On 21 January 2014 Cally Spooner’s And You Were Wonderful, On Stage was performed in Tate Britain’s rotunda in front of a live audience. The first BMW Tate Live performance of 2014, the work was the first iteration of a two-part commission undertaken by Spooner for Tate that year (the second was a reworking of the same piece for a live web broadcast on 27 February 2014 as part of Tate’s ongoing Performance Room series).

The performance of And You Were Wonderful, On Stage at Tate Britain featured a twenty-six-strong, all-female chorus, which sang a series of prologues and overtures acapella, while performing simple choreography. Like much of Spooner’s work the scripted content of And You Were Wonderful, On Stage was derived from a variety of written and aural sources. The chorus sang harmonies following a call-and-response structure, which allowed the cultures of pop, politics and commerce to weave together. Comprising five acts, the performance recounted a series of separate events that took place in 2013: the singer Justin Bieber and his manager Scooter Braun’s hollow excuse for the star’s tardiness at an O2 Arena concert in London; the cyclist Lance Armstrong’s staged apology on the Oprah television show; the pop star Beyoncé’s lip syncing the American national anthem at the 2013 presidential inauguration; the U-turn by the British government minister Michael Gove on educational policy; and the revelation that Barack Obama’s script-writer Jon Favreau was leaving the White House to write movies in Hollywood, not only suggesting that the President might be rendered voiceless but also caricaturing similarities between political rhetoric and cinematic confection. Each event was the focus of a media spectacle in which public speech was exposed as choreographed. Having drawn her content from already highly ambiguous speech situations in which authenticity had become a style, Spooner’s chorus line further abstracted the language of these scenes by stressing, lingering upon and repeating moments in which verbal glitches, ticks and slips belied the appearance of spontaneity. The performance also drew on the explicitly polished, high-octane style of the Broadway musical genre, further accentuating the contrived nature of the language.

In addition to musing on the loss of live, unscripted or unmediated speech in contemporary life, And You Were Wonderful, On Stage disrupted the function of the chorus in performance. By relocating the chorus from the margin of the musical to centre stage, mixing the style of a Broadway musical with the classical conventions of the Greek chorus – where a homogenous, non-individualised group of performers collectively communicate dramatic action – Spooner disregarded plot and instead focused on what she identified as the very ‘mechanisms of language’ itself.1 Rather than illuminating the performance’s content, as the Greek chorus traditionally would, Spooner’s chorus divulged only disjointed snippets of stories, their speech patterns and the repetition of sounds dominating the meaning of the words themselves.

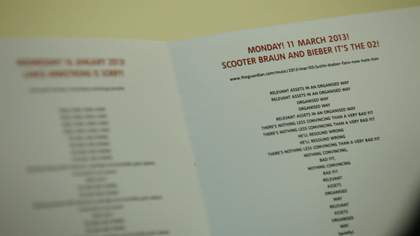

With the aid of a printed programme – which included headlines culled from newspapers, subheadings directing the audience to the internet resources used by Spooner to construct her script, and the lyrics for each act – viewers were guided through the progressively scattered and anxious musical renderings of these tragi-comic scenarios. The performance song lyrics were disrupted throughout by the technical jargon of corporate and PR language; the chorus singers’ increasingly robotic refrains rendered language less a form of expression than a process of standardisation, mechanisation and disguise. The algorithmic incantations of the chorus line finally petered out in an incoherent tangle of techno-babble, the speech sounding, as Alice Butler has suggested, as if it were ‘processed through a machine, its cogs destroying the syntax’.2

Not only could the performers in And You Were Wonderful, On Stage be read as machines – shrouded in minimalist grey and pastel printed outfits and delivering their lines with neither emotion nor recognition – but also the performance itself was conceived by Spooner as a kind of machine. It filtered, recoded and immersed its content in the digital each time it was enacted. For example, following the performance at Tate Britain, the internet-streamed event for Tate’s Performance Room interwove live action with pre-recorded footage, further exploring the relationship between computational information, communication, performance and reality through a process that resembled both collage and algorithm. Explicitly positioning itself between the realm of the art museum and the apparently culturally indiscriminate arena of cyberspace, this second iteration of And You Were Wonderful, On Stage exposed both venues as spaces in which voices, messages, images and subjects are carefully curated for our consumption.

And You Were Wonderful, On Stage is an evolving production that changes performers, script and choreography each time it is shown in a new location. This event at Tate Britain was the fourth adaptation of the work. The musical was composed by Peter Joslyn and devised with Rhiannon Drake, Helen Hart, Jenny Minton, Piya Malik, Rebecca Thorn and Chloé Turpin, with choreography by Adam Weinert and costumes by Malene List Thomsen.

Clare Gormley

April 2016