Marwan Rechmaoui

Beirut Caoutchouc (2004–8)

Tate

The background for the opening slide of the symposium showed a fraction of the Lebanese artist Marwan Rechmaoui’s Beirut Caoutchouc 2004–8, a large floor-based map of Beirut made of slabs of black rubber over which visitors are invited to walk. Part sculpture, part cartography and part landscape, the work both summons and synthesises many of the concerns of this one-day event, namely how the reflection upon and representation of urban space, particularly through the visual arts and photography, have contributed to and intervened in the making of place and identity. ‘Temporary Spaces’ looked at the entanglement between the urban and social dynamics of a number of cities in South Asia and the Gulf, through the viewpoint of the work developed by a selection of key artists, architects, photographers and scholars. The diverse sequence of speakers and presentations gave valuable insights to the overall discussion and created a cohesive, engaging event.

Despite this, the proceedings displayed a significant omission or oversight that must be mentioned here. The title of the symposium references the 2017 book Temporary People by Deepak Unnikrishnan, a novel that engages with the contemporary presence of migrant labourers in the UAE and the conditions of marginalisation and precarity to which they are subject. The kafala (visa-sponsorship) system that operates in the region allows employers to exploit and abuse workers with little legal recourse, such that many consider it a form of slave labour.1 Workers bonded in the kafala system work primarily in the domestic and construction sectors and without them the rapid and large-scale expansion of cities like Dubai would not be possible. However, despite the allusion to these contexts in the symposium’s title and despite it being held in Dubai, issues around exploitative migrant labour systems were not addressed in the event. Indeed, it became evident that a number of topics – including the exploitation of migrant labourers and the effects of the oil-dependent economies on climate change – were avoided, most likely due to the impossibility of contributors addressing such issues in a country where criticism of authority often leads to imprisonment or disappearance.2 These omissions and the reasons behind them remained unacknowledged throughout.

The opening panel, ‘Temporal Traces and Translocal Exchanges’, chaired by Devika Singh, Curator of International Art at Tate, explored the entanglement between personal memory and national identity through the lens of a built environment shaped by translocal practices. The presentations hinted at a struggle with modern heritage in countries such as the UAE and Kuwait, while pointing to ways in which architectural, curatorial and artistic methodologies can intervene in the understanding of history, and provide new ways of dealing with such heritage today.

Michele Bambling presented on the project Lest We Forget: Structures of Memory in the United Arab Emirates, which she curated for the UAE’s pavilion at the fourteenth Venice Architecture Biennale (2014). The project investigated how architecture from the 1970s and 1980s, built within a rapidly expanding urban context, moulded the newly established federation and laid the foundations for its emergence on a global stage. Due to the lack of readily accessible information on the building programmes, Bambling adopted a methodology that combined professional architectural records with personal documentation, including Emirati family photo albums and postcards. The pavilion expanded traditional notions of archive and heritage, connecting the ‘history’ of official documents with the highly personal narratives and lived experience recorded in private photographs.

Bambling’s investigation brought to my mind Kuwait’s contribution to the same Architecture Biennale, titled Acquiring Modernity and curated by artist Alia Farid. The project investigated a number of buildings commissioned by the state as ‘modern symbols of status and progress’ to explore how Kuwait dealt with modernity, with a special focus on the Kuwait National Museum, designed by French architect Michael Ecochard in 1960. Acquiring Modernity transcended the Biennale both in time and space, with one of the modernist buildings that had fallen into disuse serving as a temporary research centre. This occupation not only brought life to the abandoned construction but also underlined how modern buildings have been disregarded. Indeed, in the 1950s and 1960s Kuwaitis brought many architects from abroad to construct their new cityscape. It is often argued that because these buildings were designed by ‘foreigners’, there is a tendency to underestimate their cultural value, which in turn validates the neglect and disregard of these unique constructions.

Counteracting this general idea, architect Ricardo Camacho’s presentation went beyond the impression of the Pan-Arab region being a passive receiver of what Camacho calls an ‘imported modernism’. He elaborated on the urban modernisation of Kuwait in the decades following the 1960 establishment of OPEC (Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries), and in Dubai today. His analyses focused on the architecture practice Pan-Arab Consulting Engineers, where architects and engineers balanced their Arab identity, international training and connections with foreign firms.

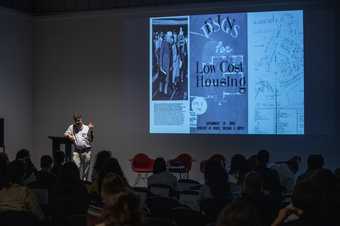

Rohan Shivkumar presenting ‘Nostalgia for the Future: A Meditation on Indian Citizenship, Modernity and the Architecture of the Home’ as part of ‘Temporary Spaces’ at the Alserkal Arts Foundation Project Space in Dubai on 1 November 2019

© Augustine Paredes

Architect and filmmaker Rohan Shivkumar further expanded on the relationship between architecture, civic identity and nation-building through the film Nostalgia for the Future, which he co-directed with Avijit Mukul Kishore. The film investigates the idea of the body of the citizen, the nation and the home in modern India via the histories of four key buildings: the Lukhshmi Vilas Palace in Baroda; the Villa Shodhan, designed by Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier; the Sabarmati Ashram, which epitomised the Gandhian aspirations of the nation-state; and the public housing designed by the Government of India. Shivkumar used these structures to talk about the idealised bodies that were meant to inhabit them. The ‘prosthetic’, ‘naked’, ‘sinful’ and ‘machine’ bodies were conceptualised against a wider strategy of Indian nation-building through architecture, propaganda film, and the built environment. By placing the citizen’s body at the core of his argument, Shivkumar’s film relates to Bambling’s curatorial approach in Lest We Forget, which brought to the fore the way citizens constructed their self-image in relation to their built environment.

