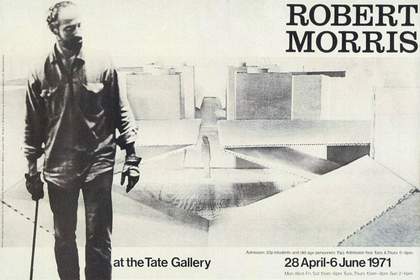

Fig.1

Exhibition poster for Robert Morris, Tate Gallery, 1971

Tate Archive TG 106.152

When Robert Morris’s 1971 exhibition at the Tate Gallery (fig.1) closed on 7 May, just four days into what was intended to be a five-week-long run, nobody could have guessed it would reopen thirty-eight years later. The 2009 exhibition, titled Bodyspacemotionthings, featured nearly all the same sculptural components – now conceived as a single work – and was staged in Tate Modern’s vast Turbine Hall. On this occasion, the show, which was scheduled to last only four days, remained open for three weeks. The temporal divide that separated the first truncated exhibition from its extended doppelganger affords an opportunity to compare the two versions of the artwork and to see just how much museums, audiences and ideas about art have changed in the intervening period in response to the provocations of performance.

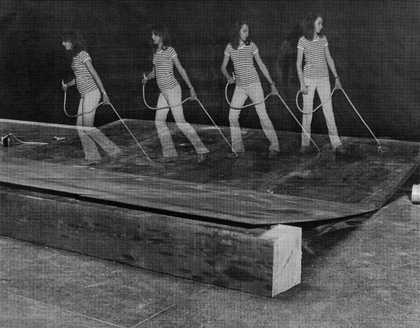

Fig.2

Photograph of visitor pulling a rope in Robert Morris, Tate Gallery, 1971

Tate Archive Photographic Collection

The 1971 show was first envisaged as a retrospective but Morris had other ideas. Rather than displaying previous works, the artist filled the length of the Tate Gallery’s (now Tate Britain’s) sculpture hall with a series of new ‘interactive’ sculptures that would experiment with conceptions about sculptural space and human physicality by having museum-goers put their own bodies to the test. The objects themselves were largely composed of rectilinear planes and blocks, triangles, spheres and cylinders, all made of industrial materials that, Morris insisted, could and should be reused when the exhibition was over and the objects dismantled. One piece consisted of a double ramp, made out of two steel plates forming a shallow ‘V’, propped under their outer edges on wooden beams (fig.2).

While the objects recalled Morris’s most iconic minimalist works, the exhibition’s emphasis on physical interaction made literal his ideas about the viewer’s involvement in the work of art. In 1966 Morris famously wrote of his approach to sculpture, ‘The object has not become less important. It has become less self-important.’1 The object was less self-important because it was now understood to unfold ‘in time’, subject to the perceiver’s experience of the context of reception – including space, light, and one’s own body – what Morris called ‘the entire situation’.2 The object, then, functioned as a locus of attention that heightened awareness of these other facets of aesthetic experience, a kind of phenomenological mirror in which one could see oneself seeing.

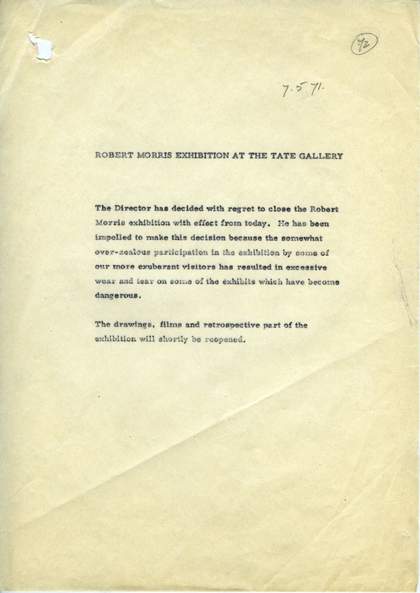

Fig.3

Draft press release concerning the closure of Robert Morris, dated 7 May 1971

Tate Archive TG 92.236.1

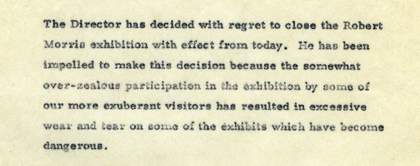

Fig.4

Draft press release concerning the closure of Robert Morris, dated 7 May 1971 (detail)

