Fig.1

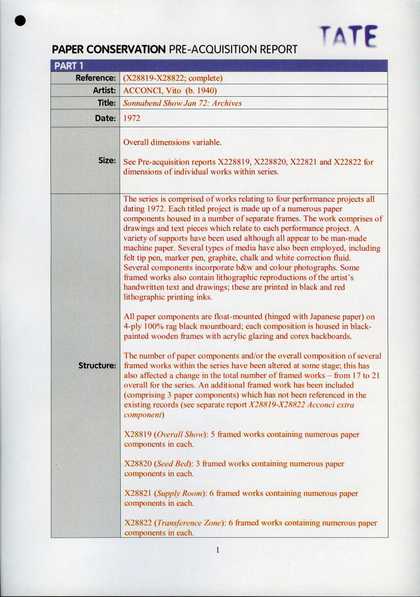

Pre-acquisition report for Vito Acconci’s Sonnabend Show Jan 72: Archives 1972

Tate Archive PC10.4

In 2009 Tate acquired a collection of items relating to three performances by the American artist Vito Acconci. With this single accession, the museum added to its collection Seedbed (Tate T13176), Transference Zone (Tate T13178) and Supply Room (Tate T13177), all from 1972. The documents relating to these three performances entered the collection at once because they are all constituent pieces of a larger conglomerate, which is itself billed as a work of art (as recorded in the museum’s pre-acquisition report, fig.1). This work, Sonnabend Show Jan 72: Archives 1972, is comprised of four discrete elements.1 The first three refer to the three performance works, taking the form of rectangular boards emblazoned with photographic documentation of the actions, as well as notes and plans – the conceptual framework for each piece – rendered in typescript and Acconci’s almost painterly scrawl. The fourth piece, Overall Show (Tate T13175), takes a bird’s eye view of the exhibition of these works at Sonnabend Gallery, New York: it shows hand-drawn maps of the show’s layout and more documentation of the displayed works. Thus Sonnabend Show Jan 72: Archives translates three performances into four graphic displays, then turns these four documentary compendia into one archive, finally presenting the archive as a work of art. This alchemy prompts a re-evaluation of the line separating archival holdings from artworks.

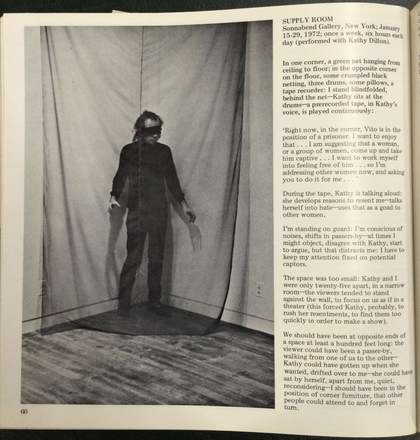

The three performance pieces included in the 1972 Sonnabend exhibition have earned places in performance history for the sheer aggression of the interpersonal relations established between performer and audience. In each one Acconci explored discomfiting experiences of control and subjection in the space of the gallery. For Supply Room Acconci stood blindfolded in the corner of a room while his then-partner and sometime collaborator Kathy Dillon sat in the opposite corner and banged a drum, speaking aloud ‘reasons to resent [Acconci] – talk[ed] herself into hate – us[ed] that as a goad to other women’, who, by means of a pre-recorded message issuing from a tape recorder, were invited to ‘come up and take [him] hostage’.2 This work was performed on Thursdays during the exhibition.3 For Transference Zone, performed on Tuesdays and Fridays, Acconci locked himself in a room surrounded by images and objects that reminded him of several people personally important to him. When audience members knocked on the door, they would be admitted one at a time. Once inside, Acconci treated them as though they actually were one of these people; he would transfer his feelings for that absent special someone onto the body of the gallery-goer.4 For Seedbed, which took place on Wednesdays and Saturdays, and became the most well-known of the three, the artist lay under a ramp built to be continuous with the gallery floor while he masturbated and intoned fantasies occasioned by the presence of the audience above. A microphone and speaker projected his voice through the room relayed: ‘My voice comes up from under the floor: “You’re pushing your cunt down on my mouth … You’re pressing your tits down on my cock … You’re ramming your cock down into my ass.”’5

The psycho-sexual drama performed in these works has meant that most scholarly attention has focused on the relationship between performer and audience. For most commentators, ‘intersubjectivity’, or how the artist and gallery-goers encounter and affect one another, has been the watchword. Acconci featured in Lea Vergine’s 1974 book Il Corpo come Linguaggio (The Body as Language) in which she argued that in body-based performance art the work of art consists in the creation and exploration of a relationship between artist and audience through their physical confrontation. This basic formulation has remained largely unchallenged. Twenty years after Vergine, the art historian Kate Linker averred that the erotics of mastery at work in Acconci’s performances are ‘radical’ insofar as they acknowledge the central role of the viewer in the production of an artwork.6 Also in 1994, Amelia Jones built on this theoretical position to argue that Acconci’s work could be read as a frontal assault on (masculinist) modernist myths of artistic self-sufficiency.7

While these analyses offer important insights into the structure and effect of Acconci’s work, they also root it in the intersubjective exchange between those physically present in the gallery.8 Sonnabend Show Jan 72: Archives complicates this reading, proposing that the process of ‘documentation’ be given more focus, especially because it serves as a comprehensive record of the exhibition’s experiments, attitudes and effects.

