The panel discussion which formed part of the event ‘Chile 73 – Panel Discussion and Screening’ at Tate Modern, 22 February 2020

Photo: Guillaume Valli © Tate

The Chilean military coup d’état of 11 September 1973 unseated the democratically elected socialist government of Salvador Allende. Led by Augusto Pinochet, the resulting junta began an authoritarian project of massive social, economic and political change which lasted until the country’s transition back to democracy in 1990. Accompanying the display, the event ‘Chile 73 – Panel Discussion and Screening’ brought together four speakers and a documentary film with the aim of opening up discussion on the period of the Chilean dictatorship, its effects on the art and culture of the time and its continuing influence today. Further to this, as asserted by curator Michael Wellen at its outset, a central aim of the event was to show how art and ideas can move independently of borders by drawing on histories of transnational solidarity networks.

Left to right: Roberta Bacic, Claudia Zaldivár, Alexia Tala and Lynn MacRitchie giving presentations as part of ‘Chile 73 – Panel Discussion and Screening’ at Tate Modern, 22 February 2020

Photo: Guillaume Valli © Tate

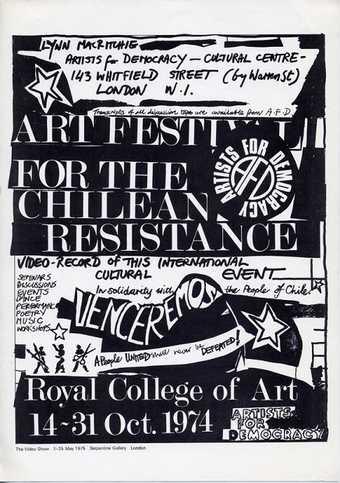

The event began with short presentations from each of the participants. Lynn MacRitchie, an artist and writer, spoke on her involvement with the Arts Festival for Democracy in Chile, held in London in 1974, which aimed to show solidarity with those suffering in Chile and fundraise through the sale of artworks. Claudia Zaldívar, Director of the Museo de la Solidaridad Salvador Allende (MSSA), presented on the museum’s transformation since its inception in 1971 and its adaptive role in times of social crisis. Roberta Bacic, a curator of conflict textiles, spoke about arpilleras – brightly coloured patchworks, often with explicitly political subject matter – as works of testimony, resistance and empowerment. Alexia Tala, Chief Curator of the 22nd Paiz Art Biennial, Guatemala, drew on three years of work with the artist Lotty Rosenfeld in preparation for a forthcoming publication to discuss how the artist was responsive to the political situation and contextualised her practice within the cultural and artistic scenes of Chile and Latin America. Patricio Guzmán’s The Battle of Chile (Part 2): The Coup D’Etat (1976), which was screened at the end of the event, closely studied the political developments immediately preceding the coup d’état.

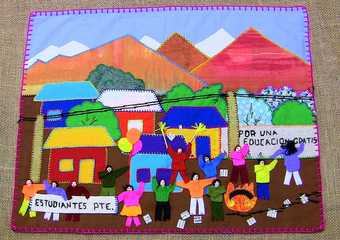

Aurora Ortiz

Chilean Students’ Strike 2011

Paro de los estudiantes chilenos

Conflict Textiles Collection, Northern Ireland

© Aurora Ortiz

Photo: Rory McCarron

One theme to emerge was the idea of artists being important bearers of testimony during the dictatorship. Answering a question from the audience on the effectiveness of resistance art in achieving political change, Tala voiced the idea that, more than achieving change, taking on resistant narratives comes out of a need to express that resistance and give form to experience. Bacic, looking at it most directly, showed this in her presentation in relation to the unknown artists of the arpilleras. She underscored the value of testimony not simply as a record of lived experience, but as a generative tool. Made in workshops run by the Catholic Church, the patchworks (which she termed the ‘photography of poverty’) often grappled with disappearances or government repression and were sold overseas in order to raise both money and awareness of the conditions in Chile. Bacic focused on how the medium allowed the creators to communicate in an entirely new and immediate language which continues to have relevance today. Bacic gave the example of artist Aurora Ortiz who uses the arpillera to engage with contemporary political situations such as the ongoing struggle for recovery of land by the indigenous Mapuche population in south-central Chile or the Chilean student protests of 2011–13.

Lotty Rosenfeld

Still from the film A Mile of Crosses on the Pavement 1979–80

Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid

© Lotty Rosenfeld

Tala’s presentation on Rosenfeld’s work also echoed the idea of testimony, this time in the artist’s documentation of her actions and interventions in urban spaces. Tala quoted Rosenfeld as saying: ‘Given the context that was ravaging my country, it became essential for me to rethink my role as an artist and visually seek other ways of expression’. One of these ways was to take up film alongside photography so that she could document art actions and public displays of dissent. Tala gave the iconic example of A Mile of Crosses on the Pavement 1979–80, in which the artist adhered white tape perpendicular to the centre lines in the Calle los Militares, a street in the country’s capital city, Santiago. The crosses formed by the lines and the tape were a direct interference by the artist in a public symbol of control and spoke to the disruption of the society’s social fabric. Rosenfeld emphasised the importance of recording such actions, with the film and photographs long outliving the tape on the road. Tala also looked at Rosenfeld’s later work, made after Chile’s return to democracy, and how similar tools were used by the artist to comment on contemporary issues. Tala gave the example of Rosenfeld’s video work La Guerra de Arauco 2001, which again looks at the land rights of indigenous Mapuche people.