Tate Archive TG 92.236.1

The 1971 Tate exhibition magnified this reflective capability by turning the sculptural forms into objects of use. The double ramp (fig.2) was strewn with weights tethered to ropes, which one was invited to drag across the surface, experiencing both their heft and the slope of the terrain. A fibreglass sphere of roughly human-size diameter was positioned under a rope fixed to the ceiling so visitors could attempt to balance on top of it while rolling it with their feet through a circular course laid out in sandbags. There were also large wooden planks centrally placed atop horizontal cylinders that resembled standing see-saws and a wooden construction that looked like a series of chimneys that people were supposed to inch their way up, among many other challenges. Speaking to BBC presenter Melvyn Bragg, Morris asserted that the exhibition was ‘an opportunity for people to involve themselves with the work, to become aware of their own bodies, gravity, effort, fatigue, their bodies under different conditions’.3 The objects were catalysts to feel oneself feeling.

In the event, what the visitors felt did not always correspond with what was intended. The exhibition was popular, with over 2,500 visitors in those first four days. Audiences seemed to delight in testing themselves and the objects but they were also getting hurt navigating what one critic referred to as the ‘Action Sculpture’.4 One sprained finger, another torn leg muscle and fourteen reported cases of painful splinters, along with an incredulous and sometimes hostile reception in the press – one editorial suggested the exhibition was ‘no more than a child’s playground’ – brought the show instant infamy.5 Tate set up a casualty station and ordered 100 pairs of trainers to be kept on-hand for visitors’ use, but it soon became clear that what Keeper of Exhibitions Michael Compton called ‘over-zealous’ and ‘exuberant’ participation was causing the objects themselves to deteriorate and break apart, which increased their potential to cause harm as time went on (figs.3, 4).6

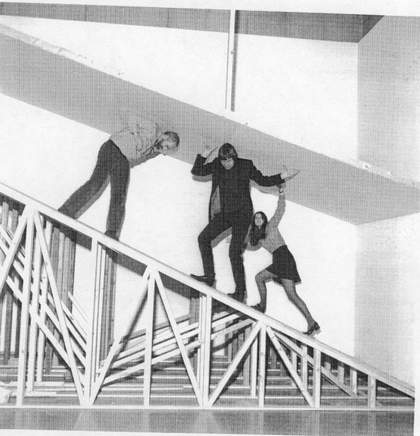

Fig.5

Robert Morris

Robert Morris 1971

Exhibited at the Tate Gallery, 28 April – 7 May 1971

Tate Archive Photographic Collection

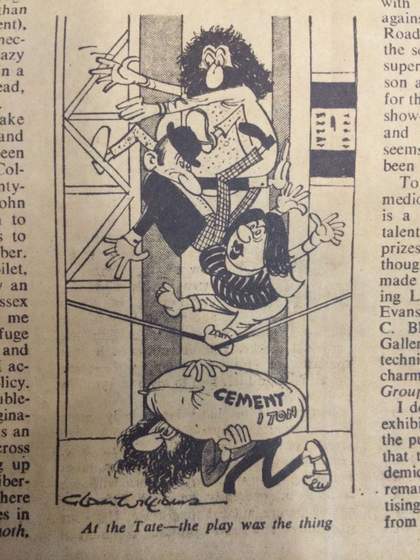

Fig.6

‘At the Tate – the play was the thing’ cartoon, Spectator, 8 May 1971

Tate Archive

It was more than a little disingenuous, however, to blame visitors for their own injuries. It was true that people largely ignored the instructional photographs that accompanied each object, using the works in any way they wanted. Before the show’s opening, Tate staff had posed for photographs depicting the intended method of meeting each challenge; these images were affixed to the appropriate pieces (fig.5). These black-and-white how-to pictures featuring slick young staff members contrast starkly with caricatures that circulated in the press (fig.6). Yet what the injuries, and the institutional reaction alike, demonstrated was just how unprecedented the show was.

