In a highly acclaimed article published in the Winter 1991 volume of Critical Inquiry, the cultural theorist Kwame Anthony Appiah posed a critical question for the present and future of postcolonial studies: ‘Is the Post- in Postmodernism the Post- in Postcolonial?’. Appiah maintained that the prefix ‘post’ in postmodernism and postcolonial both signal a space-clearing gesture, a movement against what had come before – modernism and its subscription to reason; and the colonial condition that haunted newly independent African nations. And yet, he argued, ‘postcoloniality’ has in fact been the condition of only a comprador intelligentsia, a comparatively small, Westernised political body of writers and thinkers whose role in the trade of cultural commodities in worldwide markets allows them to invent an Africa ‘for the world, for each other, and for Africa’.1 What then is postcoloniality for the rest of us? What does postcoloniality mean for those excluded from the polarised flow of capital, recognition, and power between the West and its former colonies.

Indeed, as the organisers of ‘From Alexandria to Tokyo: Art, Colonialism and Entangled Histories’ pointed out in the symposium literature and discussions, the hierarchical relation between the center and peripheries of global politics – the so-called binary of the West versus the rest – has often characterised debates on artistic production and colonisation, bypassing other currents of influence and practice. Appiah argued that this process fails to account for the cornucopia of artworks and ways of life that exist outside this dichotomy and its definition of coloniality. Such artworks throw us into a whirlwind of reflections on who we are and how we make sense of the multitude of colonial histories that created us, as opposed to the one grand History of Western colonialism. ‘From Alexandria to Tokyo’ brought Appiah’s provocation to life. The presenters unpacked the many hierarchical structures that gave rise to non-European forms of domination within the Global South which, without careful examination, risk permanent erasure today in the name of nationalist unity and the challenges of the Covid-19 era. The symposium moved through themes of transnationality and identity formation, with a special nod to the Cold War period, and arrived at a radical re-envisioning of postcoloniality and neocolonial practices in Asia. As such, the scholars and artists who took part realigned the current debates on art and colonialism towards a broader understanding of non-European colonial relationalities and their continuation into the so-called ‘postcolonial age’.

Clockwise from top left: Devika Singh, Fusako Innami, Helena Čapková and Sanathanan Thamotharampillai during the panel discussion ’Between Nationalism and Cosmopolitanism‘, part of ’From Alexandria to Tokyo: Art, Colonialism and Entangled Histories‘, 3 December 2020

The concept of transnationality as a social practice that operated both within and outside the sphere of Western colonisation, yielding unexpected collaborations and repercussions far beyond any particular national border, provided a critical point of departure for several contributors. Fusako Innami opened the symposium with her presentation ‘Sensory Topography: Bodies, Artist Networks, and the Interwar Ballet Russes’ in which she foregrounded the social practice of embodiment. Embodiment as reflected in the life and work of Japanese dancer Komaki Masahide, she argued, entailed the continuous participation of the artist in cross-cultural collaborative networks beyond his or her own nation. In this framing, embodiment becomes a vehicle for rewriting existing nationalist topographies through sensory experiences. Drawing from Marxist theorist David Harvey’s conceptualisation of the meaning-making potential of bodily occupation of space and time, Innami’s talk highlighted the way transnational mobility and artistic networks can reconfigure the relationship between topography and what sociologist Marcel Mauss called ‘techniques of the body’.2 As a Japanese dancer in China, Komaki was a literal embodiment of the colonial expansion of empires. Innami argued that he exemplified ‘how individual bodies may function as part of a larger political and cultural propaganda while developing a career’. And yet, this process by which an individual body takes up space in a surrounding environment also allows the individual body to be affected by individual action, movement and mobility that can reshape, and thus ‘deterritorialise’ social boundaries themselves.

