and discussed whether or not they wanted to have a closed set with nobody there. Some of them wanted it, others did not. People are different. Some people said they did not mind. It did not need to be a closed set for them to enter that space, because when the lights were on, the space around them appeared dark.

Monica Merlin: So it felt like it was just them and no one else.

Cui Xiuwen: Yes.

Monica Merlin: Nowadays in China, can you normally exhibit art works if they involve nudity? I know that sometimes there are issues, for example, if the gallery or museum knows that there are nude performances, they won’t normally agree to it.

Cui Xiuwen: Sometimes there are restrictions. I had this problem when I exhibited at the Today Art Museum in 2010. At that time, the head of the gallery Zhang Zikang was very supportive. He let me go ahead with the exhibition, and said that if any problems arose the gallery would deal with them.

Monica Merlin: What do you think about the situation of women and women artists in China?

Cui Xiuwen: As I said before, China is, after all, still a developing country. It remains different from the other capitalist developed countries. China has its own specific historical background – thousands of years of traditional feudal culture, which has left us with a lot of customs surrounding the treatment and behaviour of women. There are many of them – for example, the notion of obeying the male in the family and the traditional female virtues.

Growing up in an environment that has remained consistent for such a long period of time, Chinese women have always hoped that they, like men, could face the world as independent subjects. It is not just a contemporary phenomenon – it existed in the past, too, but the method was different, as well as the context. A few decades ago, for people like yourself, China was just a remote possibility – you had not even heard Chinese voices, let alone knowing what they were talking about. But ten years later, with the development of the internet, everyone can understand each other through all kinds of technology. However, before new technology was introduced, people needed much more time. For example, Zheng He spent many years on his treasure voyages, finding foreign lands in order to communicate with different people and understand them better.

So for women in the Ming dynasty and earlier, how could they give voice to their own emotions, their minds, their spirit, or even their own ways of thinking? The method is different for every generation. When my generation was growing up, the history of women in China had an impact on us. For me, women from both Chinese and Western history had a formative influence on me. Yet, I think I was touched more by the independent thinking and consciousness of Western women, rather than the stories of traditional Chinese women.

When people are very young, they think about how they can become individuals and exist in this world, using their own language and having their own possibilities. When I was young, I had not yet thought about art – in fact, I would use whatever I could to express myself. I think I first remember having this independent consciousness in middle school or primary school, and it was around that time that I changed my name. My name was still pronounced Cui Xiuwen, but the characters were different. At that time, I thought that the characters for ‘xiuwen’ were pretty cheesy and mundane: ‘xiu’ meaning ‘beautiful’, and ‘wen’ meaning ‘culture’. They did not have a historical or cultural quality. That was the first time I did something for myself.

Monica Merlin: So you changed your name by yourself.

Cui Xiuwen: Yes, it was something I did by myself, but I did not know how to change my name. I said to my family that I wanted to do it, but everyone ignored me. So I had to figure out how to do it for myself. I looked in the dictionary to try to find different characters with the same pronunciation, because I still wanted it to sound the same. In the dictionary, I found the two other characters for ‘xiuwen’ – ‘xiu’ is a character meaning ‘mountain caves’, and ‘wen’ is one of the characters that make up the word ‘news ’. These two characters together make up a word – ‘the news that comes from mountain caves’. I thought it was mysterious, and it suited my unique and special personality. So I gave myself this name.

But when I was much younger, before I changed my name, the woman who inspired me was Wu Zetian. I learned about how she created entirely new Chinese characters, which is quite impressive. She was a true artist.

I have told you about my family and social background, for example how they ignored me when I told them about changing my name. It was as if they did not even hear me. So this was the only way I could change my name to one that I liked. This was the first time I managed to do something independently.

The second time came in the first year of middle school when I read about the Uprising of Chen Sheng and Wu Guang. One line in the story read: ‘swallows and sparrows cannot understand the ambitions of the swan’. At the time, that quotation inspired me a lot. If the brain is like a hard drive, then this information became engraved upon my hard drive. Compared to my classmates, I thought I was the swan. Do you understand the metaphor?