The exhibition was the first of its kind in a major museum. Visitors might not have understood how each work was meant to deliver a specific mode of experience, but it is clear that they were ready to engage with art in this new way. Tate and Morris, on the other hand, were unprepared to deliver what they set out to create. The show was understaffed and the materials used in producing the objects – in keeping with Morris’s wishes – were rough and unfinished. This is not to say that ‘health and safety’ concerns should have dictated the shape or scope of the exhibition, but insufficient thought had been given to how the museum could support the functioning of the works, which is a principal role and duty of a gallery, no matter what is on display. Morris’s sculptural installation challenged people’s bodies, albeit in unexpected ways; moreover it worked in equally unpredictable fashion to describe its ‘entire situation’. It demonstrated its own radical newness in stretching conventions of museum display to their breaking point.

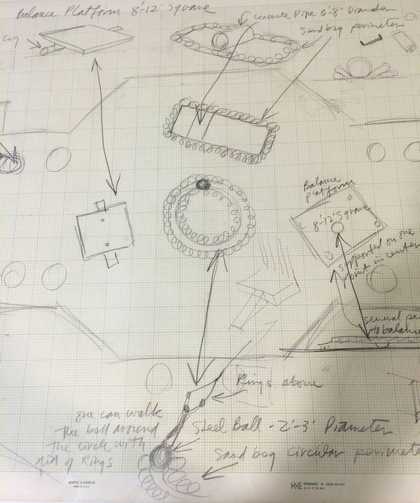

Fig.7

Robert Morris’s hand-drawn, aerial-view plan 1971

Tate Archive TGA7814

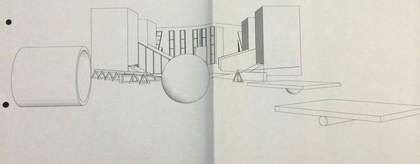

Fig.8

Detail of Robert Morris’s hand-drawn, aerial-view plan 1971

Tate Archive TGA7814

While the restaging of Robert Morris as Bodyspacemotionthings in 2009 was a comparative success – it ran for three weeks rather than its planned four days – it too highlighted the physical and institutional environment in which the exhibition took place. Curators worked with Morris to re-imagine the show for the Turbine Hall in Tate Modern. Some elements had to be left out because the Turbine Hall is not as long as the Duveen Galleries in what was the Tate Gallery and is now Tate Britain. The restaging also required collaboration with industrial fabricators to ensure the objects were constructed to be faithful to their forebears but also more user-friendly. There were more staff on-hand to guide and help visitors. The physical challenges posed were identical, but the pieces were now made with the idea of heavy use in mind: they were reinforced and the materials themselves were of higher quality. There was no more unfinished plywood, no more splinters. The difference between the ad hoc estimates of Morris’s hand-drawn aerial view from 1971 and the 3-D digital rendering made by the constructors employed in 2009, conveys a sea change in the institution’s approach to such participatory projects (figs.7, 8, 9).

Fig.9

Digitally rendered plan for Robert Morris, Bodyspacemotionthings 2009

Tate Archive EXM 5.7 62b/05/5A A34397

The effect of these material fixes is not to be underestimated, but a curator’s note from the planning stages of Bodyspacemotionthings gets to the core of the matter: ‘Audience [sic] have greater experience of participatory work and Tate is now much more experienced in staging this type of project’.7 In the interval between the two exhibitions, the museum and art audiences had become accustomed to the notion that an artwork would make immediate demands on a viewer’s body and that it would require action as prerequisite to reception – or, quite simply, that these are not antithetical operations.

It is impossible to make proclamations as to whether visitors to Bodyspacemotionthings were moved to appreciate anything new about themselves, or just had a good time, although the two are not mutually exclusive. What we can learn from this brief exploration, however, is that audiences now expect to be involved in the work they encounter, to be offered an experience to negotiate. This expectation has developed, to no small degree, in response to the incursions different forms of performance have made into the space of art, slowly expanding it and reconfiguring its borders. It has become the responsibility of artists and institutions to shape this involvement and to make it visible, not for its own sake, but because it is necessary if we are to reflect on the changing nature of our ‘entire situation’.