Fig.1

Installation view of work from Rebecca Horn’s body-sculptures series, including Moveable Shoulder Extensions 1971, Tate Modern 2016

Tate

© Rebecca Horn / DACS, 2016

German artist Rebecca Horn’s body-sculptures are a series of wearable sculptures, fashioned from fabric, wood and metal, and designed to extend and enhance the movements of the human body. Moveable Shoulder Extensions 1971 (Tate T07860) is one example. Intended to be used for a single performance, where body and sculpture interact to explore movements and spaces, the body-sculptures are now exhibited as static pieces, or as one critic has described, ‘like tack hung on a stable wall’.1 Documentation of the performances, as well as texts and drawings hang alongside the objects. This form of display has the effect of blurring the line between one work and another, encompassing imagination, creation, documentation and exhibition. Rather than a singular artistic work, the viewer faces a network of interconnected objects all supporting one another in their individual acts of performance.

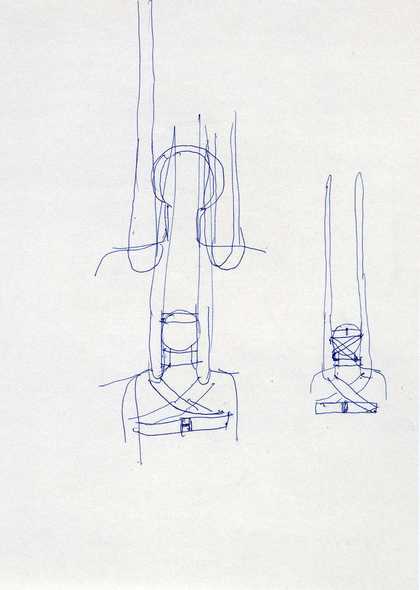

Fig.2

Rebecca Horn

Untitled 1968–9

Tate

© Rebecca Horn / DACS, 2016

Moveable Shoulder Extensions offers a good case study of the life cycle staged in Horn’s body-sculptures series; the representation of the work across different media gestures to processes before, after and during the performance. The first iteration of the piece can be seen in a page of preparatory sketches (fig.2) that Horn produced three years before the construction of the sculpture. They show Horn’s designs for the work, including details of the straps necessary to secure the piece to the wearer’s body, as well as the overall visual image she hoped to create with the sculpture. While these sketches are indicative of the development of the work, the page is also part of Tate’s collection and is displayed as an independent artwork. The drawings illustrate Horn’s imagined performance, allowing contemporary viewers to engage with the artist’s process and to picture a performance which was, at that point in the work’s life cycle, still to come. Although these drawings could be approached as pre-documentation, they can also be viewed as the first life of the work: the imagined performance.

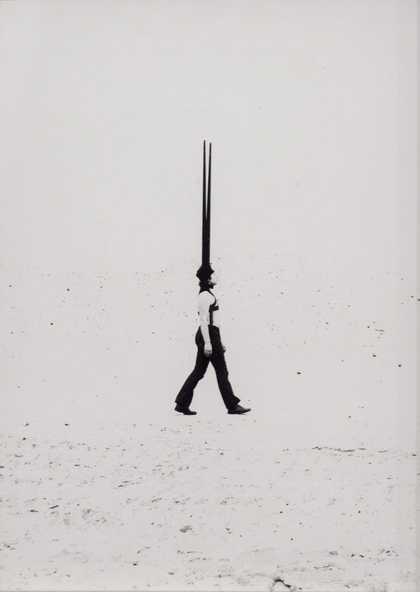

The second iteration of Moveable Shoulder Extensions took form in the film series Performances I 1972 (fig.3) and in a still image from the same year (fig.4), in which the performer is captured wearing the sculpture. The film sequence was enacted only once, in a remote setting without spectators, meaning that the film became the primary means of accessing the work and was the only record of the performance. The simple movements of the man as he strides across the desert background are meticulously investigated by the camera, which shoots from multiple angles, as if recreating the viewpoints found in the sketches. This allows for a fuller understanding of the relationship between sculpture and body. Like the sketches, the film also occupies a position in the Tate collection, defined as both an artwork and a document. We are kept at a distance from the time and space of the action, but the film and the photograph allow us access to the work both as documentation of what happened and as a stage in the larger conceptual life of the work. While the film and the photograph are documents of the work, by consciously making them the only way in which the spectator can experience the sculpture being ‘performed’, Horn also makes engaging with them a part of the performance act itself.

Fig.3

Rebecca Horn

Performances I 1972 (film still)

Tate

© Rebecca Horn / DACS, 2016

Fig.4

Rebecca Horn

Performance still with Moveable Shoulder Extensions 1972

Tate

© Rebecca Horn / DACS, 2016

The third iteration of Moveable Shoulder Extensions is the static, material sculpture (fig.5). Although the object was designed for the one-off performance, Horn also imagined that it would have an afterlife as an artwork in a collection. As such, the artist made specific decisions about how the works would be collected and displayed, insisting on making these conditions part of the artwork.2 One material outcome of this was the creation of specific boxes and cases for exhibitions, which have been described by some critics as being ‘like glorified prop boxes’ or even as ‘coffin-like’.3 While this suggests that the work is deadened through re-display, Horn actively embraces the changing nature of the work. In an interview, the artist reflected on the fact that the sculptures were used only once for performance, suggesting that this was because ‘the tension built up to a point and the performance, with its unique energy, just could not be repeated’.4 Her awareness of the changing energy of the artwork corresponds to the changing way the work is experienced. As it is no longer activated through performance, Horn treats the objects as sculpture. She discusses its preservation with conservators, designing exhibition materials for it and issuing specific instructions for its display. As a result the object sits somewhere between sculpture and performance prop, not only referring to the performance which has come before but also firmly performing its own identity as sculptural artwork.

Fig.5

Installation view showing Moveable Shoulder Extensions 1971 alongside the performance still (fig.4), Tate Modern 2016

Tate

© Rebecca Horn / DACS, 2016

Horn’s careful consideration of the post-performance existence of Moveable Shoulder Extensions takes on its final iteration in its display as a collective exhibition. The way in which the sculpture itself is displayed – mounted on brackets according to the height of the original performer – gestures to the performance it was created for as well as initiating a new bodily relation with the viewer. This experience is heightened in this display by the other elements, which show the work being performed. When seen together, the objects create a fuller experience of the performance: the performance-centric nature of the work is evident, as is its evolution from the imagined performance in the sketches, to the embodied and mediated performance in the video and the remembered performance in the exhibition of the sculpture and ephemera. One writer said of Horn’s pieces that, after their use in performance, ‘they have turned from props to protagonists, their independent reality becomes clear’.5 This ‘independent reality’ might be a performance that takes place only in the viewer’s imagination, prompted by the mediation of the assembled documentation or, perhaps, a remembered performance that gets as close as possible to that singular moment of performance, which would otherwise be lost to the spectator today.