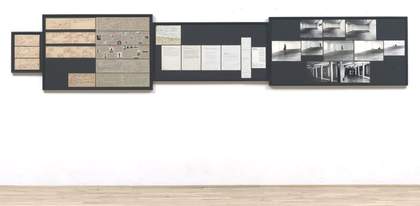

Fig.2

Vito Acconci

Sonnabend Show Jan 72: Archives. Overall Show 1972

Tate

© Vito Acconci

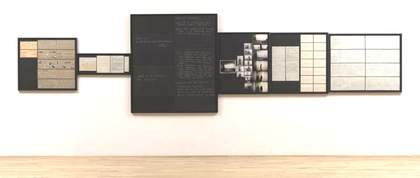

Fig.3

Vito Acconci

Sonnabend Show Jan 72: Archives. Seedbed 1972

Tate

© Vito Acconci

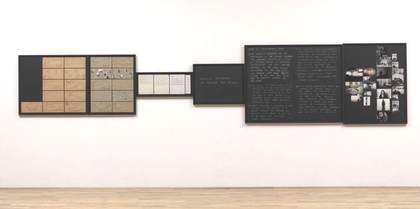

Fig.4

Vito Acconci

Sonnabend Show Jan 72: Archives. Supply Room 1972

Tate

© Vito Acconci

Fig.5

Vito Acconci

Sonnabend Show Jan 72: Archives. Transference Zone 1972

Tate

© Vito Acconci

The fact that Acconci created these graphic works and collected them into a unified piece suggests that he saw the show as one entity made up of many parts (figs.2–5). Moreover, the addition of the Overall Show implies that he saw that entity as something composed, like a choreographed procession. Indeed, when we look at the elements of Sonnabend Show Jan 72, it becomes clear that the composition is made not only of so-called documentary traces – photographs or subsequent written accounts of the work – but also of prospective plans in the form of notes and diagrams. Each of the performances is ‘recorded’ both before and after its execution.

This confusion of the temporalities of the work indicates that Sonnabend Show Jan 72: Archives does not attempt to capture the particularised, personal dimension or real-time experience of any of the performances. Rather it recapitulates its own set of programmes for structuring those interpersonal relations. This slight reorientation from personal experience to designed forms of interaction suggests that the performances were less dependent on the specifics of a given viewer’s contribution to the work and more focused on determining what that viewer’s experience might be from the outset. That is, while these performances needed viewers, those viewers had little or no agency in how the work would eventually materialise or transpire. So, if you came to the gallery on a Tuesday during Transference Zone, Acconci already knew he was going to pretend you were his father. But if it was Saturday he was already in the middle of mentally fondling you before you arrived and occupied the set of Seedbed.

Less interested in audience interaction as an aleatory procedure, the performances, as their attendant ‘archives’ attest, were chiefly focused on how transformations of space could produce specific psychological states of victimisation or empowerment. As Acconci put it in an interview in 2011, ‘instead of being a point in or on the space, I wanted to be part of the space.’9 This merging of the man with the gallery was perhaps most literally expressed in Seedbed and it is tempting to see in that gesture the germ of Acconci’s later self-reinvention in the 1980s as an architect. At any rate it demonstrates Acconci’s interest in manipulating the gallery’s physical rooms to shape predetermined encounters with his person, warts and all.

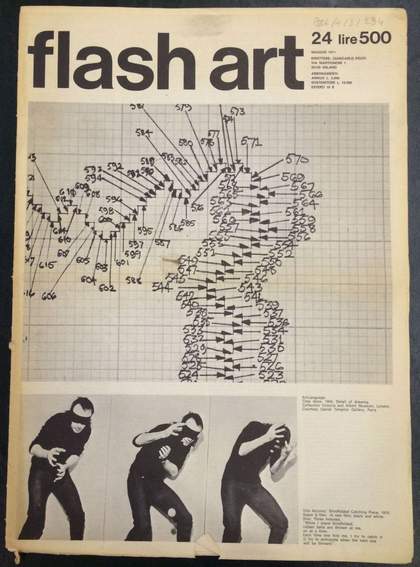

Fig.6

A still and excerpt from Vito Acconci’s Blindfolded Catching Piece 1970 on the cover of Flash Art, May 1971

