Since the 1980s political Blackness has faded into ethnic categorisations, accompanied by the emergence of state funds that are increasingly linked to crude racialised indices, giving rise to hierarchies of oppressions.1 These socio-political developments have shifted discussions away from issues of racism and racialisation, to tick-box exercises in diversity, despite performative discussions of intersectionality, creolisation and decolonisation within art historical and academic institutions.2 The present-day focus on ethnic descriptors is also inherent within funding strategies, archival methodologies, cataloguing standards and research ontologies on the British Black Arts movement.3 It is my assertion that political Blackness should not be understood only as a terminological descriptor that needs to be dismissed or overcome, for this mode of analysis fails to acknowledge that the archives of the British Black Arts movement were developed from forms of collectivisation that were shaped by a historical context and were ‘equally shaped by the kind of material collected, and the way it is arranged and described as well as by what is excluded from an alternative recording of history’.4

From independence to institutional capture

Encroaching gentrification of east London, inflated studio rents, the lack of stable long-term funding and a desire to maintain access to the Panchayat Collection underpinned the decision in 1997 for the collection to be relocated to the University of Westminster. There was hope that this move would preserve the Panchayat Collection for future generations, providing documentary evidence of the rich creative ecology of artists, writers, curators and producers of colour that made up the British Black Arts movement.5 Speaking personally, when the Panchayat Collection moved into the University of Westminster Library I had great expectations, and some assurance from the University of Westminster library staff there that the collection would continue to be utilised by the university’s research faculty and made accessible to students and by appointment to independent researchers.

Unfortunately, however, the collection was never embedded successfully within the university’s research culture, and access to students and other researchers was never fully realised.6 The University of Westminster Library catalogued the books and videos within the collection, but the majority of items – open source material collected by various individuals – remained uncatalogued.7 In late 2014, as part of the redevelopment of the University of Westminster Library, the senior management team wished to make arrangements for the relocation of the Panchayat Collection to an external site. After consultation with myself and Shaheen Merali, the library staff approached Maxine Miller, a librarian at Tate, to rehouse the Panchayat Collection within the Tate Library.8 Miller recognised that the Panchayat Collection would add value to the resurgent research and curatorial interest in the British Black Arts movement, and her understanding and history of working with the archives of the Black Arts movement played a key part in our agreeing to the transfer of the Panchayat Collection to Tate, with the hope that it would once again become accessible to researchers.9 The transfer took place in 2015 but, for a further five years, the collection remained largely uncatalogued and inaccessible to the artists whose work is present within the collection, its former custodians and researchers.10 This lack of access partly informed Miller’s development of a research proposal focused on the Panchayat Collection, which ultimately became Provisional Semantics: Addressing the Challenges of Representing Multiple Perspectives within an Evolving Digitised National Collection.11

Structures of collaboration

The importance of access to the Panchayat Collection, informed by my own experience, needs to be contextualised in relation to the cultural ecology of London in the late twentieth century, and my position within it. In the 1980s, within the British Black Arts movement, an emphasis on collaborative activity engendered the formation of collaborative modes of exhibition-making and the development of archival organisations centred on documenting the intense activity of politically Black artists. Collectives claimed the cultural space for politically Black artists by organising exhibitions, cultural interventions and critical debates. They challenged the dominant modernist discourses that had positioned Britain’s Black and Asian communities as a social problem, outside the discourses of modernity and modernism, and that had conceptualised the ideal artist as an isolated, white male, not impacted by the socio-economic sphere.12 In their 1987 essay ‘Piper & Rodney on Theory’, Keith Piper and Donald Rodney, founder members of the BLK Art Group, declared:

In Britain’s art schools, where the mythology of self-expression is held at a premium, collaborative activity is discouraged. Apart from throwing a spanner into bureaucratic machinery geared to assess the virtuoso, collaborative activities begin to counter many of the negative effects of individualism which leaves the art student isolated and vulnerable. Supporting collaborative activity has never been in the interests of art school hierarchy, as many students expressing an interest in working collaboratively learned to their cost.13

