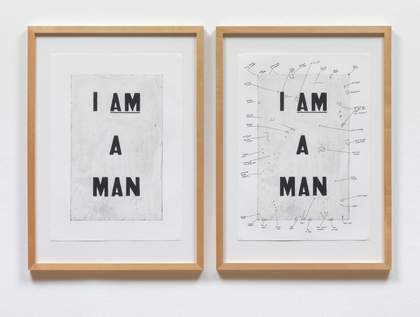

Fig.1

Glenn Ligon

Condition Report 2000

Tate

Condition Report 2000 (Tate L02822) by the American artist Glenn Ligon comprises two framed images, identical except that one is marked by annotations. Despite its apparently unassuming aspect it offers a profound meditation on the nature of speech, identity and history, and more particularly on the relationship between repetition and difference, as well as inherent meaning and the power of context (fig.1). The diptych reproduces one of Ligon’s earliest text-based paintings, Untitled (I Am a Man) 1988, which in turn borrowed its featured phrase, ‘I AM A MAN’, from one of the most famous episodes of the American civil rights movement of the 1960s. Condition Report follows on from, and traces, this chain of production across time and space, asking how the same utterance transforms when spoken in different ways, by different people. Condition Report draws viewers into a network of references that link together discourses of power and inequality, with the exploration of creativity and selfhood. What becomes clear as one makes one’s way through this web is the extent to which each of us inherits a set of potential roles and capacities based on one’s position within a network of power relations. As Ligon put it, ‘On some level one is always playing oneself’.1 Condition Report offers an opportunity to confront the mechanisms of history that have delimited the ways in which one can play oneself, as well as to ask what it might mean to question those boundaries.

The text prominently displayed on both panels of the diptych, ‘I AM A MAN’, derives from the placards carried by protesters during the 1968 Memphis Sanitation Workers Strike. On 12 February of that year, over 1,000 African-American men went on strike to achieve better pay, safer working conditions and the right to union representation. Up to that point the workers had received a minimum wage of $1.60 per hour for up to forty hours per week, though the completion of sanitation rounds pushed the time worked closer to sixty hours.2 These wages were so low that forty percent of the workforce qualified for welfare benefits.3 The equipment they were given to do their jobs was outmoded and unsafe: only two weeks before the strike two workers had been crushed when the bin of their truck malfunctioned. Furthermore, workers could be sent home, by their white supervisors, without pay and for any apparent infraction. Only a few days after the truck tragedy, supervisors sent sewer and drainage workers home during a rainstorm, while they stayed on the job (with nothing to do) collecting their day’s wages.4 This last insult salted fresh wounds and the men voted to strike.

The sanitation workers’ battle for more just working conditions became emblematic of the larger struggle roiling the United States. It occasioned boycotts, sit-ins and marches across the city, and attracted national attention with the help of several visits from Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. It was in Memphis that King delivered his famous ‘Mountaintop’ speech before being gunned down on his balcony at the Lorraine Motel on 4 April 1968. It was clear to people in Memphis and beyond that the mistreatment of the sanitation workforce and especially the mayor’s intransigence – Mayor Henry Loeb refused to bargain and threatened to fire and replace all the striking workers – was racially motivated and rooted in a ‘plantation mentality’.5 The proclamation emblazoned on the protesters’ signs, ‘I AM A MAN’ signalled this connection between the specific labour dispute and its wider import: the epochal and urgent struggle against systematic, discriminatory exploitation and dehumanisation. The placards voiced affirmative contradiction to the assertion that echoed through every facet of daily life structured by nearly eight decades of Jim Crow racial segregation laws and centuries-old foundations in the American history of slavery. These men demanded their humanity be recognised.

Ligon first borrowed this weighty phrase to produce one of his earliest text-based paintings, Untitled (I Am a Man) 1988. That work is almost a replica of the placards used in 1968. The artist imported the font and their placement against a white ground. Ligon also intervened in the form of the original, translating it into another register. Art historian and curator Scott Rothkopf has noted that Ligon altered the spacing.6 Whereas the placards read ‘I AM | A MAN’ (text on two lines), Untitled says, ‘I AM | A | MAN’ (text on three lines). The difference is subtle, but this variation perhaps suggests another kind of distance – namely the temporal expanse of the twenty years between the placard and the painting.

Fig.2

Memphis Sanitation Workers’ Strike display

National Civil Rights Museum, Memphis, Tennessee

http://civilrightsmuseum.org/project/i-am-a-man/

While Ligon’s painted lettering is black, the original text on the placards was red (fig.2).7 If this detail usually goes unremarked in relation to this work, it is because the popular familiarity with Ligon’s source material is predicated on black-and-white photographs of the sanitation workers’ protests taken by Ernest C. Withers (visible in the background of fig.2 above). Indeed Ligon has said that the idea of using the slogan came to him on seeing one of these photographs in the office of US congressman Charles Rangel while working as an intern at the Studio Museum in Harlem.8 Whether Ligon knew the image he saw converted red writing to black or not, the fact that he represented its reproduced and widely circulated appearance – rather than its ‘original’ form – further highlights that he approached the statement at a historical remove. Untitled (I Am a Man) begs the question: can this painting replicate the same utterance, or does its meaning somehow change as it moves across time and space?