Monica Merlin: I think so.

Cui Xiuwen: It means, how can a small bird like a swallow or a sparrow know a large bird’s ambition? So I thought I was that large bird! I thought the people around me were all small birds, and they did not understand me at all. Actually, I never discussed what I was thinking with the people around me, but I always had a sort of intuition that the way I thought was different. I had this mindset when I was in middle school and I grew up believing I was different.

In high school I also thought I was different from others. All of my classmates in high school were dating, and that is the way they showed other people that they were different. One couple in my class was told off by the teachers, but they resisted by walking holding hands back and forth on the playground as if they were engaged in an act of performance art. Every day they strolled there to protest the school’s restrictions. But back then, according to my understanding, though their action was no doubt very daring, I thought something was missing. I was not very clear on what it was, but I was certain that it was not the way that I wanted to express myself.

In middle school, I started to draw relentlessly. I filled all the blank spaces in my school books with my drawings. This was the time that I started creating things. Actually, I did not understand what creating something meant, but I was expressing my own emotions, experiences and ideas. I cannot say my ideas back then were complete thoughts, but I expressed them nonetheless. I expressed myself in this manner until high school, until the second year, when I started studying drawing formally. My drawings always came out of a feeling that I had something I wanted to say. I decided to take the entrance exam for art school. There are a lot of stories, with twists and turns in the middle, but eventually I passed the exam.

Monica Merlin: What year was that?

Cui Xiuwen: It was 1988. In school, I was studying, but the desire to express my inner self is in my DNA – I have had it since I was little. At university I learnt certain skills, such as sketching, colour and design. Later, I realised it was not enough – these skills simply would not allow me to express myself.

After I graduated, I studied oil painting at the Central Academy of Fine Arts for two years. This experience changed me a lot. During those two years, I was able to take in a lot of information. Even though the academy is an institutional environment, the teachers and classmates still gave me things that the university did not – it was more substantial.

Then information also started to come from overseas. Foreign experts came to teach classes, and it became possible to buy foreign art books – even though they were extremely expensive. I remember the book I liked the most, which was on Giacometti, cost 900 yuan back then. I longed for it, and in the end I managed to buy it. But it was not just that one; we liked other monographs too. That was one way we learned. We did not have the chance to see any original works, so we had to rely on books and our teachers.

It is important to look at the academy teaching from a dialectic perspective. It was a platform to give you information, but the teaching system was not very rational. The teaching would not inspire you to think; it would tell you to find a master or an artist you like, get a copy of their monograph, and then copy it. In that kind of learning environment most people used the art books to copy and learn, and very quickly they were on a technical learning path. At that time, I had come into contact with philosophers, poets and some artists or scholars from abroad who were all strong thinkers. Their thinking had a profound effect on me. A small number of teachers at the academy were also strong thinkers and I was inspired by their lectures.

Monica Merlin: Is there anyone who had a particular impact on you?

Cui Xiuwen: At the academy, there was Yin Jinan, the current head of the School of Humanities at the China Central Academy of Fine Arts. His lectures were very inspiring. Also, the National Art Museum of China mounted a solo show of Alberto Giacometti, which I liked. That took place at the end of the 1980s and it moved me a lot. I think I’m inherently sensitive to different ways of thinking and to spiritual things; I can understand them well. When I went to see the Giacometti show at the National Art Museum of China, it was the first time that a work of art caused my hair to stand up, and I got goose bumps all over my body. It affected many people greatly. I think what I felt from Giacometti’s work was its spiritual power. Conversely, with Yin Jinan’s lectures, I felt that he was very scholarly. He taught from the perspective of a scholar and a thinker, which allowed me to think about new ideas and possibilities.