Collective activity was a key part of the UK’s alternative subcultures in the 1970s, which fostered the development of a vibrant movement that included ‘women and gay rights, food-co-ops, the Poster Collective, All London Squatters, film collectives, underground magazines’.14 Underpinning these collectives and collaborative modes of working was an explicit and sometimes implicit commitment to cultural democracy, coalition-building, access and recording of alternative histories. These collective ways of working also gave rise to Black and Brown communities facing racism and discrimination organising under the collective term ‘Black’ as a political identity and category and not an ethnic descriptor. These forms of collective organising were mirrored within Britain’s Black and Asian communities, for example with the formation of the Race Today Collective, Organisation of Women of African and Asian Descent (OWAAD), Southall Black Sisters and others.15 Importantly, the 1970s social housing co-ops would provide affordable, collaborative, accessible spaces for collective living for many Black and Asian artists and artists of colour in London after graduation in the 1980s, allowing many artists and cultural practitioners to develop and maintain a creative practice.16

I grew up in London and became active in anti-racist campaigns as a teenager, and by my mid-twenties I had gained considerable experience working with a number of collectives, ranging from multi-racial feminist groups, music and photography co-ops, Black feminist organisations and housing co-ops. These experiences also led to my involvement with Black filmmaking collectives. My personal history with this mode of working and collectivising foregrounded my subsequent involvement with the Panchayat Collection.

Janice Cheddie with the Panchayat Collection, University of Westminster, April 2015

Photo © Janice Cheddie

Curator Okwui Enwezor’s analysis of the 1980s art collectives, in his 2007 essay ‘Coalition Building’, makes a distinction between formal and informal collectives. Formal collectives, he argues, produced an authorial voice, an oeuvre that ‘designates the specificity of their practice and identification with a product, image, text, etc’.17 British examples from this period include the Black Audio Film, Retake and Sankofa Film collectives. Furthermore, formal collectives, on entering the art historical institution, can fit easily into pre-existing categories for the artist and the art historical canon. On the other hand, informal collectives, according to Enwezor, are entities that do not have a fixed membership and are instead comprised of a broad-based coalition ‘that galvanise[d] individual supporters around common interests, in order to affect and correct critical deficit in the political and social sphere … engag[ing] adherents and supporters across the political, economic and cultural classes’.18 1980s informal art collectives in the UK include Shocking Pink (magazine), Panchayat Collection, CopyArt Collective and the Brixton Artists Collective.19

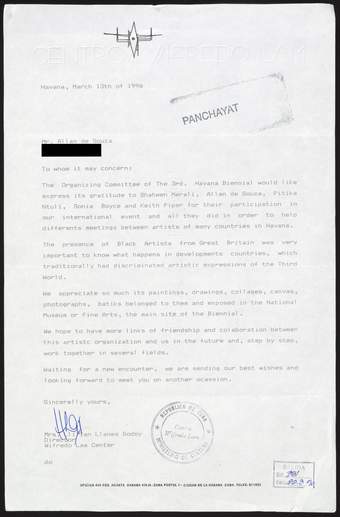

Letter of gratitude from Llilian Llanes Godoy, Director of the Centro Wifredo Lam and Artistic Director of the Third Havana Biennial, to artist Al-An deSouza (formerly Allan deSouza), 13 March 1990

Panchayat Collection, Tate Library 08133655

As an organisation, Panchayat produced texts, exhibitions and collected artists’ materials, exhibition documentation and other cultural interventions with authorial signatures, but this material only forms a small percentage of the collection. There are documents, books, artists’ ephemera donated by artists, curators and educators, or collected by members of Panchayat. A significant proportion of the material held within the collection is open-source and testifies to the innovative use of pre-internet age, low-cost technologies by artists who produced work with photocopiers, computers, video and tape-slide to form new modes of creativity and self-actualisation, leaving in their wake archival evidence of presence. This mode of production is evident in the work of politically Black artists including Rita Keegan, Allan de Souza, Chila Kumari Singh Burman, Donald Rodney, Black Audio Film Collective, Said Adrus and many others.20