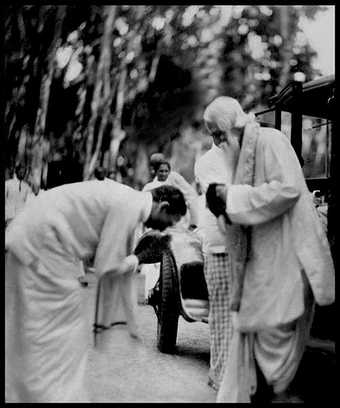

This form of ‘deterritorialisation’ repeated itself in the case studies presented by Helena Čapková in her presentation on traditional Japanese crafts. She described how, through the use of craft, the French painter Mirra Richard, later known as the Mother of Pondicherry, also managed to tap into her transnational experience in Japan to introduce Japanese craft into the ashram space of South India, with an artistic, even strategic or political, intent. Here too, individual bodies functioned as sites of embodied history, ideologies, and knowledge that upended the supremacy of the nationalist project and deterritorialised the meaning of the space they occupied. The operation of transnational hubs enabled the exchange of methods and ideas, as well as the opportunities for anti-colonial insights and intelligence. That such sharing could occur outside the paradigm of Western colonialism proved decisive in the formation of modernist subjectivity in the Global South. In the case of Sri Lanka, Sanathanan Thamotharampillai noted in his presentation that the birth of modernist Sri Lankan artforms was marked by a creative and political tension between competing currents: Western, Victorian academicism on the one hand; and Indian intellectualism on the other. Indeed, against the backdrop of heavy Victorian influence, the historical visits of the poet Rabindranath Tagore to this island nation, Thamotharampillai contended, played an vital role in the creation of modernist art groups such as the celebrated 43 Group.

Rabindranath Tagore (right) being greeted by Wilmot A Perera (left) on his arrival in Sri Lanka, 20 May 1934

The tug-of-war between European and non-European forms of hierarchical relations compelled many newly independent nations to negotiate a host of nationalist and cosmopolitan attitudes, a situation exacerbated by the onset of the Cold War. A number of presentations picked up on this thread and zoomed in on the rise of Soviet socialist internationalism, a transnational politico-cultural project which shared notable similarities with China’s Belt and Road initiative, begun in 2013.3 Examining the work of Egyptian artists Hamed Owais, Inji Efflatoun and Gama El Sagini, Maria Mileeva argued in her presentation that ‘the Soviet perspective offers a novel vantage point from which to consider the relationship between decolonisation and socialist internationalism as a determining factor in constructing new visual systems of representation in the post-war period’. Soviet social internationalism provided newly liberated states in North Africa with a compelling alternative to Western modernism, capitalism, and imperialism. This process drove new national art and artistic identities to take hold. The Soviet’s claim to anti-imperialism, however, was contradictory at best since it failed to reckon with the USSR’s own colonial project of ‘Russification’. In his contribution to the symposium, artist Zeigam Azizov traced the beginnings of Russification back to the time of the Russian Empire. As many scholars have discussed elsewhere, Craig Campbell being a notable example, the mantra of Russification continued well into the era of socialist construction and later, sovietisation.4 Considering the context of the Cold War, it was no surprise that many aspiring global powers embarked upon the same diplomatic endeavours in politics, art and culture, although often to conflicting ends. For example, the Republic of China’s projects of military interventionism and cultural exchange in the Global South proved troubled from the start, something Nobuo Takamori aptly summed up in the title of his presentation – ‘The Impossible Empire’.

Nadia Radwan discussing the work of Egpytian artist Inji Efflatoun in her presentation ‘Shifting Art Constellations and the Non-Aligned Movement in Egypt’, part of ’From Alexandria to Tokyo: Art, Colonialism and Entangled Histories‘, 3 December 2020

However, in the aftermath of the Bandung Conference, held in Indonesia in 1955, the global circulation of concurrent ideologies and aesthetic movements presented new independent nations with the challenge of navigating complex networks of alliances.5 For example, as Nadia Radwan outlined in her presentation, the nonaligned movement in Egypt sparked a number of political and artistic responses, a set of novel ‘geographies of power’ that spanned across the Mediterranean, Pan-Arabist, Pan-Asianist and Pan-Africanist networks. These developments, alongside the institutionalisation of art as evidenced by the organisation of events like the Alexandria Biennale, enabled new metaphors for anti-colonial discourses, hybridised identities and artistic liberation, though not without limitations. This kaleidoscopic interface of power, ideology and art mirrored similar developments elsewhere. In Cambodia during the 1960s, for example, the organisation of international expositions symbolised not only the Sangkum government’s project of cultural diplomacy but also its efforts in maintaining an impossible politics of neutrality during the decades of the Vietnam War, also known as the American War. Postcoloniality in the Cambodian case was plagued by continuous violence, dissolution of multiple regimes, and even total breakdown of society after the Khmer Rouge’s takeover. Troubled by regional politics and memories of genocide, it was markedly different from the postcoloniality of Euro-America.

