Bruce McLean’s performance Good Manners and Physical Violence took place in the South Duveen Galleries at Tate Britain (known at the time as the Tate Gallery) from 2 to 8 September 1985. The performance coincided with a show of McLean’s paintings, on view from 3 July to 8 September. McLean collaborated with Angus McCubbine and David Ward for the performance. Once a day at midday, and for around an hour, the men performed a set of exaggeratedly polite gestures, such as greetings or other commonplace social interactions, which slowly developed into more complicated and passive-aggressive physical manoeuvres. McLean also used props and actions to further address how certain types of body language can easily slip from polite mannerisms into crude aggression.

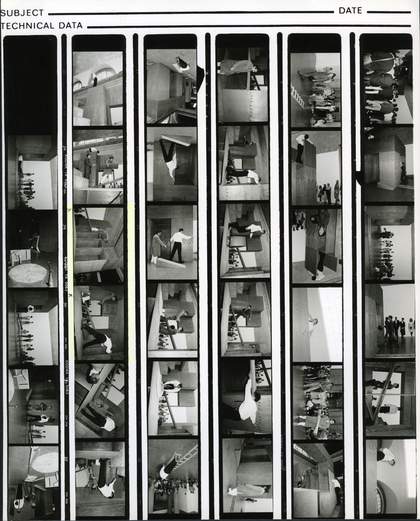

The performance took place within ‘the blue box’, a roughly painted structure that had been built and erected by McLean in the Duveen Galleries. It was constructed from 2.4 x 1.2 m wooden panels. The box – large at around 4 m x 7 m x 4 m – provided a manufactured, although still roughshod setting in which the action took place. Significantly it had also been designed with blind corners, passageways, steps and a seesaw. There were domestic objects including ladders and tables inside the box, which the performers could use. McLean, for instance, carried large rolls of linoleum around with him. These props symbolised the home but also provided a stage for the exaggerated labour of the performer’s actions.

In and around the blue box, McLean, McCubbine and Ward burlesqued good manners as meaningless gestures. Art historian Mel Gooding’s comments on the performance, collated with McLean’s notes, describe this descent: ‘excessive politesse (‘a slight one? at the neck, a considerable bend at the hip’), dim and uncomprehending conformity (‘I looked right, I looked left; I took one step forward, I took two steps back’) and a grimly robust physicality (‘Hello! What do you think you’re looking at’).’1 The actions and speech of the performers parodied behaviour associated with British nationality, which according to Gooding resulted in a ‘comic ballet of neurotically repeated moves and encounters’ that quickly gave way to offensive outbursts.2 As the performers worked to ‘out-do each other’ or ‘catch each other out’, good manners descended into violence.3

The performance props played a central role in illustrating the thin line between good manners and physical violence. McLean wore large red boxing gloves for much of the performance, making it impossible for him to carry out supposedly polite actions, such as shaking hands. Some of the other props have appeared in McLean’s paintings of the period: objects like chairs, ladders or rolls of linoleum in primary colours. McLean’s 1985 painting White and Blue Man, Grey Man, Red Lino is a good example of this. The duplicitous symbolism of the objects related to how McLean understood the relationship between manners and violence and how easy it was to shift from one to the other.

McLean has insisted that he is a sculptor and that all his activities stem from this discipline, whether it is a performance or a painting; as such he categorised Good Manners and Physical Violence as a ‘live action performance sculpture’.4

He also hoped that the audience would treat the performance like a sculpture, coming and going as they pleased, maybe standing for a while or circling the action. For him, the live action did not mean museum visitors had to alter their normal viewing habits. However, the majority of the audience remained for the full duration of the performance, many taking seats to watch from start to finish.5

Philomena Epps

April 2016