While Panchayat’s collecting was focused on artists of colour within Britain and the Global South, and on forms of solidarity, it had a fluid structure and membership and did not have a formal written collecting remit.21 The lack of a collecting remit was also tied to the Panchayat Collection functioning as a working resource for artists, curators and researchers before its move to the University of Westminster Library. However, Tate has sought to locate the Panchayat Collection as a formal collective with its emphasis on the founder members, maintaining that Shaheen Merali and myself had little to contribute to the research and understanding of the collection, while simultaneously requesting our unpaid labour.22 This positioning of the Panchayat Collection as a formal collective has also been reflected within the Tate’s research and cataloguing methodology and its Collection Management System, a classification that demands closed contexts and authorial signatures that can be fitted into rigid, linear, chronological and racial groupings, which has led to the exclusion of a multiplicity of voices that contributed to the development and preservation of the collection.23 A key example is the neglect of Panchayat member Helen Oxford Coxall’s crucial role in the transfer of the collection to the University of Westminster in 1997.24

This exclusion of politically Black voices within Tate’s formal research processes was then mirrored within the Provisional Semantics research project. Provisional Semantics was initiated by Maxine Miller, a black Caribbean woman, but she was unable to participate in the realisation of the Provisional Semantics project. Despite this debt to the intellectual labour of a black women, and to the importance of Britain’s black intellectuals to the development of the British Black Arts Archives, at the heart of Provisional Semantics research initiative is a majority monocultural research team. The following passage is taken from the project’s interim report, published in 2020:

Provisional Semantics research team would like to acknowledge at the outset of this report the problematic makeup of the team – which at the time of writing, and despite the inclusion of two researchers who consider themselves to be people of colour and one who identifies as mixed race, is best described as majority white. The project was initially conceived by a black woman member of staff at Tate, but due to ill-health was not able to participate in developing the funding bid. The prospective project was subsequently taken up, with her permission, by white colleagues, and the initial, prospective project team comprised only white women until the above person of colour was brought in shortly before submission to the call.25

This report goes to state: ‘we acknowledge that the makeup of the team remains ethically problematic, and that we have taken no direct steps to alter it’. This is despite the multiple citations of the importance of Black Lives Matter global protests of 2020.26 This illustrates the writer Sara Ahmed’s assertion that ‘Such admissions are not anti-racist actions, and nor do they commit a state, institution or person to a form of action that we could describe as anti-racist’.27 In short, the research team did not feel that it needed to act to address the lack of Black scholarship within its own staff.28

The approach to researching the Panchayat Collection as part of Provisional Semantics stands in stark contrast to the epistemology developed by the Rita Keegan Archive Project (RKAP).29 A publicly funded project undertaken at the same time as the Provisional Semantics project, the Rita Keegan Archive Project can be positioned as a generous inter-generational and inter-racial collaboration led by the artist Rita Keegan and Black women archivists, the project provided an exemplary approach to the development of a rigorous, scholarly, inclusive research practice on the archives of the British Black Arts movement. The RKAP centred on the relationship between Keegan’s artistic practice and her archival work, while also placing at its heart Black scholarship, digitisation and cataloguing of the archive, ensuring equitable access for future researchers to an important archive on the British Black Arts movement.30 The contribution of Britain’s rich politically Black radical intellectual tradition remains an important part of developing the scholarship on the archives of the British Black Arts movement.31 Without a commitment to a nuanced understanding of political Blackness, modes of cross-racial solidarities, multiplicities of practice, and a critical assessment of existing library and archival classification mechanisms, contemporary research on the British Black Arts movement will replicate narratives of erasure and reductive concepts of race and racialisation.