To grapple with this question and take stock of the civil rights slogan’s reiteration, commentators have had to account for both how cultural politics had shifted in the intervening span of time and how racialised vision had persisted. Anchoring this endeavour in the play between the repeated text and the painting’s literal ground of gestural white brushstrokes, art historian Darby English has argued that Untitled (I Am a Man) was ‘the first work in which Ligon’s desire to fuse ostensibly irreconcilable representational modes – the formalist painting, the political statement and the private question – resulted in something fraught but whole’.9 Before making text-based paintings Ligon had painted abstract expressionist-style canvases, but by superimposing ‘I AM A MAN’ on top of such brushwork, Ligon alluded to the way his own work was never received as that of an ‘artist’ but always as that of a ‘black artist’. Art historian Huey Copeland has written that even in ‘the salad days of identarian critique’ that were the late 1980s and early 1990s, ‘mainstream criticism … trivialized the work of black artists even as it was brought forward to capitalize on the reigning taste for alterity’.10 Ligon’s own identity, or others’ perception of it, would pop out in relief from the surface of his works, making it subject to different criteria of evaluation than the work of other (read: white) artists whose identities could remain submerged, seemingly beside the point – like a supposedly neutral background.

By taking up the words of the Memphis workers, Ligon was not demanding his humanity be recognised, in order that his work be considered in terms of artistry rather than blackness, so much as staging the fact that the demand still had traction in a very different context. That is, he not only acknowledged how the discourse of racial identity affected the reception of his art but also used his work as a platform to showcase the limits that history placed on his role as an author. As Ligon put it, art ‘has been a treacherous site for black Americans because [it] has been so tied with the project of proving our humanity through the act of writing’.11 Ligon’s appraisal not only drives home the poignancy of the 1968 strikers’ need to proclaim their manhood with a slogan, but also links that event and his reiteration of it with the nineteenth-century tradition of the slave narrative. For former slaves, ‘demonstrating proficiency in language arts became a form of resistance’, wrote scholar Kimberly Rae Connor, ‘a literal and literary way to articulate the humanity of black Americans’.12 It is the apparent persistence of the need for such resistance on which Ligon’s work shines a bright light. As Copeland put it, ‘Ligon’s work enacts a kind of repetition familiar to students of African American culture, so that history, text, and performance become circulating quantities always subject to reiteration and renewal’.13 So even as Ligon gives voice to his own authorship, he also demonstrates the extent to which that authorship is spoken for him, through him, issuing from elsewhere.

Ultimately even the ‘I’ in ‘I AM A MAN’ comes under pressure. Is it Ligon who speaks? This last question animates Condition Report. Made twelve years after Untitled (I Am a Man), this work adds another link to the chain of iterations. This time, however, Ligon distanced himself from the act of enunciation by turning his painting into a reproducible print and collaborating with conservator Michael Duffy. It is Duffy’s annotations that we see on the diptych’s right side. He has marked cracks and smudges, the wear and tear of the painting’s travels. The two images side by side produce a kind of visual dissonance. On the left the familiar vision of Untitled (I Am a Man) bodies forth, while on the right the words are surrounded by hand-drawn lines, circles and notes. These marks flatten the image of the painting, turning the image of the entire text/ground relation into the background that supports Duffy’s additions.

It is tempting to suggest that the effect of the juxtaposition amounts to a kind of ‘before and after’ parable, an assertion that the critique mounted by Ligon’s original has been subsumed into the background – that is into the cultural context that informs how we think about race and subjectivity in the twenty-first century. That it has become a historical artefact, without bearing on the later moment. However, the diptych’s redoubled insistence on the surface qualities of Ligon’s painting more likely signals the opposite: because even the most minute deviations from ‘purity’ on the white ground itself stick out, reveal themselves as matter in the wrong place. The supposedly neutral background has not disappeared, but become more intolerant of difference.

This is not to suggest that this conservational exercise was invested with particular sociological implications by either Ligon or Duffy. Indeed, the enunciating ‘I’ has receded, as reproducibility has replaced manipulated citation (as the mode of production) and the smudge has supplanted the slogan (as the conspicuous figure). Rather, the point is to see how powerful are the categories that inform our apprehension. As a conservator, Duffy naturally focused on identifying threats to the canvas’s integrity – such was his role; he could only police the background’s border. As a work, Condition Report both concretises and expands the argument made by Untitled. Each of us inherits a part to play based on our position in a historical chain. To say that daily life is performance is to acknowledge how history has shaped the contours of how we understand and are understood, which makes it all the more vital to interrogate what we conceive as given.