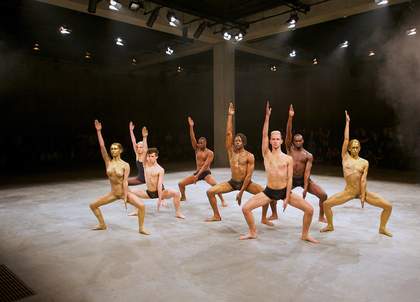

Amidst a Sea of Flailing High Heels and Cooking Utensils was a forty-minute performance choreographed by the artist Eddie Peake and performed by eight dancers. It took place on 21 July 2012 as part of the series The Tanks: Art in Action and was created specifically for that space. The work juxtaposed the fleshy spectacle of nude and semi-nude human bodies – which pulsated, writhed and danced to live music – with the stark, grey, industrial backdrop of the space’s cavernous, concrete interior. Drawing on poses from Italian Renaissance art, as well as contemporary popular and urban dance, Peake explored, exploited and exposed the human form.

The choreography investigated changing idealisations of the body through time, through postures lifted directly from well-known art historical and pop cultural sources. These ranged from the heroic stances characteristic of classicism, to the sexualised dance moves of contemporary music videos. In this way the performance became a moving montage of images, appropriated from different moments, places and contexts. Throughout the performance, statuesque poses – held in unison by the dancers in elegantly spaced formations – led into, and jarred with, raunchy, gyrating outbreaks of movement, creating what critic Skye Sherwin called ‘a heady fusion of timeless beauty and erotic charge’.1 Talking about the work, Peake said that in putting such an intense focus on the performer’s physicality, and jutting between moments of ethereal sensuality and raw sexuality, he hoped to evoke ‘a kind of bodily or guttural impact’ in the viewer.2

The performers were either dressed in underwear or nude and gilded in gold body paint, with each one muscular or toned. While some of the actions required the dancers hold still in contrapposto poses, others required fast aggressive moves, or slow and sensual dancing. Often the bodies were staged as desirable, although the choreography also saw them enact violence. At one moment, for instance, a gang of lithe bodies clambered onto a pile, struggled, thrusted – resembling a scene of rape – and then fell apart, like human rubble in the barren underground space.

Trapping the audience, in a sense, through their desire to look at other bodies, the work flitted in and out of such scenes; seducing viewers one moment before propelling them into more uncomfortable circumstances, thus making them aware of their own physical presence in the room and of the intimate relation of looking. As Peake has said, ‘Looking at a covetously desirable, sexual body inevitably has to become part of the subject matter. You’re as vulnerable as the performer if not more so.’3

Claire Gormley

October 2015