Addressing a central aim of the day – to look at transnational solidarity networks that grew out of the events in Chile in 1973 – Lynn MacRitchie’s talk gave context to how one such network manifested in London. The Arts Festival for Democracy in Chile included an exhibition of 300 donated artworks and two weeks of talks and performances, held at the Royal College of Art on 14–30 October 1974. As a member of Artists for Democracy, MacRitchie worked with the founders – David Medalla, Cecilia Vicuña, John Dugger and Guy Brett – to organise the festival and used a borrowed film camera to document it. She looked at how disparate groups from London’s art and activism scenes coalesced around the event. For the artists involved, MacRitchie said, it provided a space for discussion, ‘to question how they made work and how their art related to politics’, although she did not elaborate on the results of these questions. MacRitchie was the only artist on the panel and it would have been valuable to hear if the festival had ongoing influence on her work. Although perhaps not possible in the time allotted, the discussion could have also been expanded by better contextualising the intentions of the festival and its impact, and by bringing more criticality to the meaning of ‘solidarity’ to those involved.

It was in Zaldívar’s presentation that a concrete idea of solidarity and its meaning in an artistic context emerged most clearly. Following the coup d’état, the Museum of Solidarity became the Salvador Allende International Museum of Resistance (Museo de la Solidaridad Salvador Allende – MSSA) and between 1975 and 1990 moved into exile, travelling widely across Europe and Latin America. During this time, it showed artwork donated to the collection from around the world as a gesture of resistance. Exile forced the museum to seek new strategies and to rethink the idea of solidarity in relation to the institution, becoming, as Zaldívar described it in her presentation, a decentralised network that ‘from art wanted to make visible an active opposition to the Chilean military regime and denounce the violation of human rights’. Today, Zaldívar continued, the MSSA maintains this adaptive quality at its permanent site in Santiago, as ‘a museum that breathes’. She gave the example of the most recent protests in Chile: when most other institutions were forced to close, the MSSA responded by making the museum’s building a hub in which talks and workshops were held on issues being protested including inequality, neoliberal economic policy and the 1980 constitution of dictator Augusto Pinochet.

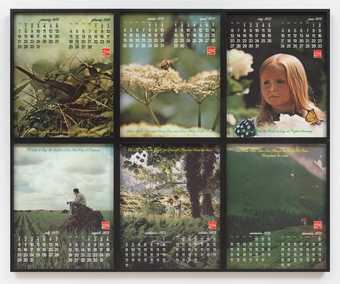

Alfredo Jaar

September 11, 1973 (Coke) 1982

Collection of the artist

© Alfredo Jaar

Indeed, it seems a resonant moment from which to look back at this period, with social unrest in Chile erupting in mass protests in late 2019 and continuing into 2020, many of which were focused on the neoliberal economic policy introduced during Pinochet’s dictatorship. As a result, a historic referendum on the constitution was to due be held in April 2020, but has since been delayed until October due to the Covid-19 pandemic. The event’s timing was touched on in the introduction by Michael Wellen, Curator of International Art at Tate, who was one of the curators of the A Year in Art: 1973 display. Wellen showed two recent social media posts and drew parallels with the visual language of a seminal work by Alfredo Jaar included in the display. Jaar’s September 11, 1973 (Coke) 1982 shows the day of the coup repeating itself on a calendar; the two Instagram posts showed the 18 and 19 October 2019, days of significant clashes between riot police and protestors in Santiago, repeating themselves in the same way. However, despite brief references to the events in Chile today by Wellen, Tala and Zaldívar, and Bacic looking at the enduring relevance of arpilleras, more time could have been given to the ways in which art is now being used as a form of protest and how we handle times of uncertainty in the present moment. A useful avenue of further consideration could also be how transnational solidarity networks look to us today, reflective of changes in the ways we communicate or access information.

At the close of the day it seemed that perhaps time for these discussions could have been allocated in place of screening Guzmán’s film. The Battle of Chile (Part 2): The Coup D’Etat chronicles the events leading up to the coup, using first-hand footage and newsreel from protests, workers meetings and interviews with Allende supporters. It gives a contemporary account of the complex political and social situation in the nine months before the coup and is known as a pioneering film of the documentary genre, made by Guzmán while in exile. As a resource it undoubtedly gives greater and necessary background to the political situation that was addressed by the speakers throughout the day. However, as it was separated from the body of the event, it was unable to feed into the discussions at hand.

The panel discussion which formed part of the event ‘Chile 73 – Panel Discussion and Screening’ at Tate Modern, 22 February 2020

Photo: Guillaume Valli © Tate

Individually, the presentations gave insights into institutions, artists and modes of making and dissemination that were responsive to the political and social environment in Chile. Compelling threads emerged, particularly around ideas of testimony and solidarity. As an art historian working with this subject, one often sees exhibitions that show a simple narrative championing well known figures and leaving unseen the many and varied networks of artists that continued to work in Chile during the dictatorship. The event showed the potential to complicate these narratives, even where it is not possible in a small display. Perhaps, however, even more attention could have been paid to the breadth of artistic response outside of the making of arpilleras and widely known figures, such as Rosenfeld, Jaar and Carlos Leppe who, while no doubt important, are often the sole focus of such displays. In the interest of time and to allow for questions to be taken from the audience, the planned panel discussion was unfortunately cut short, and not guided at its outset. This part of the event could have been an opportunity to develop a deeper discussion between the participants where they might have fleshed out, complicated or found intersections between their subjects and arguments. The event, however, successfully expanded on the subject addressed in A Year in Art: 1973 and brought together a panel of speakers that was engaging and delivered on their subjects with a clear depth of knowledge, warmth and unique insight.