The importance of access

Independent socially engaged art collections from the 1980s are now increasingly deposited in government-funded institutions, often filling gaps in formal collecting institutions or higher education institutions. The depositing of these archives has been an important step in saving many of these collections from loss, dispersion or destruction. However, once deposited, these collections are often not catalogued or made accessible due to lack of funds, but paradoxically are also increasingly subject to specialist, elite, publicly funded research projects. These privileged research initiatives often posit the collections as the raw material – a tabula rasa without a history or collecting ethos – on which funded researchers may impose new narratives and meanings. Reading through proposals for these research projects, beyond their theoretical questions of art historical investigation, collection management and/or archiving, there is often a lack of engagement with the fundamental principal of enabling and maintaining public access to these collections.32

Inherent to the informal collectivisation and collecting of these socially engaged art archives was the principle of cultural democracy. How is this principle of cultural democracy and access to be realised if the Panchayat Collection and other collections of often disenfranchised and marginalised artists are only open to a select few? It is only through enhancing and maintaining free access that we will be able to ensure the diversity of future researchers. In his analysis of archives, the philosopher Jacques Derrida asserts: ‘[T]he democratization can always be measured by this essential criterion: the participation in and the access to the archive, its constitution, and its interpretation’.33 Derrida’s conception of an archive posits what I believe to be an unanswered question: is there a link between the archive and concepts of social justice? If so, on what do we base this? For me, the answer to this question lies in the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights and its assertion that the right to take part in cultural life guarantees the right of everyone to access, participate in and enjoy culture, cultural heritage and cultural expressions

If we accept that the collections of politically Black British artists of the latter part of the twentieth century constitute the documentation of the creative cultural expression of the Black Arts Movement – a movement that is now recognised as having made an important contribution to the development of contemporary British art – then access to these collections is a human right.34 Based on the articulation of the human rights case for access to archives and collections, it therefore follows that the principle of free access should remain key to any discussions concerning the development and dissemination of these collections.35

The link between the Derridian notion of archival justice and the maintenance of digital access to documentary heritage is illustrated by the work of Arthur Torrington, secretary of the Equiano Society and the Windrush Foundation. In 2008 Torrington fought and won access to the digitised records of enslavement for the descendants of enslaved Africans by articulating that it forms part of a historical claim to reparatory justice.36 However, access to Britain’s other colonial histories, for researchers based outside the UK, remains inaccessible.37

Digital extraction

Since the financial crash in 2008, the UK and other Western nations have been in a period of prolonged economic crisis, the pressures of which have led to cuts to arts and culture programmes. Undoubtedly, the finances of UK cultural institutions will face further budget cuts and come under increasing pressure to monetise their creative, cultural and intellectual assets. It is within this fraught arena that digitising archival material brings not only the potential of increased access but, conversely, also the possibility of monetising the analogue and digital archive by placing access to historical material behind a paywall. Crucial to the concept of archival justice is access, enabled through the costly and time-consuming process of cataloguing. In the case of the Panchayat Collection at the Tate Library, this has meant securing an undertaking from Tate to catalogue the collection and to make that catalogue searchable and publicly accessible via an online portal.38 Cataloguing documentation and creating online catalogues are costly and time-consuming processes. This important work has only been made possible recently, through the support of Tate Library staff and volunteers.

With regard to historically racially diverse artists’ collections, a commitment to archival justice should come with an obligation to involve racially diverse artists and scholars within research into these collections. Without a commitment to enhancing and maintaining free access to the archives of the British Black Arts movement and recognising the importance of the development of inclusive inter-racial and inter-generational research processes, these collections will be increasingly limited to an increasingly narrow band of privileged, elite funded researchers and methodologies, thereby severing the link embedded within the formation of these collections and the principles of access, cultural democracy and social justice.