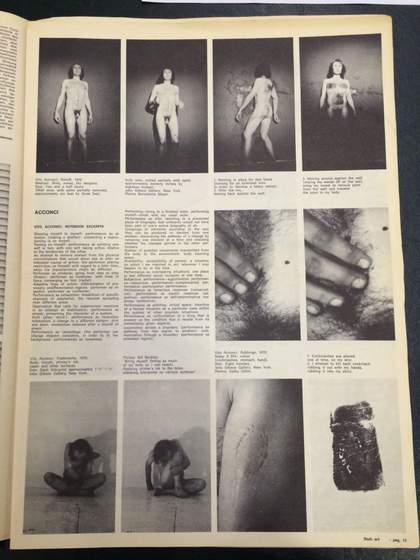

Fig.7

Vito Acconci, ‘Notebook Excerpts’, Flash Art, May 1971, p.11

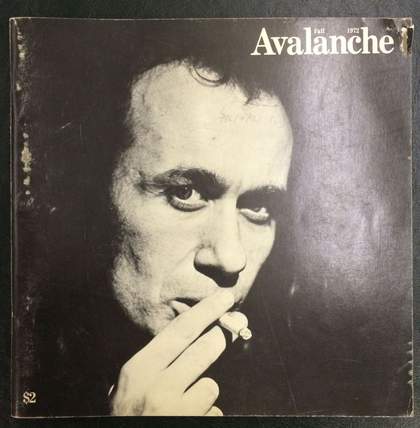

Fig.8

Photograph of Vito Acconci on the cover of Avalanche, Fall 1972

Fig.9

Vito Acconci, ‘Supply Room’, Avalanche, Fall 1972, p.60

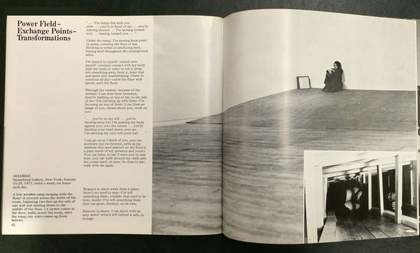

Fig.10

Vito Acconci, ‘Power Field – Exchange Points – Transformations’, Avalanche, Fall 1972, pp.62–3 (with details of Seedbed)

There is a close conceptual connection between Acconci’s experiments shaping architectural space, his authorship and his other modes of self-dissemination. It is unlikely that the performances were contingent on the live responses of the visitors – the idea functioned as the machine to make the works, even if they also comprised Acconci’s actions and his audience’s reactions. This explains to some extent why Acconci compiled his Sonnabend archive and imagined that it might convey the full import of the performances, bringing them to a final culmination, like laboratory reports on successful experiments. Such processes of cataloguing, or reporting from the field, were increasingly common ways for artists to distribute their works and encounter the works of others. Sonnabend Show Jan 72: Archives looks remarkably similar to contemporaneous layouts of Acconci’s works – including Supply Room and Seedbed – that appeared in Flash Art in 1971 and Avalanche in 1972 (figs.6–10). This is not to suggest that Acconci’s sense of form derived from these international magazines, but to serve as a reminder that Acconci was well practised when it came to crafting aesthetic experiences for audiences at a temporal and spatial remove as well as that communicating the essence of his art to a far-flung, albeit interconnected, audience was already on his mind. In both the magazine features and Sonnabend Show Jan 72: Archives the interaction between text and image shaped the viewer’s experience, regardless of their not having seen the performances.

Fig.11

Vito Acconci

Walking Performance / Letter to Barbara Reise 1969

Tate Archive TGA 786.5.2.1

There is another wrinkle to be added in this media ecology; it concerns the status of other archival elements. Acconci’s performances also travelled in correspondence to would-be collectors, critics and friends as typewritten documents. One document details a performance of 1969 for which Acconci walked toward a gallery opening from another part of town, telephoning the gallery with an update on his location every ten minutes (fig.11). Acconci sent this record to Barbara Reise, critic and editor of Studio International, as an example of recent work. Although this piece sits on the same ontological fault-line as Sonnabend Show Jan 72: Archives, it is held in the Tate Archive, not in the museum’s main collection. It would be easy to assert that it is not a work of art because it has not undergone the same compositional treatment as the records in Sonnabend Show Jan 72: Archives. However, the distinction seems to be more a result of space, or rather an effect of place. Acconci’s archive became an artwork because it was positioned as such, first by the artist and then later by Tate. The record in the Reise collection, though, ceased to be an artwork when she treated it as correspondence, placing it with other letters and proposals for artists’ projects. As such, it made its way into a physical archive, where it now remains.

Ultimately the difference between an archival record, a work of art and a magazine spread has to do with its relative position within systems of distribution. The shapes of these channels inform the treatment of the objects, ideas and even the people that flow through them. This is the lesson Acconci’s works communicate, whether experienced in the moment, in the flesh, or at a more distant remove.