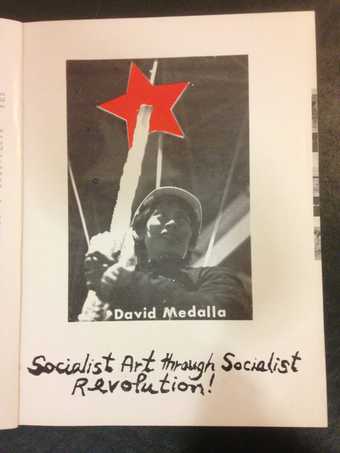

David Medalla

Socialist Art for Socialist Revolution

Photo-collage published in Art and Artists, January 1973

Fulfilling an urgent need to highlight art histories that have been previously side-lined by institutions, Eva Bentcheva’s paper explored the significant impact which Philippines-born artist David Medalla has had on the arts in the UK and internationally. Focusing on his participatory performance art produced between 1969 and 1977, Bentcheva’s paper argued that these artworks represent a unique ‘contact point’ between different artists, media and contexts, providing a nexus from which a deeper understanding can be gained of the critical discussions that have developed regarding art and social relations since the 1990s.

Bentcheva’s paper proposed that Medalla’s earlier experiences were crucial to the development of his politicised participatory art-making. In the 1960s, Medalla initiated various artistic innovations including: the Signals Art Gallery in London, which he co-created in 1964; the art newspaper, Signals News Bulletin, which he edited; and the artist commune Exploding Galaxy in East London where a number of collective interactive projects were produced, including The Bird Ballet (1967) and The Buddha Ballet (1968). This period also saw Medalla begin to express his political agenda via public performances, collaborating with American artist John Dugger on Chuang Tzu and the Butterfly Dream (1968), which was presented at the anti-Vietnam war gathering in Trafalgar Square. As Medalla established his artistic career in London and internationally via his nomadic projects, he would also present one of his boldest ‘performative protests’ back in the Philippines – a political demonstration at the inaugural launch of the Cultural Centre of the Philippines (CCP) in Manila in 1969. This performative gesture of protest against the dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos and the political ideologies that drove the construction of the CCP and its exclusion of artists like himself, also pushed the boundaries of political activism in his artistic practice. Bentcheva noted this performance as a landmark event in the development of Filipino modern art history – it was documented in a number of photographs and is still shared in the collective memory of the Filipino artistic scene as one of the first and bravest performance works in Philippines’ post-Second World War art history.

Open letter from David Medalla to Sir Norman Reid exhibited at Documenta 5, 1972

Tate Archive TGA 955/7/2/50

Bentcheva then narrated how Medalla continued to create several important works that combined political awareness with social engagement, developing the ’participation-production’ approach (a term Medalla coined to describe his approach of harnessing of ready-made and produced objects alongside more ‘conversational, interactive and participatory’ strategies in performance-making). For example, Medalla and Dugger formed the Artists Liberation Front in 1971, and participated in Documenta 5 in Germany the following year, constructing a pop-up pavilion entitled The People’s Participation Pavilion. Resembling a Southeast Asian traditional house and painted red to signify the socialist struggle in Vietnam, the project illustrated how the urban context was a site for participation and artistic engagement. Bentcheva highlighted this by describing how the Pavilion featured Dugger’s sonic installation and an environment in which visitors needed to remove their shoes to cross the troughs of water that encircled the structure in order to view the works on display, as well as Medalla’s iconic work A Stitch in Time 1967, accompanied by Medalla’s letter to the then incumbent director of the Tate in London criticising Tate’s decision not to acquire Bubble Machine in 1970. Bentcheva underscored how Medalla used the high profile platform of Documenta to situate this collaborative installation that brought together political and social engagement, and offered a sharp commentary on the invisible barriers in cultural institutions.

David Medalla with A Stitch in Time 1967 installed at another vacant space, Berlin, 2012

Photo © another vacant space

Bentcheva stressed that apart from overt political engagement, Medalla’s practice also harnessed aesthetic and poetic strategies for profound self-reflection. A Stitch in Time, which has had multiple successful iterations over the years across different venues, invites audiences to collectively sew symbols or objects onto a stretch of cloth. Medalla later explained during the Q&A, ‘When you’re stitching, people may be all around you, but your concentration is your own space. The moment you’re stitching, it is just you inside, no one else’.

Following Bentcheva’s analysis which demonstrated Medalla’s influence in different geographical locales and art histories, Medalla’s long-standing artistic collaborator, Adam Nankervis, shared his personal memories of David Medalla, ranging from their first meeting at the Chelsea Hotel in New York in 1990 to their shared love of poetry. Alongside the portfolio of participatory productions outlined by Bentcheva’s paper, Nankervis’ anecdotes also shed light on this other significant strand of Medalla’s performance art – improvisational happenings such as their explorations of the ‘impromptu’, which were enacted through ephemeral, public interventions that paid homage to various writers and depended on chance encounters while walking down Manhattan streets. In addition, Nankervis reflected on Medalla’s convivial personality and humane desire for connection; generous-spirited traits that drove the development of his collaborative practice.

A Stitch in Time, another vacant space, Berlin, 2012

Photo © another vacant space

As Medalla’s closest friend and collaborator on numerous performances – such as Shark Attack at the 1987 HIV awareness Act Up Movement, and the surrealism-inspired Mondrian Fan Club based on their shared admiration for Dutch painter Piet Mondrian’s paintings – Nankervis added unique insight into Medalla’s aesthetic approach, socio-political leanings and creative process. Through his personal memories, the fragments of images and notes he shared from the Notes for the Bird Ballet and the Exploding Galaxy projects were brought to life in his presentation. This insight places him appropriately in his role as manager of Medalla’s archive. As many of Medalla’s earlier performances were not or only partially documented, this archive’s materials are critical to ensuring Medalla’s legacy is recognised and preserved.

Nankervis’s presentation was followed by a performance by Medalla, so he concluded with a story that introduced the intervention. Nankervis shared how during a trip they took to the Philippines, a blind masseuse gave Nankervis a foot massage as he divined his future. Medalla then passed bags filled with pennies to the seminar audience. Depending on whether they called head or tails, visitors had to turn to their neighbour to either give or receive a foot massage. The intervention evoked a transformative sense of communality in the auditorium, connecting with Nankervis’ memory of Filipino community and culture, which reconfigured the immediate moment with a temporal/spatial slippage. During the Q&A that followed, the audience shared other memorable impressions of participating in Medalla’s art-making over the years, citing them as influential events and underlining again the timeliness of this seminar in reintroducing the narrative of Medalla’s significant contributions to our art history, and in particular, also continuing the Tate Research Centre: Asia’s critical refocusing of attention onto the significant additions of artistic practices from Asian and Southeast Asian artists in the UK and internationally.

Annie Jael Kwan is an independent curator, writer, researcher and producer based in London.