Liu Ding is a Chinese artist and curator, born in the Changzhou Jiangsu province and now living and working in Beijing. Ding was invited to create Almost Avantgarde for the BMW Tate Live: Performance Room, which was streamed live from Tate Modern on 13 June 2013. The web broadcast was an exclusive one-time event and watched in real time by an online audience. After the performance finished, there was a live question and answer session between Ding, his artistic collaborator and translator Carol Yinghua Lu, and curator Catherine Wood using questions posed by viewers via social media channels such as Facebook, Twitter and Google+. Ding transformed the Performance Room into a typical party scene – complete with mingling guests, a DJ and drinks. A number of artworks from Tate’s collection were displayed throughout the space, such as Gilbert & George’s portraits and Carl Andre’s Steel Zinc Plain 1969 floor piece. The live feed switched back and forth from the party scene, where only the DJ’s music could be heard by the audience, to text slides which Ding had prepared, which were English translations of the Chinese voices heard narrating anecdotes from their experiences within the art world.

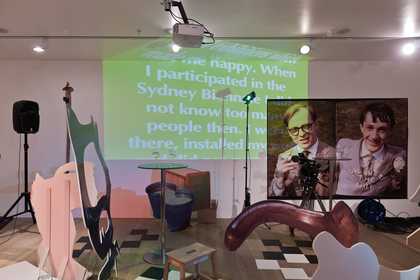

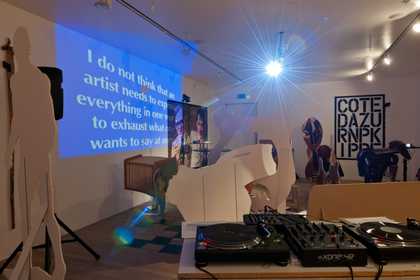

Ding invited art professionals and members of staff from the Tate to have a small party in the performance space. The scene appeared akin to an art salon, or private view at a gallery. A selection of modern artworks from the Tate collection, all from the Western canon, were reproduced as facsimiles and exhibited in the space. These flimsy prop versions were made out of paper and cardboard. Two turntables were set up so that a DJ could intermittently mix a soundtrack of Baroque chamber music with records of different audio testimonies spoken in Chinese. Ding was ‘attracted to the repetition [in baroque music] … the same passage, the same rhythm appears again and again.’ In an attempt to highlight this feature, he had repetitive key moments multiplied numerous times within one track, so it appeared ‘even more repetitive, even more concise’.1 The music was the only audio track streamed to the live audience. Projected on the wall of the Performance Room, in white rolling text on various brightly coloured backgrounds, were English translations of the Chinese narratives. During these moments, the music and live stream of the party would cut out and the online audience would only see the projected screen in order to read the translation. The discussions had by the party guests were never audible. The audience saw the people speaking and gesticulating to one another on mute. This loss of sound made the spectator aware of the ‘invisible and visible performances and actions that are around us’ in the everyday.2 Similarly, the participants inside felt forced to create a performance of their own. Ding wanted them to stay conscious and alert, so it was a ‘dry’ party with no alcohol, in order for everyone consider their shared experience in a rational manner.

The audio narrations and quotes on the coloured slides arose from a year of research that Ding, Yinghua Lu, and others had undertaken about Chinese art and artists in the 1990s. In this process Ding interviewed and had conversations with artists, critics and curators active during that period. They discussed their working process, past experiences, and the expectations surrounding contemporary Chinese art practice. One particular conversation that Ding had with a Chinese conceptual artist who had been active in the 1990s inspired the concept for Almost Avantgarde. During the 1990s, driven by an aspiration for change and novelty, many Chinese artists began to experiment with different artistic forms, movements and threads of thought originating from the West. Ding believed that these artists ‘felt like they were quite avant-garde by being engaged in such experiments and thinking processes’, but it also meant that there was a pressure within the artistic community to create distinctly Western-looking work.3 The idea that to be ‘modern’ meant you had to be ‘Western’ was rife. There was a focus on anxieties about the external artistic inferences from the West, how they were positioned against each other and yet still simultaneously experienced. The design of the broadcast echoed this multiplicity of the communal experience. The audio and the text, the contrast of Chinese and English, allowed for a bilingual presence. The bilingualism disrupted a sense of consistency, symbolic of the ruptures in Chinese art history due to the complex relationship between East and West. The false sense of intimacy created for the online audience echoed the narrations, which explored a sense of belonging to and of alienation from Western art practice.

Ding is known for his multi-faceted artistic practice, which often involves curating, publishing and lecturing. Working within the context of the Chinese art industry, he has initiated projects that investigate how the logic of art systems, such as the market, bear a relationship to art history and methods of creative practice. This particular interest in art’s value system was key to the Performance Room project; ‘[in the 1990s] Chinese artists welcomed and embraced “new” and Western art forms and philosophical thoughts, they quickly entered themselves into a globalised context and actively participated in such productions’.4 Almost Avantgarde explored ambiguous and populist attitudes towards modern art, and the drive to create contemporary art. Ding’s use of well-known artworks was a device to create ‘a symbolic garden’ which could in turn operate as a reference to a shared experience of art.5 The crude, albeit almost humorous, artificiality of the artworks allowed Ding to create an explicitly manufactured space, perhaps suggesting how the drive to create artwork which would be popular in the West was particularly shallow and unstable.

The juxtaposition of absence and presence, which is at the core of the Performance Room project, operated on multiple levels in Almost Avantgarde. Ding explained, ‘certain things can be shared through live broadcast and certain things cannot’.6

The democratic nature of the Performance Room online space, which exists outside geography, meant that people from both West and East could be united as one audience through watching Liu Ding’s piece. Everyone could be present at the party to some degree.

Philomena Epps

July 2016