This year, I saw one of Joseph Beuys’s original works at the Central Academy of Fine Arts gallery. When I saw it, the work provoked many thoughts. These are the shows I saw in China, but I also saw shows by famous artists abroad. At that time, we all liked Balthus. When you see his original work, it is totally different from seeing it in books. The relationship between the reproductions in books and the original works is like the relationship between skin and bone marrow. They are very different.

When I went abroad and saw abstract art, it also had a big effect on me. I had studied it as part of my university course, including artists like Marcel Duchamp. At that time, I had not seen any of his work in person, only reproductions in books, which I looked at again and again. Duchamp has had a profound influence on Chinese artists, but even today I still think that his way of reasoning is so different from our own.

So, these people may provide you with ample context for my background and starting point as an artist. My earliest paintings were done within the teaching system of the academy – I found the artists I liked and copied their works. At that time I liked Max Beckmann, the expressionist artist. So I copied his works for a while. Then I realised that though we had some things in common, we were actually quite different. In those two years before I graduated, I started to think for myself and to use these reflections to interact with art, the world and life. In this process of reflection, I started to come into contact with Buddhism and philosophy.

But first I studied literature – I read a lot of literary books in high school and in university, including prize-winning books from Japan, as well as Chinese and Japanese novels. Also, I read some foreign critical essays. Apart from literature, philosophy also had an impact upon us. Everyone knew European philosophy books, and we had all read them, starting with Sigmund Freud at university, which was followed by Jean-Paul Sartre and Michel Foucault. Of course, there were plenty more, I won’t say all their names. But those were the most influential. After Foucault, I read Osho, the Indian philosopher.

Then I started reading about Buddhism. I started studying it extensively in 1990 and I am still studying it today. Of course Buddhism is based around the foundational scriptures, such as the Diamond Sutra, which I read. But I have also read books written by Buddhist abbots and monks.

So I have been deeply influenced by both Buddhism and philosophy. Philosophy came first, it taught me how to think about problems dialectically, and how to approach the world. Philosophy can give you two ways of looking at an issue, so you can approach a problem dialectically. But expressing yourself in art and in philosophy are different things. After I studied philosophy, I still thought that my expression was blocked, and I remained unable to express myself smoothly.

As my learning progressed, Buddhism became increasingly important. It was like I was walking in the dark and Buddhism suddenly opened a door for me and there was light. That felt great. However, when I felt good and kept going, I found that there was still darkness ahead. But one keeps moving forward, always in perpetual motion. In the end, I discovered that Buddhism actually teaches you how to apply literature, philosophy and also history – even though I have not studied much history – to your own life. You always open doors for yourself while looking at the future and moving forward.

In fact, it is about becoming conscious – a common word in Buddhism, also known as enlightenment. At first, people see things in a certain way, in this space. After one becomes conscious, one finds oneself in a different space. Actually it is a constant and slow process, and one becomes a little more aware each time. For any problem and question, if one is not conscious, it will be difficult to see clearly. Of course you [to Monica Merlin] are an Italian studying contemporary Chinese art, so you have a distance and will be able to see things more holistically. A lot of people don’t understand because they are inside whatever they are looking at. If one ever jumps out, it is one’s mind that jumps out – the body still stays there. So I think much of the time it is like this. I am on this level, and when I become more conscious I get to the next level and I have more to think about. I am always becoming more aware. It is like a pyramid and when you get to the top you can see everything below.

That is essentially my background; my educational background, as well as the background to my thinking and spiritual approach. There are many other aspects – for example, perceptions of and resistance to tradition. Even though China has so much history and culture, over the past 100 years lots of it has been broken off. So people of my generation are already separated from our history. In modern society, we have not kept many of the good things from our history. Instead, we maintain lots of the bad things and habits from the past.

After you one has realised that this is a problem, how can one solve it? How does one construct something complete? As individuals, people need to stand up in the world, and be able to stand firm. In order to do this, a complete structure is needed. This structure includes a knowledge structure – the knowledge one gains from study, one’s understanding of history and perceptions of society, as well as one’s feelings towards oneself, one’s mind, one’s spirit, one’s ways of thinking, and so on – all of the elements that mould a person. We all need a complete structure in order to really stand up.

