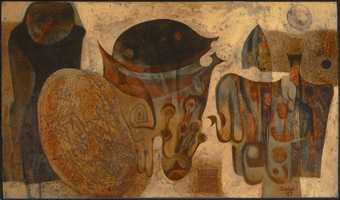

Ibrahim El-Salahi

Untitled (1967)

Tate

‘Textual Abstraction Within Transnational Modernism’ was held across two days, with Professor Sussan Babaie (Professor in the Arts of Islam and Iran, Courtauld Institute of Art) chairing the first part, with presentations by Professor Iftikhar Dadi, an associate professor at Cornell and a specialist in contemporary practices in South Asia, and Dr Fereshteh Daftari, a curator and scholar and expert on contemporary Iranian art. Nabila Abdel Nabi (Curator, International Art, Tate) chaired the second part of the event, hosting presentations by Professor Salah M. Hassan, a professor of African and African diaspora art at Cornell University, and Professor Nada Shabout, an art historian specialising in modern Iraqi art.

Screenshot from the online event ‘Textual Abstraction within Transnational Modernism’, with (clockwise from top left) Iftikhar Dadi, Sussan Babaie, Fereshteh Daftari

When discussions are anchored in the modern and contemporary, there is perhaps a hesitancy to delve too deeply into a ‘family tree’ of visual heritage – venerated genealogies of script and iconography – a path that can make interpretations of this material derivative or one dimensional. However, it is always important to negotiate how abstraction has been an enduring tradition within the historical trajectory of art from what has been traditionally labelled as those regions within or connected to the Islamic world, for want of a better term. It has been, at the same time, an influential strand of international modernism. When combined with calligraphy – viewed often as another shorthand for a practice deeply embedded within non-figurative traditions – textual abstraction has a certain power in its scope for ambiguity; words that are real or invented hold as much meaning as the artist allows – and more could have been made perhaps of this treatment of ‘the old’ through the lens of ‘the new’ and vice versa. To throw abstraction into the visual mix is to play with letters, words, even entire passages to the very limits of possibility; to obscure them, manipulate them and even sometimes to destroy them. To feed words further into the kaleidoscope of pattern and colour is to ruminate, meditate, deconstruct and obsess. Despite all this potential, however, the incorporation of script undeniably draws on a thread of common visual heritage. How to avoid, then, the triteness of artists ‘experimenting with tradition’ to create an art anew, while acknowledging the centrality of the Arabic script (including, but not limited to, Persian and Urdu), and particularly calligraphy, to the shared visual culture of these geographies?

Even when employed as an entirely unselfconscious or purely formal motif, script carries with it baggage that is historically and locally rooted. In a presentation titled ‘Script in Its Plural Manifestations’, Fereshteh Daftari termed this a ‘calligraphic DNA’, not set in stone but able to be corrupted, cloned and developed. There is not one set text, nor regulations on how it should be used. A particular point about the conflict between word and image brought to mind the work of the artists associated with the Saqqakhaneh School in 1950s and 1960s Iran, for example, in that there is a constant negotiation between expectations concerning an attachment to the hand of the practitioner, traditional processes of honouring, discipline and mastery, and passages written off the cuff about noodle soup and tea with sugar cubes that were inserted within the borders of abstract works on textile. Audiences are constantly faced with the dilemma of how to ‘read’ the text as it is situated within the context of the visual, an environment that may obscure layers of meaning and interpretation in the processes of the aestheticisation of text as much as it may enhance it. As described by Iftikhar Dadi in the talk titled ‘Calligraphic Abstraction’, an integration of figural elements often provided a tertiary level of interpretation – in being never quite definitive – with passages envisaged as written in blood being the most self-referential and restless connection with words, as artists such as Seyed Sadequain composed their own poetry alongside their works.

The joint chairs provided a rich contextualisation of the broad and ever-active conversation surrounding the role of script, calligraphy and text in contemporary art from the Middle East, North Africa, West Asia and South Asia and their diasporas. In bringing scholars and curators together with a global online audience, the two discussions allowed for expert analysis of key movements and artists associated with textual abstraction (including Anwar Shemza, Dia al-Azzawi, Shakir Hassan Al Said, Parviz Tanavoli and Ibrahim el-Salahi, to name a few) and an interrogation of deeply nuanced responses to the interrelated frameworks of decolonisation, heritage, religion, national independence and identity.

Screenshot from the online event ‘Textual Abstraction within Transnational Modernism’, with (clockwise from top left) Nada Shabout, Nabila Abdel Nabi, Salah Hassan

Throughout the two days, text emerged as a typographical exercise both formally and conceptually. This was particularly evident in questions surrounding the use and taxonomy of region-specific movements, particularly hurufiyya and Saqqakhaneh. Central to this was the position of mystic and religious associations of particular words and letterforms and how this operates in the discourse of contemporary art. Hurufiyya, for example, is a highly contested term in its application to modern Arab art given its association with medieval esoteric Sufi thought as well as a formal purity of abstraction. In Wijdan Ali’s Modern Islamic Art (1997), for example, a line was drawn between hurufiyya, calligraphic abstraction and a specifically Islamic continuity. Nada Shabout, however, when explaining alternative applications of the term, emphasised a ‘disconnect from the word calligraphic’ itself, citing the difference in the disciplines of traditional calligraphic art and the principles of hurufiyya as a modern art movement in which letterform became sign. ‘They spoke of the Arabic letter in one dimension’, she said in her talk ‘Al Harf: A Performative Site of Becoming in Iraqi Art’, referencing the 1971 manifesto of the Al Bu’d al Wahad (the One Dimension Group) where artist Shakir Hassan Al Said (1925–2004) spoke of ‘an extension of the past to the time before the existence of pictorial surface; to the non-surface’.1 Even connections with lettrisme as a European counterpart are somewhat misleading, given not only collapsing the historical specificities of both hurufiyya and the surrealistic, French avant-garde philosophy but also their attachments to the signification of text, the meaning of art itself and, by extension, abstraction as a visual mode.

The closing remarks of Dr Daftari concerning the misunderstanding of script as a decorative commodity brought to mind the words of Iranian contemporary artist Barbad Golshiri, who commented on the apparent devaluing of the Persian script in light of commercial interests: ‘The art market’, he says, ‘is limiting Persian writing to formalist, harmless and exotic calligraphy made for those who cannot read it.’2 The tension between the formal appeal of the fluid undulations of Arabic letterforms, however illegible to eyes that do not recognise their meaning, can provide a seductively effortless modernism that easily speaks to the cosmopolitan desires of collectors and institutions; the absence of iconographic signifiers can be so compelling as evidence for a ‘universal’ mode of understanding that gets quite literally lost in translation, with not much actually being understood at all. In other words, this is part of the evidence of major institutions ‘scrambling to catch up’, in the words of Salah M. Hassan, with an area of scholarship that is itself dealing with issues of its relative newness and a unique volatility that has been invariably shaped by fraught geopolitical contexts.

A collective conclusion was proposed that we are at a juncture, or a moment of crisis, stuck between creative output and its public and professional reception. As such, these discussions allowed for a reappraisal of the treatment of this material by art historians, critics, local authorities and contemporary audiences. The flaws and limitations of archival access; dedicated publications; exhibitions, biennials, collections and museums; regional conservatism and the perennial disconnect between art and ideas flowing from East to West and vice versa were all taken to task as much as they were acknowledged as part of the tricky narrative of modern art within transnational and post-colonial contexts.