Strategies for the representation of the relationship between citizens and their urban contexts were further explored in the second panel, ‘Mapping the City’, chaired by Nabila Abdel Nabi, Curator of International Art at Tate. The panel showcased photographic and artistic practices that re-shape traditional notions of documentation, cartography and testimony as a means to promote critical debate on social and urban issues.

Architectural photographers Randhir Singh and Mohamed Somji reflected upon the role of photography in presenting alternative narratives to modernist canons and in rescuing the criticality of contemporary image production. Singh presented his photographic series Water Towers 2012–16 and CPWD (Central Public Works Department) 2017 in which he captures infrastructural architectures and government-housing colonies in Delhi. By redirecting the gaze to these overlooked buildings and unearthing the spaces and stories within them, Singh subtly problematises concepts such as socialism, governmental control and national identity. Somji presented a series of works from artists and photographers around the Gulf that stretch conventional notions of documentary photography. These included Maryam and Hussain AlMoosawi’s photographic exploration of Juffair, which Somji described as ‘the Las Vegas of Bahrain’; Hala Al Ani’s Typology of Houses 2010, which records Dubai’s numerous imitations of architecture styles; and Roger Mokbel’s series Describe the Sky to Me 2018 on the Yerevan Bridge in Bourj Hammoud, Lebanon, one of the most densely populated areas in the Middle East.

The contributions from artists Nazgol Ansarinia and Marwan Rechmaoui further complicated notions of documenting and representing urban realities. Working with a variety of media and exploring the intense urban and social transformations that are evident throughout the cities of Tehran and Beirut respectively, both artists develop multi-layered pieces that evade easy categorisation and mobilise both body and mind towards a critical understanding of the social and spatial dynamics around them. Iranian artist Ansarinia presented a series of works that reflect upon tensions between private worlds and the wider socioeconomic space through the constant demolishing and rebuilding of Tehran’s urban landscape. Rechmaoui presented his work Blazon 2015, which presents the interrelations between the urban, social, political and historical fabric of Beirut with a game-like structure in which every neighbourhood represents an armed battalion with its own set of attributes.

The third and final panel, ‘Negotiations in and Beyond The City’, chaired by curator Maya Allison of the New York University Abu Dhabi, explored entry-points for alternatives to the contemporary rhetoric of technocratic, market-driven city-making and endless urban growth. These included natural resources, extreme weather phenomena, the liquidity of global finance, and social networks, all of which could be seen as ‘common grounds’ beyond national boundaries and cultures.

Aerial image of Hidd, Bahrain, showing a number of fish traps c.1951

© Royal Air Force

Architect Ali Karimi presented Civil Architecture’s projects for the Kuwait Pavilion in the fifteenth Venice Architecture Biennale (2016) and the 2019 Oslo Architecture Triennial. Both propose new ways of understanding the Gulf beyond national borders and through an emphasis on natural features and resources as possibilities for reconciliation rather than separation. Presented at the Oslo Triennial, Two Thousand Years of Non-Urban History revises the history of the Gulf through the analyses of three cases of ‘non-urban planning’: the ‘desert kites’, large hunting infrastructures constructed over generations, are an example of a semi-nomadic semi-agricultural strategy for trapping migratory herds; the ‘fish traps’, small-scale architectures that still provide a model for community-centred food security;3 and the ‘springs’, water channels and underground infrastructure. These vernacular structures reveal a deep understanding of the territory and its resources and make evident the communal and formal aspects that allowed for pre-oil growth in the region.

The connection with territory and natural resources permeated the presentation of curator Tausif Noor, which looked at climate change and its future effects on urban and environmental planning in South Asian cities. The curator presented the environment as a shifting actor in its own right, and proposed artistic interventions and liquidity as a conceptual organising principle for urban planning, further supporting this argument by showing the practices of artists Sheba Chhachhi, Vibha Galhotra, Mathur/Da Cunha, and others. Noor’s presentation was complemented by the first-person account of artist Abdul Halik Azeez, who talked about his experience in portraying the daily life of Colombo, Sri Lanka. Since the end of the civil war in 2009, he observed how Colombo had been captivated by the idea of becoming a ‘world class city’. Through his quotidian photography and social media activity, Azeez captures and disseminates mundane situations, instances of violence and evictions, using his images to invite discussion with a broad audience online.

The contributors to the ‘Temporary Spaces’ symposium at the Alserkal Arts Foundation Project Space in Dubai on 1 November 2019

© Augustine Paredes

Concluding remarks from curator Maya Alison brought to the fore some of the questions that permeated the symposium, namely a balance between two impetuses: on the one hand, the sense of urgency that motivates these practices, and the necessity to finding solutions for actual problems; on the other, the need to ask paradigm shifting questions, to nurture complexity and opacity, and to deal with discomfort rather than reassurance. The symposium was successful in gathering practices that, despite being distinct in their approaches, have meaningful connections with one another. The chain of presentations provided a valuable overview of the many urban and social dynamics that cities in the Gulf and South Asia are going through. Perhaps more valuably, they also presented a number of possibilities and strategies for tackling the interlinked socio-political, techno-economic and environmental crises of today. Nevertheless, the fact that the symposium was held in the UAE led to the omission of crucial issues, meaning that the possibilities of moving towards a critical and sustainable production of contemporary urban space could not be fully explored. Organisers of such events have a responsibility to interrogate the socio-political context in which they are held. In this case, the valuable contributions of the attendees appear to have been made in spite of the context, which acted to exclude key discourses and suppress discussion, denying even the acknowledgement of what was omitted.