But over the past 100 years in modern China, this has not been the case. My generation grew up naturally. It is like we were sheep put out to graze in the wild. There were so many children in our family that we could not be looked after properly. When I was young, my older brothers’ and sisters’ children were the same age as me, and my parents were busy raising children one after the other. They could rarely spend any time with me, so could not devote any time to teaching me. It was like being put out to graze, like being an animal.

We were incomplete, we did not have the things that were needed to become complete people. Our educational structures were also incomplete, so of course our value system was problematic. We grew up in this environment. We had to bring ourselves up, and at the same time deal with the outside world. It was not just a gender problem; women were not the only ones who suffered. We first needed to know how to become individuals – that was the first issue we needed to deal with. While doing this, of course gender issues came up, because they are part of the larger social system, but gender is only a facet of a larger problem, which needs to be solved first.

The deeper issue is human nature. This is the most basic question. It is this problem that still has not been completely dealt with. How can we solve this problem? Everyone is looking for a solution, but it is very difficult.

These questions are connected to my background and how I grew up. Although I have been creating art for many years, it is only now that I am able to stand up as a person. I have only just finished building this complete structure. I have only just achieved it now, even if I am not completely satisfied with it yet. I think I still have problems with human nature and gender to solve. I think that in the early years when I was creating art, gender was a major issue for me – it was the most pressing problem, because at that time, I did not understand; I thought that all problems derived from gender. But as I developed as a person, I realised that there are actually three problems: the first problem is human nature, the second is about standing up as a person, and the third is gender.

I think that at the moment, not just in China, but across the whole world, the best way to solve the problem of gender is to let people first stand up by themselves. As soon as you have stood up, at the minimum you will not be hurt and you can protect yourself. The so-called gender inequalities exist because women think it is unfair that they are always being hurt. They think it is a man’s world, and the woman’s world has been consumed and exploited. The only way women can avoid being consumed and exploited is to have a stronger spiritual and thinking structure than men. If you are a complete individual, then you will not get hurt. When she is a complete person and he is a complete person, then they can communicate equally. If a woman is not complete, then she will always be weaker than a man.

Why is there inequality? Chinese society has always given men more rights and opportunities than it has to women. This is a historical problem passed down from many years ago. In our early history, there were matriarchal tribes. At a surface level, gender seems simple, a matter of our flesh and bodies. But the relationship between men and women goes much deeper than this. So in my work, I am often trying to push a bit further into this relationship.

For me, the most important thing that art has given me is that it has made me more complete as a person. Nowadays, I think that art is just a way to make my life complete. I became complete because I chose art – or because art chose me. If I did something else, if I had not become an artist – or art had not chosen me – I think I could still have made my life complete. The result is the same; the method is chance. However, it is possible to achieve completeness just by thinking. In Buddhism this is the concept of panna indriya, but perhaps our faculty for understanding is not that strong.

Monica Merlin: You have clearly thought very deeply about these issues.

Cui Xiuwen: When you see my work, perhaps you will see that it changes in each period. It is always different. Why? When I was at the academy, I started thinking about spiritual matters, which played a big role in constructing my thinking structures. At the same time, this made me stronger, almost overnight. I became so strong that my ability to think and my thoughts developed faster than my skills. My thinking and my skills can work together, so I always change the way I express myself. If I did not have those thoughts or the spiritual ability to create this structure for myself, I think I would still be working on printmaking or oil paintings, stuck in a ‘technical phase’ that supplements one’s thoughts and one’s ability to express oneself. But I do not create in that way anymore. Now I use my thinking and all the technical forms to express my thoughts.

Monica Merlin interviewed Cui Xiuwen in her Beijing studio on 7 November 2013.

Published 20 March 2018