This plurality of the postcolonial formed yet another overarching theme of the symposium. Tzu Nyen Ho’s discussion of the high altitude and rugged terrains of Zomia and the patched archipelagos of the Sulu Sea pointed to an intricate link between geographies, state control, and militarism in postcolonial Southeast Asia. Nyen Ho’s study of the constructed unity of Southeast Asia dovetailed with Hiroki Yamamoto's project of writing a postcolonial art history for East Asia, a unique region with its own set of military political constellations. Hiroki Yamamoto’s presentation on the concept of ‘returnees' art’, borrowed from Park Yu-ha's notion of ‘returnees' literature’, is particularly insightful here.6 While ‘returnees' literature’ has the power to elucidate through literary means the lived reality of the Japanese who returned from occupied territories after the second World War, ‘returnees’ art’, as in the works of Kobe-born artist Tomiyama Taeko, expounds on the troubled representation of Japanese colonialism enabled by the artist’s movements between the mainland and the colonies. Yamamoto thus highlighted a new approach to writing East Asian art history, one which aims to ‘reconstruct a more cross-border, dynamic view of postcolonial East Asia’. The contentious nature of this postcoloniality became apparent through Jung-Yeon Ma’s contribution on the representation of Japanese-Korean history through contemporary art and Nodoka Odawara’s compelling discussion on the controversial lives of public monuments in Japan. For Odawara, statues embody in concrete forms the aspiration for cultural and societal endurance. Their removal or demolition as such signals a sign of shifting realities, where existing values meet public trials. This discussion on the legacy of Japanese militarism and sculptural arts thus helped historicise the ongoing global conversations on Black Lives Matters and the wave of statue removal that swept across the United States in its wake.

Nodoka Odawara giving her presentation ‘Why Sculptures Are Erased: “The Other Tokyo Tribunal”’ as part of ‘From Alexandria to Tokyo: Art, Colonialism and Entangled Histories’, 4 December 2020

Studying the multiplicity of the postcolonial entails a revision of many Asian countries’ complicated historical position as both coloniser and colonised. In this regard, Pamela Corey examined the many ways the current Vietnamese state has suppressed historiographically any narrative that might trouble its legitimacy and power. The cultivation of a nationalist discourse on territorial integrity and heroic resistance against foreign aggressors herein involves socially inculcated geographies of belonging, sustained through education, mass media, pomp, and rituals. What Corey called ‘the duality of Vietnam’s postcolonial self’ has parallels across Asia. Indeed, Ana Bilbao assessed the Singaporean experience as both a former colony and, after 1965, a colonising power. Singapore’s relentless extraction of Cambodian sand has constituted a process of neocolonial exploitation of land and labour that resulted in the devastation of Cambodian ecosystems and its rural livelihoods. In a world of endless commodities, one wonders if one can ever be excluded from the neo-colonial forces that stack up Singaporean high-rises on extracted Cambodian soils.

Clockwise from top left: Ming Tiampo, Fiona Amundsen, Wenny Teo and Ana Bilbao during the panel discussion ‘Against the Neo-colonial', part of ‘From Alexandria to Tokyo: Art, Colonialism and Entangled Histories’, 4 December 2020

To come back to Appiah’s point, there is hardly one postcolonial condition. Postcoloniality operates in hybrid manifestations across the world, troubled by localised hierarchies and lingering memories of conflicts, glossed over by finances and the alluring call of global capital. Given its online format, From Alexandria to Tokyo nevertheless succeeded in driving this point home. Its multifaceted panels, despite the limitation in time and interaction among the presenters, activated a global discussion in which a multiplicity of voices, opinions, and locales coexisted. What does multiplicity bring? The possibilities for decolonisation and reckoning with one’s colonial pasts. Wenny Teo’s penultimate presentation on the work of video artist Fang Di aptly commented on this note. Fang Di’s art lies at that precise confluence of uncomfortable hybridity and muddled authenticity that characterises the frontier of Chinese neocolonial ambitions. To operate from such a position means to think creatively about decolonisation. Meanwhile, following Māori filmmaker Barry Barclay, Fiona Amundsen made a case for the ‘listening camera’, a strategy of deep, visual listening to locate the past in the present, ‘where the legacies of this history live on in contemporary life and bodies, voices and places’. Listening closely to the images beyond one’s vision, one might even find the postcolonial at last – that specter of the colonial, stubbornly lingering on.